Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

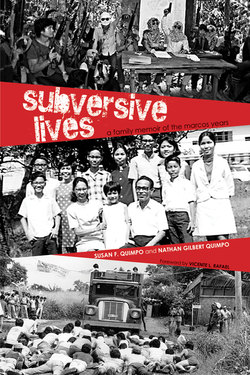

ОглавлениеThe First Activist in the Family

4

NORMAN F. QUIMPO

I REMEMBER MY BROTHER JAN best from his late high school and early college days. Jan (Ronald to people outside the family) came to live with my wife, Bernardita (Bernie) Azurin, and me in our Albany Street apartment in Quezon City’s Cubao district. He had just dropped out of school to become a full-time activist and had nowhere else to go. Strangely enough, the events that made Jan decide to leave school were the same ones that had led us to move to that apartment.

UP students barricade the main road to the campus at the start of the Diliman Commune, February 1971. (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

Bernie and I were married in 1968 and spent the first two years of our married life on a side road off Kamias Street, also in Quezon City. Number 101-A, K-10 Street, was perfect for a newly married couple. The neighborhood was quiet, the apartment was new, with two bedrooms nicely paneled with narra, and it cost us only P150 a month. I had my first job (and, as it would turn out, my last because I would never move) teaching mathematics at Ateneo de Manila University, which earned me a monthly salary of P450. Bernie was working at Tri-Media News (the cluster made up of dzHP radio, Channel 13 TV, and the Philippines Herald newspaper) and earning more than P300 a month. For us, those were fabulous sums. After setting aside money for monthly expenses, we still had a tidy amount left over. The cozy Kamias apartment was the symbol of a secure beginning to our married life. So why did we abandon that apartment for a walled-in though larger dwelling in a busy city center?

We moved out of our Kamias apartment in 1970. That fateful year, our hopes for a prosperous future began to look like escapist fantasies. Marcos’s reelection and the explosion of student demonstrations conjured up a picture of Philippine society as a social volcano about to explode. We could not situate our earlier middle-class dreams in such a dark landscape.

The feeling of living in a nice new apartment was gone too. Typhoon Yoling had blown away the roof of our landlord’s house which, though separate from our apartment building, felt like it was a part of it. There was no escaping the feeling of violation, as when a valuable item you’ve grown to treasure is damaged.

We finally decided to move because of oil price hikes in 1970. The resulting rise in the cost of transportation and consumer goods shocked people. Youth and labor organizations lent their strength to the transport groups that launched strikes. The strikes engendered a feeling of paralysis in the city. Some people felt stranded in their own homes. The neighborhood whose quiet we had previously valued now felt isolated, far from food stores and offices. We needed a place near Ateneo that was also close to a wet market and stores. We were relieved to find an apartment a few blocks from the center of Cubao, from which Ateneo was a short jeepney ride away.

MY MEMORY OF JAN goes back to a family picture taken in Iloilo. He appears as a sweet, well-behaved boy with a charming smile, which was what he was to me. Entering grade school in San Beda College, he was still mild-mannered and kind-hearted and could be the apple of any mother’s eye. But to his brothers and sisters, he also showed another side. Lillian recalls that the Jan she knew in Second Street showed a stubborn and rebellious streak and had his share of fights with his siblings.

Jan graduated from grade school in San Beda College at age 12 (1968).

In 1967, Dad and Mom were very proud parents when Jan was awarded a scholarship to the Philippine Science High School (PSHS). He was just 13 then. PSHS was highly regarded as a school that educated the cream of Philippine youth destined for careers in science and technology. The best part of it was that students got free tuition and board and lodging as well as a stipend. I rode with Dad and Mom in our Ensign sedan when they took Jan’s clothes and bedding to PSHS in the old wooden Philippine Government Employees Association (PGEA) quarters on Elliptical Road, the big rotunda circling the Quezon Monument in Quezon City. The same building housed both the classrooms and the dormitory. It was rare to see Mom so pleased and happy.

Later, my parents and I would learn about the rundown condition of the dorm and the perennial lateness of the students’ monthly stipends. The PSHS scholars may have been held up as the hope of the Motherland in science and technology, but they were subjected to the same bureaucratic foul-ups as other sectors of Philippine society. Jan often complained to Nathan that the students, all state scholars, had to put up with an ill-equipped and vermin-infested school and living quarters.

