Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWatching the Storm

5

NATHAN GILBERT QUIMPO

HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION, San Beda College, March 1970. The master of ceremonies called out my name and announced, “Class valedictorian.” Amid warm applause, Fr. Isidoro Otazu, the rector, handed me a small box with a gold medal together with my diploma, and congratulated me. Mom rose from her grandstand seat next to Dad among the special guests. Beaming with happiness and pride, she pinned the gold medal on my brand-new barong tagalog. The medal was one of several I received that evening, and the most important one.

The valedictorian award meant so much to Mom and Dad. They worked very hard to send all their children to schools with high standards, to prepare us for whatever profession we might choose. The medal meant a lot to me too. I had studied hard through all four years of high school. Driven at least in part by personal ambition, I had always aimed for excellence. I felt that at that stage in my life, I was faring very well.

After all of us 180 graduating students had received our diplomas, the master of ceremonies called on me to deliver the valedictory. Walking to the podium, I felt nervous. With the recent wave of nationalist sentiment sweeping the country, there was a clamor for graduation speeches to be delivered in Filipino (called Pilipino until the adoption of the 1987 Philippine Constitution), the national language based on Tagalog, not in English as in the past. I fully supported the idea. Not being a native Tagalog speaker, however, I did not have a good command of Filipino. I wrote my speech in English first, then translated it into Filipino. Somewhat concerned about my language skills, I asked my Filipino teacher at the last minute to edit my speech. To my embarrassment, he replaced huge chunks of my translation.

However, the language problem was only secondary. I felt taut mainly because I was about to comment on the tumultuous events that had shaken Manila and the whole country over the past few months. In San Beda, we had had a ringside view of the tumult in front of the school on Mendiola Street, where the worst rioting had occurred. I wasn’t sure how the audience, including my fellow graduates, would react to my valedictory.

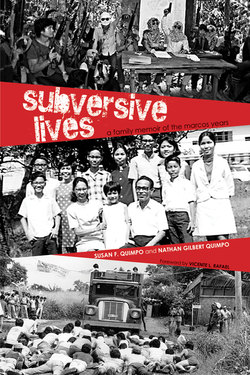

Demonstrators flee police and tear gas in the University Belt during the First Quarter Storm (1970). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

A FEW MONTHS BEFORE, the First Quarter Storm of 1970—“FQS”—had rocked the country. It was a major socio-political disturbance that no one had forecasted.

Throughout high school, I had been active in extracurricular activities (except sports, which I disliked): the student council, the student newspaper, the debating club, cultural activities, various school competitions, etc. But nothing in my student life prepared me for the FQS. The only activities I had engaged in that reflected some degree of social awareness were fund raisers, such as soliciting newspapers and old clothes for the poor or for victims of natural disasters, and teaching catechism on weekends to schoolchildren in a depressed community nearby. I did keep abreast of national political developments and sometimes got into lively discussions in the debating club, without committing myself to any political position, but that was all.

San Beda College, a private boys’ school run by Benedictine monks, stood in the heart of Manila several hundred meters from the gates of Malacañang Palace. Like many other private schools run by Roman Catholic religious orders in the Philippines, San Beda provided an education from grade school to college. It was one of the top exclusive schools that catered mainly to scions of the upper and middle classes, boasting a higher standard of education and charging higher tuition than other schools.

Many protest marches passed in front of the school on the way to Malacañang, but I would only watch them without joining. Like many of my schoolmates, I was a bit scared that violence would suddenly break out. The only violent rally that I could recall had occurred in October 1966, when police forcibly dispersed anti-Vietnam War protesters during the visit of U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. However, I had seen many newspaper photos and much TV and film footage of student demonstrators clashing with the police in the U.S. and other parts of the world. Students of exclusive schools, even those already in college, rarely went to protest rallies. When they did, they joined Catholic-inspired rallies sponsored by such organizations as the Federation of Free Farmers, the Federation of Free Workers, Khi Rho, and the Christian Social Movement, all organizations strongly influenced by Vatican II. For many Sanbedistas (as students of San Beda were called), these rallies were merely an occasion to ogle and socialize with colegialas.

