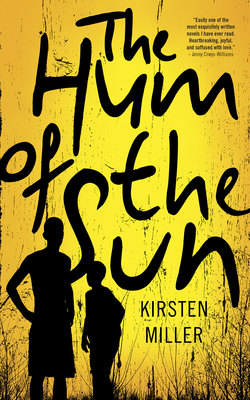

Читать книгу The Hum of the Sun - Kirsten Miller - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2.

ОглавлениеThis is what Ash remembered. The whitewash of the cold wall. Summer nights too hot to sleep. Insects crawling the breadth of the pillow. The noises that came when the stranger stayed over. Her sighs, his groans.

From the shadowed space on the other side of the wall, Ash thought that they were only exercising, late at night. He’d seen older boys on the mapped-out field beyond the settlement of river houses. Young men who worked their bodies, shaping their torsos into the kind of flesh that youth bestowed and took for granted. The goal posts were imagined, drawn onto the ground with chalky paint that washed away in the summer rains. The way they pushed themselves up from the stubbed grass with bulked muscle arms, their legs prostrate at a forty-five-degree angle, dark skin glistening, eyes focused and hard. When he was eight, Ash longed to be like them, sweating and pushing and striving towards a goal, each exercise session a feat of physical perfection. At night, he lay wide-eyed in the dark, listening to his mother and this stranger from the city. He mapped their movements in his mind as he imagined how they perfected their push-ups, turning over with the bedsprings, marking time like a metronome. He didn’t know that to each other, their bodies were already perfect. He didn’t know that the strides they made towards a greater fitness were incidental. In the summer weeks that year, when he swam for hours in the brackish river water and baked like a fish on the dry bank, the stranger and his mother had made each other happy. They had, in addition and inadvertently, also made his brother, Zuko.

After Zuko was born, the stranger stayed around more often. They played together like a family beside the river with a ball the stranger had brought for the smallest boy. At first, when the child began to walk, the stranger coaxed Zuko to kick the ball. Zuko tried. Gradually, though, he seemed to lose interest. Gliding white clouds distracted him too often. He frequently looked away from the ball at a passing bird, or a shadow that hovered like an egret across the lawn.

“What do I call him, Ma?” Ash asked Yanela.

“Who?”

“The man who comes here.”

“Call him what you like.”

Ash had thought she might insist on him calling the stranger “Baba” or “Pa”. He looked at his mother as she hung washing in the front of the house. His sister, Honey, played inside with a rag doll, and Zuko skirted between the hanging sheets at their mother’s feet.

The man was an outsider in their lives; any word that meant “father” felt too familiar.

“What do you call him?” he asked.

His mother took a peg from her mouth and used it to secure a small T-shirt in the wind. “Dom. Or Dominic. I like the whole of his name.”

“What does he call you?”

She cast him a fleeting glance. “Yanela,” she said. “Sometimes other things as well.”

“If he was a real father he’d be here all the time. He’d live with us.”

“That’s not true. Lots of real fathers don’t live with their children.”

“Did your father live with you?”

“Yes. I wish you’d known him, Ash.”

“Why?”

“Because I loved him very much.”

“What happened to him?”

“A car hit him one night, on the main road. After that I didn’t have a real father any more. And since then, there has always been something missing.” She picked up the empty washing basket and took it inside. Zuko followed silently on small bandy strides behind her.

In the kitchen, Ash helped her stack the dishes from the rack onto the shelf. “What are we, Ma?” he asked her.

“What do you mean?”

“What kind of people are we? Are we brown people? Or black people?”

“Look at your own skin, Ash,” she told him. “And decide for yourself.”

“I’m darker than Zuko,” he said. “And darker than Honey. But we speak everybody’s languages.”

“We’re everything, Ash,” she told him. “We’ve got different people in us. Our ancestors came from both sides of the sea. But you were born here. I was born here. Your grandfather was born on this farm when it was a working farm. He had calloused hands from working. We’re African, Ash. Don’t let anyone tell you anything else.”

“Is he African?” Ash asked.

His mother glanced at him. “Who?”

“The stranger.”

Yanela’s arm rested briefly on the sink. Her eyes fluttered to the light, long enough for Ash to know that the thought was new to her. “I don’t know,” she said softly. “I don’t know if he completely understands.”

“Understands what?”

She dragged a rag across the sink in a final attempt at keeping order. “The history that is the air that you and I will always breathe.”