Earlier generations of students might have shrugged and silently put up with the sordid classrooms and substandard living conditions. Previously, Jan and his friends had looked forward with anticipation to the planned transfer of the school to a new site in the North Triangle area. Over two years, the students signed petitions, marched on Congress, and boycotted classes, all to no avail. Jan mentioned at one point that some students seriously considered burning down the building, which they said was a fire hazard anyway.

Jan (left), with a schoolmate, Joel Navarro, stands in front of Philippine Science High School, which was still in its old building at the Quezon Memorial Circle (1969).

They were primed to be involved in the outbreak of student demonstrations against the Marcos government. In the late 1960s, they joined a majority of Filipino students who, like other youth in Europe and the Americas, found the voice to air broad grievances, from prevailing injustices in world affairs, of which the Vietnam War was the glaring example, to the poor state of the educational system. Students expressed their disgust with the small share of education in the national budget, the mishandling of these limited funds, the high cost of private education, the poor quality of schools, as well as with the situation prevailing in the larger society. The widespread corruption in government and the failing economy directly affected them. They shared the daily struggle of their families to keep up with the rising cost of living and despaired at the dismal prospects for employment after graduation.

The head of PSHS was a well-meaning but essentially powerless government functionary who did not control the funds or have the political support to run what should have been an elite high school. She took the student protests as an attack on her personal leadership and did not see that they were part of an irresistible social movement. Like other school heads at the time, and like many government officials, business leaders, and parents, she did not comprehend that the student protests went beyond the usual teenage restlessness. Very few of the older generation were educationally equipped or temperamentally prepared to view the school strikes within a larger perspective.

When the massive student protests in Metro Manila against the Marcos government reached their peak in 1970, Jan and many other PSHS students were among those who joined the rallies. A number of PSHS student leaders forged alliances with leftist student groups, particularly Kabataang Makabayan (KM) or Patriotic Youth at nearby UP, as the premier state university was also the hotbed of radical student activism.

The author Ceres Alabado used the student activist group that Jan and his schoolmates organized in PSHS, the Malayang Kilusan ng Kabataan (MKK) or Free Youth Movement, as the basis for her novel, I See Red in a Circle. She liked being with these talented science students and acted as a surrogate aunt to them. They used to hang out in her house and talk about recent developments, as well as their hopes and dreams. Alabado’s book reads like fiction, but was, in effect, I think, a journal of the time she spent with them.

Ceres Alabado’s book, “I See Red in a Circle” included this picture of Philippine Science High School activists demonstrating at Malacañang Palace for more government support (1970).

Alabado writes that these young people were not typical high school kids who were just alternating between classes and the usual teenage pursuits of rock music and girls. They were fired up with patriotic ardor, like the members of the Katipunan,1 the underground organization at the turn of the century that nurtured the Philippine Revolution. To her, these students were the new Katipuneros seeking a new revolution.

IN THOSE TIMES, there was little a parent could do to prevent a determined teenager from joining demonstrations or signing up for one of the radical organizations that sprouted like mushrooms after the First Quarter Storm. After all, it was something romantic to be a student activist. Still, there was more keeping the student movement alive than just the exhilaration of being part of those demonstrations. In time, the marches would have lost their novelty, and the excitement of joining them would have faded. However, the youth now saw themselves as the lead echelon of a growing movement that had the power to radically change Philippine society. Youth who showed little interest in their textbooks were fired up by the writings of contemporary Filipino nationalists. They eagerly read through the anticolonial essays of Renato Constantino. Radicalized, they turned to the speeches and writings of Jose Maria Sison, compiled in Struggle for National Democracy.

Sison’s book, affectionately called “SND” by activists, was a thin volume of 10 essays that described Philippine society as an economic and social basket case. He traced the roots of this condition to Spanish and American colonial acts and impositions that lingered, maintained by native elite that benefited from the status quo. He recalled the efforts of Filipino nationalists like Jose Rizal and the leaders of peasant and labor movements to bring about national and social liberation. Sison urged the Filipino youth to continue their work. He called on them to launch a Second Propaganda Movement (after the intellectuals who fought against Spanish rule at the end of the 19th century) or, referring to Mao Tse-tung’s2 contemporaneous efforts, to work toward a “new cultural revolution.”

Sison’s ideas were later fleshed out and carried further in a second book called Philippine Society and Revolution, initially published as “The Philippine Crisis” in three student publications: Chapter 1 in the UP Philippine Collegian, Chapter 2 in Ang Malaya of the Philippine College of Commerce, and Chapter 3 in the Guidon of Ateneo de Manila. Sison used the nom de guerre “Amado Guerrero,” which he had adopted as chairman of the new Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), and which was also meant to indicate that the writings should be seen as a collective work. “PSR,” as Sison’s second book was commonly referred to, became the bible of the radical sector of the student movement. Those who aligned themselves with Sison’s analysis called themselves national democrats, NDs, or the NatDems.

