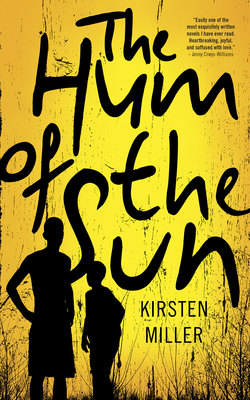

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4.

ОглавлениеThey wanted him to talk and they wanted him to do things that were too difficult for his body. They wanted his mind to go in directions not natural for him. He tried for their sake, he tried for his own, and in the end it was an enormous effort that resulted in one or two options: their exaggerated, embarrassing joy, or their futile disappointment. He failed to understand how one small person – him, Zuko, so insignificant in the history and trajectory of people both backwards and forwards – could have such power to make the people close to him happy, or disappointed. It wasn’t right that they should be affected by what he was able or unable to do. He felt the wind and the sun and saw the patterns in his head. Making sounds was hard. In the beginning, he’d tried only to see the light altering, one way or another, in his mother’s eyes. As he grew older, he became more wistful, less sure of the wisdom of others. Yanela began to demand less of him. Eventually she asked less that he be like her, or like his brother and sister. She spent more time with him, as she accepted who he was. Gradually, she found her joy in him, when she began to recognise his in himself. On the surface, it might have appeared that he was trapped in the idleness of his being. Underneath, though, he was quietly creating his own order. The Cheerios. The circles. The patterns reflecting a bigger existence that he couldn’t yet fathom. When someone stopped or interrupted him, he grew angry. He threw things down, broke things sometimes, because of the nature of the order he had imagined, but had yet to learn to understand.

Once he’d stood at the river with a tennis ball in his hand. His fingers flitted across its furry skin, tracing the circumference of the perfect circle. This is how he learned that there was no beginning and no end. The trees whispered a similar story around him. He learned what mattered with his heart. “See those children?” his mother said. “You need to learn to play with them. Take that ball, and go and throw it with them.” That was when she’d been full of directions. She hadn’t seen him yet; exactly who he was. It took her a long time to catch up with what his body knew and understood. “Go and swim with your brother and sister. It’s such a beautiful day.” These were the kinds of things she’d said to him. But the pain of imagining how his body would have to move in order to take off his shirt was too much for him.

At first she waited for his words to come. It was for him, of course, but also for her. She wanted, for him, the life she’d imagined. Something easier than this, where conversations flowed like ideas and movements, as naturally as the tidal river. She’d wanted him to talk because it was the way of the world, the way of people, the way of parents and children. She hadn’t yet seen it was a way not meant for him. And because he had no words, he could not engage in the backwards and forwards of polite conversation between adults and the verbal skirmishes of children, nor the endless human banter about who was right and who was wrong, the rules people followed, who was first and who was last, the dominance and the submission. Instead, he engaged himself with other things. He spent hours examining the way the tops of the pine trees moved in the wind. He watched the colours of sunset, how slowly they changed in the evening sky. He studied the texture of soft ground, the crunch of gravel on long walks. He observed the patterns of the river as they changed with the light of morning, noon and evening, or with the moon’s pull, and back again. He learned the sounds of different birds, and imagined them in association with different states of being. Some birds were light and optimistic. Some called mournfully, as though they would never be happy again.

While his mother stayed busy with her house tasks inside, sweeping the floor with the broom made of a branch, washing the walls, or making the house neat, he’d cry to go outside. “No, Zuko!” she’d say. “I’m busy. There’s no time now.” He’d moan and wail and wonder at the emotion inside himself; how he could feel so enthusiastic, and then so desperate. Such extremes in such a short time, and over the same thing.

He learned, eventually, to take his cues from her eyes. When she was happy with him, he noticed the peace there – the approval, when what he did was right. He learnt the other side also – that he could displease her. He alone was capable at times of causing an ancient deadness in her eyes. Zuko came to understand that no one person was ever enough to make another completely happy.