Mom pins a medal for academic excellence on Nathan’s shirt at a high school award ceremony in San Beda College (1969).

In mid-January 1970, the student body of San Beda High School was invited to join a big rally scheduled on January 26 in front of Congress. The invitation was coursed through our student council, of which I was the secretary of external affairs. The organizer, the National Union of Students of the Philippines (NUSP), timed the rally for the opening of Congress, during which newly reelected President Ferdinand Marcos would deliver the annual state of the nation address. The NUSP, a union of student councils from all over the country, was prestigious and considered responsible. It was led by Edgar (Edjop) Jopson, student council president at Ateneo de Manila University, considered the leading private boys’ school in the land. Prior to the rally, the NUSP issued a manifesto calling on political parties not to interfere in the Constitutional Convention (“Con-Con”)1 slated to be convened in 1971. A growing number of the populace, especially among the youth, distrusted politicians and the two main political parties, the Nacionalistas and the Liberals, as representing the landed elite and vested interests and further enriching themselves in office. These politicos blocked meaningful social reform, preserving the skewed distribution of wealth in defiance of the growing antagonism between the have-nots and the haves, oblivious to the social volcano about to explode. Many reform-minded people looked at the Con-Con as the last chance to institute fundamental change and prevent a bloody revolution; they wanted politicos to keep their dirty hands off the Con-Con.

The student council in my last year in high school was far more active and energetic than in other years, and effective at stimulating student involvement in school and civic activities. With the civic-spiritedness promoted by the council, it was easy to commit Sanbedistas to participate in the NUSP rally.

It was my first big rally, but I had no cause for concern. A majority of students were participating, with parental approval, and some of the faculty were also joining. Students from many other religious-run schools would be there. Our school administration endorsed participation, with the implicit backing of the Catholic Church hierarchy. The day before the rally, the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines issued a “prayer” for a nonpartisan Con-Con. What could possibly go wrong?

In our school uniforms, we marched, in neat rows under the hot afternoon sun, from school all the way to Congress, as we did during San Beda’s annual procession for the Holy Infant of Prague, though without the candles. Some of my schoolmates, kids of 12 or 13, were getting a taste of the parliament of the streets for the first time. We proudly carried our school’s red-and-white banner, as well as posters and placards calling for a nonpartisan Con-Con.

Thousands were at the rally site—it was the biggest student rally I had seen. Colorful banners and streamers, mostly red and white, fluttered in front of the legislative building. Some carried slogans, others the names of schools or organizations. Placards were hoisted everywhere. Student leaders took turns addressing the crowd. They lambasted President Marcos and Congress for graft and corruption, for campaign irregularities and violence during the elections two months before, and for failing to enact land reform and other basic reforms. Some speakers used profane language and cracked off-color jokes that made the crowd roar, but sometimes made me flinch. In one section of the crowd, a boisterous group chanting militant slogans repeatedly interrupted the speakers. “Ibagsak ang imperyalismong Kano! (Down with U.S. imperialism!)” “Marcos, papet! (Marcos, puppet!).” The slogans seemed to me off-tangent, completely unrelated to the theme of the rally. I couldn’t understand what those rowdy demonstrators were doing as part of our rally. The names on their streamers read Kabataang Makabayan (KM), Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK), and Lyceum of the Philippines. From time to time, rally organizers pleaded with the unruly rallyists to pipe down.

In general, however, the rally was peaceful and orderly, and I felt that it had been a worthwhile experience for my schoolmates and myself. Good for developing social and political awareness, I thought. Never mind if most of my fellow Sanbedistas, who were used to basketball and parties after school, had left after less than an hour at the rally. I stayed until 5:30 p.m. The rally was not yet over, but I must have been one of the last from San Beda to leave.

HALF AN HOUR AFTER I got home, my sisters Caren and Lillian arrived, very agitated. They had been at the rally too, together with other colegialas from the College of the Holy Spirit.

“Hay, naku!” Caren exclaimed. “A riot broke out at the rally! We had to run to get out safely.”

“What?” I asked in disbelief. The violence must have erupted soon after I left.