Sison’s diagnosis of the Philippine condition as being that of a semicolonial and semifeudal state plagued by the three evils of imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism rang true to the youth. The Philippines was a semicolony, no longer ruled directly by American imperialists but kept in a quasicolonial state through laws and trade agreements tying it to U.S. interests, through a government of “brown Americans” and through educational and cultural bonds. The existence of vast landholdings controlled by the local elite pointed to the country’s semifeudal condition. The best way to describe the elite and landlords running the government was to call them “bureaucrat capitalists,” a breed of people who used public office to milk government coffers or gain undue advantage over their business rivals. Sison presented a program for a national democratic revolution for the Philippines paralleling Mao’s successful program for China. It promised a radical cleansing of Philippine society from the three evils.

The self-proclaimed leadership of the National Democratic Movement was the new CPP, with Sison as its chairman. In his eyes, the old Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (dating back to 1930) under the leadership of Jose and Jesus Lava and Pedro Taruc no longer deserved to represent the working masses. The Lavas had thoroughly betrayed the ideals of the Communist Party through a series of grievous ideological, political, and military errors from the post-World War II period until the 1960s. On the one hand, in the late 1940s, they led the anti-Japanese people’s army (the Hukbalahap) to surrender its arms, allowed peasant organizations to be throttled by the local constabulary and landlord agents, and directed mass organizations to participate willingly in landlord politics. On the other hand, in the 1950s, they started a campaign of “adventurist” attacks on provincial capitals and cities, which decimated the people’s army, ending in surrender and renewed support for landlord politics and programs in the Magsaysay period. On December 26, 1968, some intellectuals and labor and peasant leaders met to repudiate the ideological, political, and military errors of the Lavas and re-establish the CPP “on the basis of Marxism-Leninism-Mao Tse-tung Thought.”

Describing Mao’s thought, Sison spoke of liberating the country from its semifeudal, semicolonial state by conducting a protracted people’s war. To be able to engage a people in such a war, a revolutionary party had to live with and be one with the suffering masses who were mainly peasants and workers. The NatDem organizations therefore exhorted their members “to integrate with the masses.” Students in Metro Manila took this to mean working in squatter colonies or venturing into nearby rural areas to learn about the life of the urban and rural poor. A preliminary step was to carry out “social investigation” or “SI” in student parlance. This involved a survey of each area to determine the social class distribution as a prelude to intelligent organizing and political work.

The student activists’ dream, at least for those aligned with the NatDems, was to forsake their lives in the city and to settle in remote rural areas—mamundok, to go to the mountains, a figure of speech that was literally correct because of the mountainous terrain of the Sierra Madre, Bicol, and the northern provinces where they were headed. They were to organize the peasants for self-sufficiency as well as to form their own army. The students spoke of going to Isabela. This remote province far to the northeast was, for city-bred activists, the ultimate destination. The New People’s Army (NPA), the armed force linked to the NatDems, had Isabela for its base of operations. The daunting challenge of leaving family and friends behind to embrace a life of hardship and constant danger working among the peasant masses took on the nature of a Grail Quest, because the writings of Mao and Sison imbued it with a heroic character.

FOR JAN, AS FOR most others in the student movement of the early 1970s, the reading of PSR and the discovery of Mao’s revolutionary theory brought about a kind of enlightenment. Here were the correct ideas and a surefire political formula for success in a revolutionary endeavor. All around me, I could see young people experiencing “illumination” upon reading SND, PSR, and Mao and being fired up with revolutionary zeal. If there was any way for Filipinos to break out of centuries of oppression and betrayal, the national democratic program was it.

I imagine that Jan and most of his classmates at the PSHS had previously aspired to become scientists or engineers. Jan’s ambition now was to become the person described by Mao as a “cadre,” a person totally dedicated to serving the masses in a revolutionary role. He could be compared to a missionary going off to some remote place to live with the natives and win converts to the faith.

Jan was happy visiting and spending time with the squatter families who lived on the future site of PSHS in North Triangle, the area bounded by EDSA (then still Highway 54), Quezon Avenue, and North Avenue. These families eked out a living quarrying blocks from soft volcanic deposits called adobe, which was ubiquitous in the area. They lived in jerry-built shacks with cast-off corrugated sheets for roofing.

