Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLittle Brown Brother on the Rise

2

SUSAN F. QUIMPO, NORMAN F. QUIMPO, AND EMILIE MAE Q. WICKETT

Manila, August 16, 1968 – The police fired in the air tonight to disperse about 300 students who stormed a police cordon around the United States Embassy here.

The students were protesting special United States-Philippine relations that they said led to such incidents as the killing of Filipinos on American military bases.

The warning shots were fired when the students threw lighted torches into a police line guarding the Embassy gates. A student charge was then broken up and several demonstrators were arrested.

The New York Times

(Susan)

THE MOOD HAD not always been so embittered. Only a generation ago, the Filipinos held Americans in esteem—as benevolent colonial masters, as mentors of democracy, as allies in a bitter world war. But in 1942, when the Japanese encroachment of the islands was inevitable, the Americans readily abandoned their colony, choosing to defend Europe instead. Left clinging to Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s cryptic promise, “I shall return,” the Filipinos continued to resist Japanese military occupation for the next three years.

If World War II had been a final test meant to measure the assimilation of lessons on textbook democracy and patriotism espoused by the Americans, the Filipinos would have painfully garnered the highest scores. America’s “little brown brothers,” as the colonizers had called them, proved their loyalty to the American flag, surpassing all expectations. As proof of their valor, thousands of Filipinos died in the war; many were heavily tortured as they continued to protect American civilians. The stories of many young women raped or kidnapped to fill brothels for the Japanese soldiers echoed through the towns and cities.

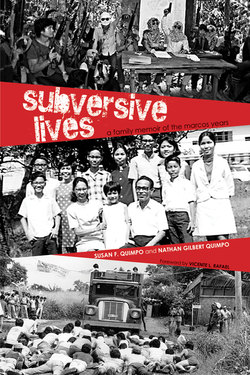

In the late 1960s, most of the family still lived in Manila. Esperanza Ferrer Quimpo (Mom) and Ishmael (Dad) are seated. In the front row are (from left) Ryan, Susan, Jun, and Caren. In the back row are Jan, Emilie, Nathan, Lillian, and Norman and his wife Bernie. Lys and her husband had already left for the U.S.

And MacArthur did return, to hold true to his messianic promise to the Filipino people and to rescue an ego bruised by the Japanese who had defeated him on the battlefield. The poor Filipinos welcomed his return, not realizing that if the alternate American strategy, which was to take the shorter route to Japan, had prevailed over MacArthur’s bypass operation in the Philippines, the Japanese forces in the country would have withered on the vine as in other islands in the Pacific left alone by the Americans, and the country would have been spared the horrors of 1945. As it was, the Americans drove straight to Manila to save their kin held in an internment camp in the heart of the capital, directly confronting the Japanese naval forces assigned to defend the city. The resulting battle gave Manila the distinction of being the only other captive city besides Warsaw that was fought over and completely devastated at the war’s end. Manila, the Pearl of the Orient of prewar days, with an old-world charm but displaying the best of American modern urban planning, became the worst-looking city of the postwar period. All the stately edifices of the Americans were wrecked together with the quaint Spanish city at the heart of the capital. Truly, what the Americans had given, the Americans had taken away by that act called “Liberation.”

(Norman)

MY PARENTS PROBABLY never understood why activists, and we brothers in the revolutionary movement, were so hard on the Americans. We didn’t have the direct experience of living under American rule. They did, and what they saw they admired. They must have winced every time they heard the Americans blamed for the ills of the country. Their experience was the opposite. Ever since “independence,” the Filipino politicians who had taken over running the government had made a mess of the country. Mom and Dad longed for a return to the prewar days.

Both our parents enjoyed “Peacetime,” that is, the colonial rule of the Americans in the pacified Philippines. Having grown up after the period of the Philippine-American War, they had limited awareness of the various peasant rebellions against continued landlord and American rule. Never mind that the new colonizers systematized the exploitation of the country’s natural resources and took over control of Philippine business. The natives enjoyed universal public education and American ways, and Filipinos with initiative and/or talent saw that they had a chance to advance their status through education and hard work.

Dad studied in the well-established public school system and was enrolled in the American-founded University of the Philippines (UP) just before the war broke out. Mom, who came from a well-to-do family, did formal studies in music as a colegiala1 in St. Scholastica’s College which was established in the first decade of American rule. She would spend her summers in the resort city of Baguio, at the Zigzag Hotel which was owned by her uncle, a colonel of the Philippine Scouts.