I turned on the radio, tuning in to “Radyo Patrol.” Dad, Mom, Caren, Lillian, Ryan, Jun, and Susan huddled close by. On-the-spot reporter Orly Mercado was excitedly giving a blow-by-blow account of what was happening in front of Congress. According to Orly, as Marcos and his wife, Imelda, stepped out of the legislative building to board their car, student demonstrators chanting “Marcos, papet!” pushed forward a cardboard coffin symbolizing the death of democracy, and threw toward them a burning papier-mâché crocodile, symbolizing greed.

The demonstrators surged forward, and as the Marcoses fled in the presidential car, their cordon of police and soldiers of Metrocom (the Philippine Constabulary’s Metropolitan Command) pushed the demonstrators back, swinging rattan truncheons. In response, the demonstrators threw stones, soda bottles, and the sticks from their placard frames. Riot! The police chased and beat demonstrators, who fought back shouting, “Makibaka, huwag matakot! (Fight on, take courage!)” Several times the cops charged; the demonstrators, regrouping, countercharged.

It was an uneven battle—the police and Metrocom with crash helmets and wicker shields, swinging truncheons, while the demonstrators fought with whatever they could lay their hands on. From Congress, the clashes spread to as far as Luneta Park, City Hall, and Intramuros. The battle raged for over two hours. Dozens of demonstrators, innocent bystanders, and policemen were hurt; fortunately, no one was killed. Many demonstrators were arrested.

We all felt anxious about my brother Jan, who we all presumed had also gone to the rally. Jan, one and a half years younger than I, was staying at his school dormitory. The year before, he had joined the Malayang Katipunan ng Kabataan (MKK) at his high school, which for two years had been a breeding ground for young militants.

Student leader Portia Ilagan addresses a rally for a peaceful Constitutional Convention outside Congress (January 26, 1970). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

Later that night, after making a number of calls from the house of neighbors who kindly let us use their phone, we found, much to our relief, that Jan had arrived at the dorm safely. Dropping by the house the following day, he admitted having gone to the rally. He told Dad and Mom that he left when the violence started. He confided to me, however, that he stayed on and joined the crowd throwing stones. With a foreboding that a period of disorder and turbulence had just begun, I urged him to take care.

Scenes of the rioting and the beating of demonstrators were splashed all over the newspapers and aired over and over on TV; radio commentators talked about virtually nothing else. Congress ordered an immediate investigation. Public sympathy was overwhelmingly on the side of the demonstrators. The violence was blamed on provocateurs and on the Metrocom and the police. Prominent personalities criticized their use of excessive force. Student leaders decried police brutality.

Several marches to protest the violent suppression of the January 26 rally were quickly organized for January 30. The main converging points were Congress and Malacañang. Student and youth organizations all over Metro Manila girded for action. The whole city was tense, fearful of another violent confrontation between the police and the demonstrators.

Should I join? Deep inside me, I was angry about the treatment of demonstrators. And I had lost my fear of rallies. I thought I could always keep away from the frontlines and leave at the first sign of a disturbance, but Dad and Mom stood in the way. “No, you may not go,” they said. “You’re too young for such things.” There could be no argument. At home, as long as we were minors, under 21, Dad and Mom were fully responsible for us, our food, health, and education, but we had to follow their rules. I was a good kid who obeyed their rules and did well in school. So I stayed home. I did not have to go to San Beda as classes had been called off.

In the early afternoon of January 30, the scheduled day for the new protest, a large group of demonstrators passed our apartment building on Concepción Aguila Street. I rushed out and watched them pass. I felt the urge to join but restrained myself. I wondered about Jan who was probably out there somewhere. Dad and Mom hadn’t had the opportunity to visit him at his dorm to expressly forbid him from participating. Through the rest of the day, I stayed glued to the radio.

The rallies at Congress and Malacañang stretched on for several hours with no untoward incidents. A delegation of moderate leaders headed by NUSP president Edjop Jopson entered Malacañang in mid-afternoon for a dialogue with President Marcos, while the NUSP demonstrators and other moderate groups continued to rally outside. As dusk fell, the rallyists at Congress, from KM, SDK, and other militant youth organizations proceeded to Malacañang and joined the moderate demonstrators. The crowd grew restless. When the Malacañang lamps were turned on, a number of demonstrators stoned and smashed them despite appeals from the rally marshals. Suddenly, fire trucks arrived at the scene. Firemen blasted the demonstrators with water from the trucks but were unable to disperse them. Demonstrators swarmed onto a fire truck, took it over, and rammed through the Mendiola gate of Malacañang. Once inside, they stormed some small buildings near the gate, lobbing not just stones and bottles but also crude explosive devices that I had not heard of before—Molotov cocktails and pillboxes. Apparently, the demonstrators had come better prepared this time.