Jan wanted to learn about living with the poor in the countryside by spending time with these people. He took me to the place once, and yes, it looked like a provincial area, a place overrun with cogon grass, with the dwellings still sparse, small vegetable plots near the shacks, and ponds where rainwater filled the quarries. He introduced me to a cute, healthy-looking toddler who was one of the attractions of the place for him. This patch of North Triangle (where a huge mall was later to sprout) was Jan’s “little Isabela” in the city. He described the people as really no different from poor families in the countryside. They subsisted on what the land could yield: adobe blocks sold for construction, camote (sweet potato), and fish that appeared in the adobe pits during the rainy season. Their marginal lives were further complicated by oppression by the authorities. Police would pay threatening visits to extract tong for “permission” to quarry. They learned to hide when they spotted policemen coming.

Police fire tear gas to disperse protesters in front of the UP administration building (1971). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

Jan told me about the characters living in this squatter colony. One could romanticize the poor, but Jan understood early on that criminals lived there too—the lumpen proletariat, the dregs of society of Marx’s writings. One of his friends was a tattooed Sigue-Sigue gang member who had spent time in the national penitentiary in Muntinlupa. The Sigue-Sigue and OXO gangs, the two major criminal groups of the time, drew their members from convicts and ex-convicts. This ex-convict would regale Jan with stories of his time inside prison. Once he told Jan, after Jan had napped on the floor of a squatter’s house, that he would have been raped by other convicts if he slept that way in prison. He was quite touched that Jan and his companions were engaged in a movement to uplift the poor, even people like him who had gone over the edge. He said he felt it was too late for someone like him, but he vowed to avoid victimizing other poor people.

How Jan carried on with his personal life was remarkable, but probably no different from hundreds of other young persons who were convinced they were enrolled in the right cause. You could see his self-imposed discipline and the spartan lifestyle of a revolutionary he adopted, as described in Mao’s little red book. I thought he was like a young man studying to become a priest. After returning from a heavy day of meetings or organizing work, he would read Mao or Lenin late into the night (one seldom saw teenagers doing this kind of serious reading) and fall asleep with the book he was reading. The volume would be one of a collection of revolutionary works painstakingly reproduced by the CPP education department. They were mimeographed, pressed between folder halves, stapled at the sides, and bound with masking tape. These books found their way into all the proliferating NatDem organizations.

Though I read Mao, Jan was far ahead of me in understanding his ideas. While I was reading as an academic, he undertook a “living reading” of Mao. He always tried to confirm the correctness of his ideas from experience and to apply the principles he learned to his activist work. When tackling an essay such as “On Contradiction,” more often than not he would be the speaker and I the listener. “On Contradiction” was Mao’s philosophical essay that counseled activists “to observe and analyze the movement of opposites or ‘contradictions’ in such things as the development of a society and, on the basis of such analysis, to see the correct method for resolving these contradictions.”

In early 1970, Jan joined the UP-based Kabataang Makabayan while keeping his ties with MKK, which had become a sort of junior version of KM. This was a step up in his radicalization. KM was considered the leading organization in the radical student movement. Students who considered themselves NatDems, or were attracted to Sison’s ideas of liberating the country by conducting a people’s war, were natural recruits. KM counted among its ranks not only students but also working-class and poor urban youth. Student activists came to know and admire its earlier work with the labor movement. It was seen as the stepping stone to the CPP and the guerrillas in the countryside.

DURING THE LAST WEEK of January 1971, an oil price increase of three centavos per liter triggered demonstrations by students and transport workers. One such demonstration was held in UP Diliman. Hundreds of students formed a human barricade blocking University Avenue, the main UP road leading to the administration building, to prevent vehicles from entering the campus. The success of the blockade inspired transport workers throughout Metro Manila to continue to strike and led to a second blockade on February 1. More students joined the human barricade that once again closed University Avenue. During the demonstration, a UP professor, Inocente Campos, a Marcos loyalist known for his strong antipathy toward student activists, insisted on driving through to the campus. Stopped by the barricade, he remonstrated with the activists. Then, frustrated, he fetched a gun from his car and fired at the students, hitting Pastor (Sonny) Mesina Jr. A college freshman and a member of the NatDem-influenced Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK) or Democratic Youth Movement, Sonny was a 1970 graduate of PSHS whom Jan knew well. He was rushed to the hospital but died three days later. The UP Security Force arrested Campos, and police later forced their way through the barricade and arrested students.