Ishmael de los Reyes Quimpo (Dad) went through the public school system, enrolled for mechanical engineering just before the Pacific war and finished his degree shortly after the war.

The horrible experience of Filipinos under the Japanese occupation made Filipinos of all stripes genuinely welcome the return of the Americans. Mom and Dad’s experience with “Liberation” really drew them close to the Americans as a people because they got to know one particular American very well.

One of our “liberators” from the Japanese who landed with the forces in Lingayen and came to Mabini, my mother’s hometown, was a GI named Norman Katz. Katz was not your typical working-class or farm-bred GI. He was the scion of a Texas oil family. One of the things I remember Dad telling us kids was that on Katz’s birthday, a plane flew over Mabini and dropped a birthday cake by parachute.

There is a picture of a smiling Norman Katz in a squatting pose with my father and other cockfighting aficionados, fighting cock in hand.

When I was born in December 1945, guess what name my parents chose for me?

They gave me the impression that Katz spent some time in Mabini and became close to them. When the American forces suddenly got orders to leave Lingayen and move inland, Katz sent a note to Dad to get the stuff he would leave behind on Lingayen beach. Dad got the message late and had to be satisfied with the few hand tools and bric-a-brac others who had come earlier had not managed to drag away. I remember that as late as 1964, we still had Katz’s giant toolbox, open wrenches, and other massive tools that he had bequeathed to Dad in Lingayen.

Katz was to the family just a pleasant memory of the war until one day Dad received a package from his old friend. The family was happy to get a box of PX goodies from Katz, who had changed his name to Cass which, my father explained, sounded less Germanic.

(Emilie)

FOR ABOUT THREE or four years in a row, at Christmas time, we would get a box of American goodies—toys, long-playing records of popular children’s songs finished off in vinyl plastic, cookies, and candies. I think I was about six or eight years old at the time.

I asked Mom where they came from and she said they were from Norman Katz, an American friend who used to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces in Mabini. She told me that a group of American GIs used to call her “Hope” (the English translation of her name, Esperanza), and would direct admiring wolf whistles at her. She told them she already was committed (to Dad) and they didn’t have a chance.

I asked Mom if Katz’s daughter could be my pen friend, and she encouraged me to send my first letter. I distinctly remember being very excited when I got a reply (pity I can’t remember the daughter’s name now) in an envelope with American stamps on it. In her letter, Katz’s daughter told me about her pet hamster and how she cared for it. I did not know what a hamster was, so I consulted our set of Grolier’s Encyclopedia. We corresponded for a year or two, and then the correspondence dwindled. Mom also lost contact with Katz, and the Christmas boxes no longer arrived.

Years later, I borrowed several magazines from the USIS library on Padre Faura Street, which later became the Thomas Jefferson Library, where Mom introduced us to a library for the first time. I was always partial to Life magazine, but I also borrowed copies of Time for Dad every time I visited that library. In this particular instance, about two years after the Christmas boxes stopped arriving, I happened to read Time’s “Milestones” column. It had a small write-up about the death of multimillionaire Jewish businessman and philanthropist Norman Katz. I showed it to Mom and she said, “So that is why we haven’t heard from him for some time.” She added that she never knew he had become a multimillionaire.

I wrote a letter of sympathy to my former pen pal at her old address, but I never got a reply.

(Susan)

AFTER NEARLY HALF a century, America ended its colonization of the Philippine islands. Despite the much-heralded granting of independence in 1946, the reality of freedom was another matter altogether. The capital city was in ruins and the infrastructure set up during the U.S. colonial administration—roads, bridges, railways, ports, land and sea transport—in a shambles. Less visible were the almost mortal blows to the civil service organization and the public educational system. The Filipinos hoped that postwar aid and Japanese reparations would restore the personal wealth many had lost, as well as the modernization introduced by the Americans. There would be compensation, the Filipinos thought, for their suffering and loyalty to the United States. But the actual compensation the United States awarded to its loyal ally amounted to only half the total of the latter’s war damage claims and was grossly inadequate to rebuild the nation. And corrupt politicians stole and frittered away Japanese reparation funds.

Moreover, taking advantage of the fact that the Filipinos were in no position to negotiate, the United States refused to release aid to the newly-installed Philippine government until the latter agreed to a number of unequal trade treaties. These treaties allowed the unlimited importation of American goods free of tariffs, gave American entrepreneurs equal rights in exploiting all Philippine natural resources, and granted any American the right to own and operate public utilities in the former colony. Sen. Millard Tydings of Maryland had aptly described the parity rights to Philippine resources as a philosophy “to keep the Philippines economically even though we lose them politically.” And to safeguard its economic interests in the region, the U.S. government ensured American presence in the islands by installing military bases over which it maintained complete sovereignty.