Gunshots! The presidential guard emerged and started firing in the air. Then teargas. The demonstrators retreated. Police reinforcements and units from the Metrocom, the army, navy, marines, and Special Forces advanced from many directions. A seesaw battle ensued, with each side alternately charging and retreating. The rallyists gradually lost ground and were eventually pushed back, out of Malacañang, down Mendiola, some toward Concepción Aguila Street but many in the other direction, across Mendiola Bridge2 to Recto Avenue and Legarda Street, the center of the University Belt with its dense concentration of colleges and universities. Fleeing from truncheon-wielding police, scores of demonstrators clambered over walls and gates and into the yards of houses and school compounds. Over two hundred demonstrators sought refuge in San Beda College.

But the demonstrators still had some fight left. Hundreds regrouped and marched to retake Mendiola Bridge. As they approached, the soldiers on the bridge fired their Thompson submachine guns into the ground. The demonstrators scattered, several hit by ricocheting bullets or fragments. The soldiers charged as the demonstrators retreated back to the University Belt. Doors opened; some of the rallyists scrambled into student dormitories and boarding houses. The more daring remained on the streets and in the alleys to carry on the fight. As the night wore on, demonstrators ripped out the iron railings on the traffic islands along Recto and set up barricades along the avenue, piling up old car tires and trash and setting them on fire. The police tear-gassed the whole area and barged into student dormitories, arresting and beating up demonstrators who had taken refuge there.

The Battle of Mendiola Bridge lasted for seven hours. It was the most violent demonstration in the country’s history, until then. The next day’s newspapers reported that four students had been killed—the number was later revised to six—and scores of others had been wounded. Some of those killed or wounded were innocent bystanders. Over three hundred were detained. Marcos, appearing on TV, denounced the militant demonstrators as “insurrectionary elements,” claiming that they had conducted “a premeditated attack on the government, an act of rebellion and subversion” that was communist-inspired.

THE WHOLE COUNTRY was in a state of shock. Never had Filipinos seen or heard anything like what they had witnessed on January 26 and 30. Student leaders intensified their charges of police brutality, but the more militant elements denounced the “fascism” of the state. The word confused and bothered me. In the past, I had associated the term only with Mussolini and Hitler. I was further disturbed when I learned that Marcos, in his January 30 meeting with moderate student leaders, had refused their demand for him to sign a pledge not to run for a third term in 1973. Elected in 1965 and reelected in 1969 in what was reputed to have been the costliest, dirtiest, and bloodiest election in Philippine history, he was constitutionally prohibited from running again. However, even then, near the start of his second term, suspicions were rife that he was plotting to remain in power beyond 1973.

In the weeks that followed, youth and student rallies, “people’s marches,” and other protest actions followed one after another in quick succession. On days of major demonstrations, the Department of Education called off classes and shopkeepers on the main routes of the rallies closed shop early, boarding up their glass doors and windows. Violent clashes between cops and activists became a common occurrence. Most of the battles took place in the evening or at night in the vicinity of Mendiola and the University Belt. The area around the U.S. Embassy on Roxas Boulevard also became a frequent scene of violence. On February 18, demonstrators stormed the embassy, smashed windows and set a bonfire in the lobby, burning chairs and tables. In subsequent rallies, they pelted it with stones and pillboxes. Meanwhile, the military raided the campus of the Philippine College of Commerce in the University Belt, which they suspected of being a center of leftist activity. As the tumult in the streets continued, Marcos publicly warned that he was seriously considering declaring martial law or suspending the writ of habeas corpus. I wasn’t much bothered by Marcos’s threat, because I had only a vague idea of what martial law meant, and I didn’t understand what habeas corpus was.