UP students use benches, desks, and chairs to barricade buildings in the UP campus (1971). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

“What started as protests against an [oil] price hike soon grew into a student revolt against [the] violation of academic freedom and police brutality,” recalled Dr. Jeepy Perez, an activist during the 1970s. Stronger and larger human barricades were formed, isolating the campus. Students, faculty, staff, and residents remained within the university premises despite persistent harassment by the military and police. The activists on campus declared the establishment of the “Diliman Commune” inspired by thoughts of the Paris Commune of 1871.

Jan, though at that time still technically a high school senior at PSHS, stayed on the Diliman campus for most of the siege. He joined the human barricades, teamed up with the other radicals who ran it like an activist camp, and remained to defend the area from the police. He would return home just to eat and get a change of clothes. He was part of the Diliman Commune until February 9, when the police and military came in force to remove the barricades and disperse the Communards.

AT ABOUT THIS TIME Jan asked if he could live with us. He felt Bernie and I would understand his predicament because of our strong sympathies for the activist movement, shown by our faithful attendance at rallies. We knew that Jan had nowhere else to stay. His relationship with Dad had long been strained, and going home to 1783-H Concepción Aguila was not an option. Since we had a spare room, we readily agreed to take him in.

Having a room to himself was a novel experience for Jan, as none of the unmarried Quimpo children had ever had this luxury in all the places where we had lived. However, Jan’s room was hardly ideal. Our apartment was the innermost unit, and the sunlight did not penetrate to the back of the apartment where his room was. During the rainy season, it was always damp, and it was soon infested with bedbugs, but he didn’t seem to mind the discomfort.

A car burns on the entrance road to UP as protests continue after the killing of Pastor Mesina at a barricade (1971). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

Jan often visited the KM regional headquarters, which used to be in one of the three-story units in this building on Kamias Street, a short jeepney ride from Norman and Bernie’s apartment in Cubao.

By the time Jan was a high school senior, the PSHS was in complete chaos. A studentry already radicalized by the shooting of Mesina at the UP barricades was further enraged by the death of Francis Sontillano, a senior killed in the violence at a protest rally in December 1970. With daily protests and walkouts from class, it became futile to hold any classes. It was unclear what would happen to the students, especially those supposed to graduate in March 1971. Then, in an unprecedented decision, PSHS decided to allow the “graduation en masse” of students who had begun their freshman year in 1966 and 1967. Jan got the benefit of this mass graduation.

He took the entrance exam at UP, listing B.S. Geology as his course of choice, and passed. He stuck around UP for a semester, but with the growing political turmoil, I could see that his heart was no longer in his studies. One could say that he was in UP only to meet other activists, recruit more converts to the cause, and act in concert with his comrades to maintain UP as a thorn in the side of the regime.

Hardly was his freshman year at UP over when he revealed to me that he had dropped out of school and gone “full-time.” I believe he told me this only when he had already become a full-time activist for some time. From then on, he would usually say, as he was leaving our apartment, that he was going to “HQ,” meaning the KM national headquarters on Quezon Avenue or the KM regional headquarters in a three-story apartment unit near the intersection of Kamias and Anonas Streets. At times he would be gone for days, but I never questioned him on his whereabouts.

If I didn’t see him at home much, I continued to see him at rallies. Once he led a contingent of poor urban youth. He was so light-skinned compared to the sunburned and scruffy youths he led, that he was obviously a student from one of the “better” schools. He wore the same large plastic glasses as in his high school days, giving him an owlish, intellectual look.

But this Jan was no longer the innocent schoolboy excited about entering high school, whose bedding and clothes I had carried with Dad and Mom to his dorm. Once, just back from a demonstration, he pulled out from his pocket the very first “pillbox” bomb I had ever seen, a tinfoil packet with gunpowder and pieces of rock, nails, and shards of glass that fit snugly in his hand. Was bringing an explosive to a rally just a sign of youthful bravado, or was Jan really steeling himself for an anticipated confrontation with the state, in particular with its instruments of coercion, the policeman and the soldier? I didn’t realize that I was seeing then the transformation of the Manila youth of the 1970s, embodied in my brother.

NOTE

1 Katipunan is a Tagalog word for gathering or society. It was shorthand for the organization, whose full name was Kataastaasang, Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Supreme and Venerable Society of the Children of the Nation).

2 Mao Tse-tung was later respelled Mao Zedong.