The Philippine government conceded. The new nation’s first President, typical of the country’s ruling elite, only sang America’s praises. “In the hearts and minds of Filipinos, the stars and stripes flies more triumphantly than ever before,” he said in his inaugural speech. The new republic’s leaders were only too willing to agree to the unequal treaties because they were the first to profit from the trade of agricultural crops harvested from their own haciendas.

If in 1946 the majority of Filipinos regarded the Americans as benevolent masters, yearning for the good old prewar days, and nursed a dream to immigrate to America, many in the next generation had begun to question America’s continued influence. By the mid-1960s, the questionable trade treaties were christened with a new name: American imperialism. The bureaucrats and politicians of the incumbent president, Ferdinand Marcos, eager to serve the interests of the U.S. and cash in on their positions of influence, were later described by the radical writer Jose Maria Sison as “bureaucrat capitalists.” By the 1960s, students at the University of the Philippines (UP) and a few other schools began to examine the work of nationalist leaders, re-read history, and with renewed passion linked the country’s economic woes to the government’s continued subservience to the U.S.

Jose Quimpo and Maria de los Reyes had 13 children. Ishmael, top left, was the eldest son. Jose had four other children by a second wife.

When the U.S. began using its military bases in the Philippines as a springboard in its involvement in the Vietnam War, student radicals from UP and Lyceum of the Philippines began to target the outward symbol of American presence. “Embassy, Embassy!” the students chanted as they repeatedly marched toward the U.S. Embassy on the boulevard along Manila Bay. Soda pop bottles, stones, and Molotov cocktails became the students’ weapons to “reclaim” Philippine sovereignty from within the embassy gates.

Adding fodder to the fires of protest were the reports of an increasing number of “accidental slayings” of Filipino scavengers who frequented the garbage dumps outside the U.S. military base. An eighteen-year-old boy was shot and killed by an American marine who claimed the lad was “stealing a bicycle.” A Filipino laborer was shot and killed in broad daylight after a U.S. Navy officer mistook him for a “wild boar.” In each case, the American servicemen in question were acquitted by a U.S. Navy court-martial and quietly returned to the United States. All told, from 1947 to 1969, there were at least 30 such documented incidents.

From Manila’s maze of city streets, the students carved out their battlefields: the U.S. Embassy, the Congress Building on Arroceros Street, and Malacañang. As the 1960s ended, student demonstrations had become almost a daily occurrence. If classes at the universities were not suspended by President Marcos himself using the most trivial excuses, the boycott of classes by both students and sympathetic faculty members was common. Lessons from the “parliament of the streets” were considered of irreplaceable value.

“Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” echoed the Filipino activists protesting the state visit of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1966. “McNamara – Murderer!” read a placard. “Aggression, thy name is Johnson,” read another.2 The young Filipino nationalists were strongly sympathetic to Vietnam, which was viewed as an underdog defending itself from a would-be colonizer. That the Marcos government had willingly recruited Filipinos as technical support staff for America’s aggression against Vietnam was construed as further proof of Marcos’s allegiance to the U.S. In the halls of the Philippine Congress, assemblymen even considered the enactment of “a law sanctioning the participation of Filipino combatants (in the Vietnam War) under the American flag.”

The 1970s was to be a decade of change. A never-before-experienced fury of mass demonstrations led by students engulfed Manila. This outpouring of protesters that confronted the state’s forces, and a number of their countrymen’s long-held beliefs, in a prolonged political upheaval during the first three months of 1970, came to be known as the First Quarter Storm.

I WAS NINE in 1970. Then, my personal angst had to do only with my lack of athletic interests and the subsequent inability to skip rope, ride a bike, and master the more intricate maneuvers of a game of jackstones. My concerns, like those of the rest of my family, were soon to change.

When I was five, my family moved to 1783-H Concepción Aguila Street—a cramped two-bedroom apartment meant for four. We were a burgeoning family of 12! Only when I was 11 or 12, and some of my older siblings had moved out, did I finally get my own bed. “1783-H”—the “H” meant ours was the eighth and last apartment in a row of what today would be considered low-end townhouses. Firewalls blocked us from neighboring apartment complexes; the sole entrance and exit to our row of apartments was a narrow driveway that linked the eight apartments. The driveway was so narrow that anyone who parked his car at the end of it would have to wait until all other parked cars behind him had backed out into the main road to finally maneuver his way out.