After my first rally, I took no part in other street actions through the rest of the period that activists dubbed the First Quarter Storm of 1970. Apart from being under the watchful eyes of Dad and Mom, I became preoccupied with studying for my final exams and preparing for graduation. However, the rallies constantly reminded me of the events of January 26 and 30.

Once, when I stayed overnight with a friend, I had a graphic reminder of the need for caution. Gerundio (Bogs) Bonifacio was a colleague in the debating club; his family’s apartment overlooked Mendiola Bridge. A rally that afternoon had turned by evening into another melee. I peered out the window, curious to see an actual skirmish between police and activists. The streets were deserted except for a bunch of cops with gas masks, truncheons, and shields on one side of the bridge. Lighted by streetlamps but shrouded in teargas, Mendiola Bridge took on a strange, surreal quality. Suddenly, a young militant darted out of a side street near Legarda and threw what must have been a pillbox. Blam! The cops charged after him. I leaned out to see if the cops had caught him. Bogs yanked me away from the window. “Don’t be a fool,” he said, closing the shutters. “You can get hit by stray bullets.”

In between my studies, I helped organize school forums and discussions on the burning political issues driving the rallies. Some of us had heard about teach-ins and “DGs” (discussion groups) conducted by activists, usually outdoors, on campuses or in slums and poor neighborhoods all over Metro Manila. They were supposed to be an alternative to the formal classroom lectures provided by the Philippine “neocolonial” educational system. In the teach-ins, one learned about all the bad and the good isms: imperialism, neocolonialism, feudalism, bureaucrat capitalism, fascism, socialism, and communism. Along with mass protest actions, the teach-ins were part of the process of politicization to “raise one’s political consciousness.” For the biggest forum we organized, the student council invited the NUSP, other youth and student groups, and farmers’ and workers’ organizations to speak in front of all the high school students at our basketball court. To enable students to attend, we secured the suspension of classes for a few hours from the school administration. Though we had not been out on the streets again, we felt very proud of our first large teach-in.

I SYMPATHIZED A GREAT deal with the activists. The country was going to the dogs; life seemed to be growing more and more difficult for most Filipinos. Yet no one seemed to be doing anything about it.

My family felt the pinch. Still, we were better off than many other families. Every day, on my way to school, I walked by a small, congested community of shanty dwellers squatting on land they did not own. Aling Conching, who came thrice a week to do our laundry, lived there with her two sons in a one-room, 2-by-3-meter barong-barong fashioned out of discarded pieces of wood and galvanized iron, with no running water, no toilet, and no bath. A narrow strip of barong-barong also occupied the other side of an estero (creek) right next to San Beda. From our classroom on the second floor of St. Anselm’s Hall, we could sometimes smell the stink from the creek, heavily polluted by the garbage from a public market a few hundred meters upstream. I couldn’t imagine myself living in such conditions and inhaling the stink the whole day.3

To me, the urban slums were blatant evidence of an unjust and inhuman social order. From school and from the newspapers, I learned the statistics of social injustice. The richest 20 percent of the population controlled 56 percent of the country’s total income, 16 times the share of the poorest 20 percent. The country’s poverty incidence stood at 67 percent. Millions of farmers didn’t own the land they tilled, working for landlords with vast tracts of land, who took as their share up to two-thirds of their crops. A typical factory worker was paid eight pesos a day, a pittance compared to the huge profits of the factory owner, and grossly inadequate to feed an average family of six.

Since I had not gone out to “integrate” with farmers and workers, the figures remained abstract to me. But the sight of the slums pierced me to my heart. I would compare those barong-barong to the plush mansions of Makati’s beautiful people, with their spacious, air-conditioned rooms, manicured lawns, swimming pools, and security guards. Some of my classmates would be chauffeured from these mansions to school every day. Uniformed yaya (nannies) had accompanied them when we were in elementary school. Amid the city’s poverty, the rich flaunted their wealth; their stylish clothes, sleek limousines, armed bodyguards, lavish parties, and junkets were written about in the society pages and gossip columns of newspapers.