The year Ash turned twelve the stranger came and went for the last time in the final week of summer. Each day their mother rose early, fed Zuko and Honey, and left the house. She stood at the edge of the road and waited for the Hilux with the surfboard strapped to the roof to stop and pick her up and take her to the big house that fronted the river at the bend. She stayed away all day. When she returned in the evenings, her face glowed. She kissed Zuko and held him to her like he was still an infant needing the warmth of her breast.

“He’s not a baby, Ma,” Ash told her. “He’s already four.”

She sighed and wiped the moisture from her brow. “I know. But then . . .” She kissed Zuko’s head. “All of you will always be babies to me.”

“Why do you like him?”

“Because he’s my child.”

“No, I mean that man. That stranger.” Dominic. The name stuck, heavy and clumsy at his lips.

“A man needs a woman, Ash. One day you’ll know what I’m talking about.”

“Do you need him?”

She smiled at her son. “I don’t need anything. Apart from food. And my children. This world is a free place, Ash. Don’t be tied up with anyone else’s ideas for you.”

The stranger parked his vehicle outside the house in the evenings. He sat with Yanela on the couch in front of the portable television set, his hand high on her thigh. Sometimes he leaned in and kissed her neck. Ash cooked the meat they brought home on the gas stove and served it to them cut into thin strips, the way the stranger liked it.

“Thank you, son,” the stranger said. His teeth gleamed white behind his pink lips.

“Why does he call me son?” Ash asked later. Yanela chopped wood on a dry stump outside. She glanced at him, and shook her head, but she didn’t answer.

“Why is my name Ash?”

She leaned in and put a finger under his chin as though plucking the string of a musical instrument. “You’re what’s left of a fire that burned out a long time ago,” she told him.

Deep into December, more cars arrived at the house on the river’s bend. The stranger no longer fetched Yanela in the mornings. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, she put on a headscarf and walked the distance to make beds and wash dishes and peel the vegetables that the stranger and his family would have with their roasts and braaied meat at night. Sometimes he brought Yanela home early in the Hilux, the surfboard a sturdy identity strapped to the roof. They went into the bedroom and locked the door, emerging only an hour later. The stranger stood outside in a pair of shorts, humming and soaping himself from the bucket of cold water Ash fetched from the communal tap every morning.

“Where does he live?” Ash asked his mother.

“In the city.”

“Is he rich?”

“I suppose so.”

“Will you marry him?”

She laughed, and snapped the shirt she held in her hand. Reaching up, she secured it to the line above her head to dry. After that, she seemed to lose herself in her own head.

Ash knew that the stranger came with the summer, and made his way home when the season was over. Ash knew too, without being told, that the stranger was how his brother was able to eat Cheerios for breakfast every morning, how his mother afforded a new dress each year, and how there were always slabs of steak in the kitchen whenever he was in town. Zuko never ate the meat the stranger brought. If his mother offered it up to his mouth, the little boy pressed his lips together and glanced at her as if to ask, why do you make me eat such a disgusting thing? The child whimpered, and looked away.

The last evening the stranger ever visited the house, Yanela was upset when they arrived through the door. Without acknowledging her children, she went through the kitchen and into her bedroom. The stranger barely kept pace behind her on his long legs, his mouth set tight, his eyes dark and not seeing the children. He followed her into the room and shut the bedroom door behind them. All evening, Ash entertained his brother and sister while the adults spoke in strained whispers in the next room. Suppertime came and went and the small children whined. Ash cooked mealie meal for himself and his sister, and he put out the box of Cheerios for Zuko. They ate quietly together at the table, while the adults argued.

When darkness wrapped the house, the bedroom door burst open. The stranger emerged, filling the doorway. He spilled into the kitchen, and moved through into the open outside. The door of the truck’s cab snapped open, and Honey and Zuko ran outside after him. Yanela came to the doorway and called out, “Dominic!” The man paused and turned his head but she remained in the doorway, frozen. For a moment, the stranger seemed about to return to her, but seconds later he left the car and the path, and went to the nearby tree where Zuko now lay on his side, pulling up grass strands from the earth by their roots. The man stood, his fists closed at his hips, gazing down at the boy. Zuko barely raised his beautiful eyes at the attention. His hands pulled and released, pulled and released, a motion that might go on until Ash fetched him to finish his supper. The stranger squatted and said something softly, inaudibly, to the boy. Ash, his sister and his mother watched. The stranger kissed the child quickly on his head, and returned to the vehicle. Without a glance backwards, he pulled himself into the cab and slammed the door, revved the engine and reversed the vehicle before he turned it onto the gravel road.

Later, Ash drifted into sleep with the sounds of his mother softly sobbing. It was the last time the stranger came to the house. Never again did Ash hear his mother cry.