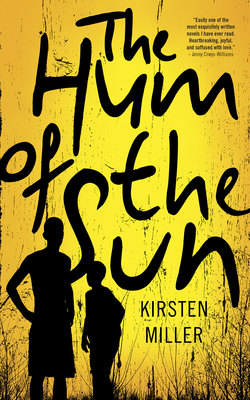

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2.

ОглавлениеThey followed the road that drew away from the town. Ash’s boots drummed a determined crunch on the gravel, repetitive, rhythmic steps that Zuko counted as he walked. The sound kept their pace, measuring the morning. Zuko focused on the footsteps. The distance between each step remained exact, emitting no sound as negative space, predictable and consistent. Footsteps, like stars and circles and a pattern of sticks and stones, had the potential to be infinite if something didn’t occur to stop them. There was the predictability of potential infinity. So reliable. Nothing other than what it was.

Ash carried the green bag on his back. The clouds in the sky held no such pattern nor predictability. Clouds tumbled like bedclothes with neither order nor purpose for themselves when the night was over. Ash’s free hand kept a firm grip on Zuko’s. Zuko understood it prevented his impulse to run back. It kept their motion forward, despite what his body might want. The craving was to watch the sharp pine needles fall from his hands for hours behind the house, or for some other activity that could satisfy his need for the whole space of potential infinity.

Zuko had no knowledge of what was in front of them. A pigeon chortled a hollow, hooting sound from deep within the base of its throat. Gravel crunched. Trees held the boys on a single track, guarding the road on either side. His bare feet were practised at navigating the endless small stones with ease. He counted them beneath his calloused soles. He matched his steps with Ash’s stride, but the rhythm fell out too soon because his legs were shorter, his feet more feeling, and he lost the balance between their movements. A quiet discomfort grew in his chest.

As the morning warmed, the sound of birds penetrated the air, stabbing-pitched tweets, unpredictable and random. He wrenched his hand from his brother’s and covered his ears to protect his brain. He heard Ash’s voice and his fast-talking, but the words were indecipherable. He had no idea what they meant.

A cold jab sliced through his foot. There was no pain. Instead a thick sensation of bile passed through his gut. He took his palms from his ears and shook his head. When it failed to work the first time, he kept up the motion that put the nausea in the background, and gave him something to focus on. Ash kept up the rhythmic crunch beside him, looking ahead. Where are we going? Zuko wanted to ask, but he had no words to say it with. Why have we left my mother in the ground? When will we go back?

Slowly the clouds melted from the sky, and left an endless hole of blue. The cold on the underside of his foot grew. He couldn’t look down. The sick feeling pulled him forward and he was afraid he would fall. Suddenly Ash grabbed hold of his hands.

“Zuko, your foot!” Ash yanked him onto the side of the road where soft tufts of grass grew together to create a resting place. He sat and took Zuko’s heel in his lap. The knapsack rustled. Ash extracted the water bottle from the bag and poured water over the wound to clean it. Then he put the bottle to his lips and drank in two guilty swallows. “Here,” he said, and handed the bottle over. “Have some. We’ll fill it up at the bend, before the road leaves the river.”

Zuko drank. The water seemed only to fuel the sick feeling inside him, to swell the sack of nausea that weighted his stomach and head. He stopped drinking. Ash took the bottle back and screwed on the lid. He leaned over Zuko’s foot. “There’s glass in here,” he said. “I’m going to pull it out with my nails. It’ll be sore. Hold on.”

Zuko’s brain isolated the word “sore”, and rolled it around in his mind. He tried to figure out what that was. He only knew his foot was cold and his head was thick and he couldn’t look at the cut or the blood that continued to seep from it, though Ash had tried to wash it away with the water. Something plucked his skin, like a string or a harp or a bow or a chicken’s feather. The cold intensified, and then faded. “We’ll find you a pair of boots,” Ash said. “You can’t go the whole way without proper shoes. And you’ll have to wear something on your feet when we get there.”

There remained a picture so clear it might have been a photograph in Zuko’s memory. It had been four years. Now he thought of the man smiling and the man not smiling. He thought of the man with his arm around his mother, and how the top of his head had looked when he’d held Zuko up high above him and bounced him in the air with giant hands. A searing ripped through Zuko as though it was sound. Ash’s elbow angled into him as he tore a shred of cloth from the bottom of his shirt, and bound Zuko’s foot with it. Zuko laughed into the air. If he squinted his eyes and held his head at a certain angle, his toes seemed to have separated from the rest of his body.