In the weeks after the rallies of January 26 and 30, I found out more about the various youth and student activist groups and the differences in their ways of thinking, their goals and means. The groups competed fiercely for recruits and hurled insults and pinned labels on one another. There were clerico-fascists, pacifists, rightists, centrists, leftists, ultra-leftists, Maoists, and revisionists. The main divide appeared to be between reformists and revolutionaries, or moderates and radicals. Groups such as the NUSP were moderate; they worked for social reform through peaceful, parliamentary means. The moderates were mainly based in religious-run schools, but they also had followings in some state-run and private non-sectarian schools. The radical organizations included KM and SDK, which advocated a complete overhaul of the unjust social order through armed revolution. They drew many members from state-run universities and colleges such as UP and private, non-sectarian schools, including the substandard diploma mills that produced graduates en masse at great profit for their owners. The radicals also attracted young workers and poor out-of-school youth. The government regarded these groups as mere fronts for illegal, subversive organizations such as the Communist Party of the Philippines.

During the First Quarter Storm, none of us in San Beda High School actually joined an activist group. Those sympathetic to the activists were drawn toward the moderates, but not I. Perhaps my family situation affected me. Perhaps Jan had influenced me. Within a few weeks, I lost any hope of meaningful social change through purely parliamentary means. Still, I was not a revolutionary; I was still hopeful of averting a violent conflict that could cost countless lives. I believed that extralegal actions short of revolution were necessary to break out of social apathy and generate meaningful change. Some degree of violence in the struggle against social injustice was regrettable but understandable, and perhaps even justified.

DELIVERING THE VALEDICTORY before the Class of 1970 of San Beda High School, I veered away from the nonviolent credo espoused by the Church and by the moderate activist groups. I said:

Belonging to the country’s upper and middle classes, we—or most of us, at least—have lived sheltered, comfortable lives. We live in fine houses or apartments and eat three full meals a day. We study in an exclusive school and receive the best of liberal education. We go the movies every once in a while, have parties and festivals, and cheer ourselves hoarse at NCAA games.

Over the past few months, however, we have been witness to a storm, a mighty social storm, that has somewhat intruded into our sheltered lives. On our TV screens, we’ve watched how protest rallies have turned into riots, street battles, and melees. We’ve seen how soldiers and policemen have beaten up demonstrators, and fired their guns and killed or maimed scores of people—protesters and onlookers alike. We’ve seen how demonstrators have hurled stones and rocks, Molotov cocktails and pillboxes against the police and military. Shocked and aghast, we’ve joined the civic-minded sectors of society in condemning the violence of both sides and calling for sobriety. But this is as far as we’ve gone.

Soul-searching, I’ve asked myself why protesters risk their lives in the face of police brutality and why they have resorted to violence themselves. I believe that they are trying to open our eyes to the world outside our sheltered existence. Their anger and fury have been directed against an unjust social order in which an elite few controls the country’s wealth and power, while the overwhelming majority of our countrymen and women wallow in poverty and misery, and in which the gap between the rich and the poor, instead of narrowing, has become a gaping chasm. In resorting to drastic means, the protesters seek to shatter the apathy and inertia in Philippine society and impel structural change. The stones, Molotovs, and pillboxes have to be seen in their proper perspective. We cannot expect the struggle against the institutionalized violence of social injustice to be entirely peaceful.

We cannot just stand aside and watch the storm. As Filipinos concerned for our country and the well-being of all our people, we have to take part in dismantling the structures of oppression in order to bring about a truly just social order and to prevent a cataclysm. Let us be part of the winds of change.

My speech was received with prolonged and hearty applause. Beaming, I returned to my seat. I wondered later if what I said would have any real impact on my fellow graduates. I didn’t realize what a profound impact those events would have on my own life.

NOTES

1 The convention, members of which were soon to be elected, was being convoked to revise the 1935 Philippine Constitution, approved when the Philippines was still a U.S. colony.

2 Recently renamed Don Chino Roces Bridge after a leader of the protests against Marcos.

3 Even worse was what I had heard of Smokey Mountain, the huge slum in Tondo built on a mountain of garbage, where tens of thousands made their living by scavenging in the dump. The reports of rotting garbage emitting acrid or even poisonous fumes and sometimes catching fire made me shudder and think of it as the most terrible place in the world to live.