As the youngest, I really didn’t mind the cramped quarters. Besides, at that age, my opinions did not matter. I was a mere observer who was quite invisible to everyone’s eyes. I was in awe of my siblings, and at an early age was somehow convinced they were all doing very important work. At the end of each school year, they would come home with little boxes lined with soft velvet that cradled medals for academic excellence. Once, when Mom wasn’t looking, I pulled out the carton of medals she hid atop the clothes cabinet and counted 72 medals for my brother Nathan alone. I garnered no medals in school and was quite content with the few little cards I got that said “honorable mention.” It really didn’t matter. In secret, I was fiercely proud of my siblings, and in my eyes they could do no wrong.

Like the time they literally jazzed up the 11 o’clock Catholic Mass at San Beda Church. The entire community called it the “Jazz Mass” because, instead of the regular repertoire of priestly hymns, my siblings Nathan, Jan, Ryan, and Lillian and some of their high school peers played popular tunes while expertly strumming guitars.

Attendance at the 11 o’clock Mass was at an all-time high, and many attributed this to their singing. My brothers had served as altar boys at this same church, and at its adjoining school for boys, they had stellar academic records. The Benedictine monks of San Beda were proud of the Quimpo boys. Nathan and Jan consistently had high grades, and Ryan almost single-handedly handled the school’s student publications. And as good Catholic boys, they organized the Jazz Mass every Sunday.

I don’t quite remember when things started to change. But even then their selection of songs for the Jazz Mass signaled the coming of the storm. The family would spend Sunday afternoons visiting my eldest brother, Norman, and his wife Bernie, in their apartment on K-10 Street, near Kamias in Quezon City. Norman would play his double record album of songs by Peter, Paul and Mary, and we would all sing along loudly. This was one way to learn of the Vietnam War and the rising protest against wars of imperialism.

Because all men are brothers

Wherever men may be

One union shall unite us

Forever proud and free

No tyrant shall defeat us

No nation strike us down

All men who toil shall free us

The whole wide world around 3

As my siblings began to shift to singing antiwar protest songs at the 11 o’clock Mass in San Beda Church, the streets around Malacañang, including ours, were quickly becoming a battleground. When did the battles for the use of our single bathroom shift to battles over ideology and class struggle? The storm was brewing outside the safe confines of our family life.

As student protesters filled the streets outside Malacañang, various forms of the government’s militia would be used against them. The students, armed only with rocks, soda pop bottles, and homemade bombs fashioned from leftover firecrackers or bits of gun powder, were no match for the government’s militia. The city police, the constabulary, the antiriot squads, the dreaded Metrocom, the presidential guards, the army, the navy, and even the city firefighters were sent to quell dissent.

With increasing frequency, our narrow driveway would be filled with student protesters desperately seeking to escape bashing by police truncheons. Our neighbors would swing open the red gate at the end of our shared driveway to welcome the students, then immediately bar it shut before the cops could follow. My mother, with the other sympathetic mothers from our little apartment complex, would then offer “the poor students” a bit of food and water before they returned to do battle with the police on Concepción Aguila, Mendiola, and J.P. Laurel Streets.

In a couple of years, the narrow driveway of 1783-H and the firewalls that blocked all other exit points would become a great concern. It wasn’t long before we would stare at those walls, wondering if my siblings were strong and swift enough to scale them in the event of a police raid. Our cramped two-bedroom apartment had to be “protected.” Spaces in the ceilings, crevices between windows and walls, even the toilet’s water tank, were inspected as possible hiding places for “subversive materials” and eventually a handgun. Ryan later installed outside our bedroom window a rearview mirror from an old car. The mirror was at an angle to reflect the image of the long, narrow driveway and the old red gate. Ryan said we could use the mirror to see if the police or the military was coming into the compound and to buy a few seconds to scamper for safety.

Modesto Ferrer and Presentacion Evangelista had three daughters named after the virtues: from left, Caridad, Fe, and Esperanza. They also had one son. Presentacion had four other children by her first husband.

1783-H Concepcion Aguila became a garrison, and in it we braced ourselves for the storm.

NOTES

1 A student of an exclusive school for girls.

2 From Jose F. Lacaba’s Days of Disquiet, Nights of Rage, Asphopel Books, 1982.

3 “Because All Men are Brothers,” music from Bach, lyrics from Glazer, was adapted and popularized by the folk singing group Peter, Paul and Mary in the 1960s.