Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Radical Activist at an Elite University

8

NATHAN GILBERT QUIMPO

AFTER GRADUATING FROM San Beda High School, I set twin goals for myself: to continue my education and to pursue social justice. I won a scholarship from Insular Life that allowed me to choose my college. I chose Ateneo de Manila, reputed to be a university of the elite, over UP, the activist-infested state university. Though my elder brother, Norman, had graduated from Ateneo and was now teaching there, my choice had more to do with balancing studies and extracurricular activities, which I felt would be difficult among the radical militants running loose in UP. I was confident that I would avoid being seduced by the elitist and burgis (bourgeois) ways of Ateneo. In the event, pursuing both goals together was complicated.

Ateneo had two dormitories on campus, Cervini and Eliazo Halls. With an additional “dormitory scholarship” from Ateneo, I stayed at Cervini. Though not air conditioned like Eliazo, it had comfortable rooms and adequate facilities, not luxurious but a vast improvement over the cramped conditions at home. Residents of the dorms even had exclusive use of an outdoor swimming pool. All freshmen students and most “dormitory scholars” stayed at Cervini, whereas upperclassmen who were sons of big businessmen, sugar hacienderos, logging concessionaires and cattle ranchers stayed at Eliazo.

I shared a room with Bogs Bonifacio, my schoolmate from San Beda, and two other students, Kiko Villanueva and Pedro de Guzman, who both hailed from the rice-growing province of Nueva Ecija.

It didn’t take me long to adjust to life in the dorm and the academic routine. Ateneo was conducive to study. The sprawling campus was perched on top of a hill overlooking Marikina Valley, quiet and peaceful, far from the hustle and bustle, the traffic snarls, and polluted air of Manila. Whether on a bench, on the grass, or under a tree, I never had any problem focusing on my studies. At Cervini, resident Jesuits or lay teachers maintained a quiet atmosphere. In the evenings, if I didn’t want to be disturbed by the light conversation of my roommates, I could walk to the air conditioned library, which was open until 10 p.m.

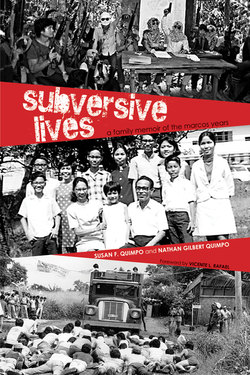

Mom signs the contract for a four-year college scholarship for Nathan, which he won in a citywide competition. Percy Roa, of the Insular Life Assurance Co., which funded the scholarship, looks on.

The calm on campus was reflected, less benignly in my view, in the extracurricular scene. I had high expectations, given the prominent role that Edgar (Edjop) Jopson, the previous student council president, had played earlier in the year in the national student movement. My first few weeks were disappointing. After the protests and tumult in front of San Beda, the university atop Loyola Heights appeared insulated from the outside world.

The student council was not into political activism. The first issue that school year of the student newspaper, the Guidon, had some feature articles by left-wing writers and by the apparently radical Ligang Demokratiko ng Ateneo (LDA) or Democratic League of Ateneo, but overall, the paper was tame compared to UP’s Philippine Collegian. The student clubs looked uninteresting, though I grudgingly signed up for a few. Some moderate activist groups were involved in Operasyon Bantay, a series of protest actions over the burning of two barrios in Bantay, Ilocos Sur, whose residents had voted against a local political warlord in the last election. A few radical activists, mostly members of LDA, were focusing on “mass work” off campus—propaganda, political education, and mobilization among factory workers and the urban poor. Perhaps work on campus was futile; the bulk of the Ateneo studentry may have been too burgis to be politicized.

The closest thing to political activism that seemed to have broad appeal among Ateneans was a “Filipinization” movement promoted by the student council and other student organizations. They demanded that American Jesuits turn over policymaking posts they still held to Filipino Jesuits and lay personnel. Filipinization sounded parochial and out of date to me, harking back to the 1870s when Filipino nationalists were demanding autonomy, not yet full independence, from Spanish rule.

Politically awakened by the First Quarter Storm, I wanted to deepen my politicization. I also wanted to help promote political consciousness and social involvement, particularly among my fellow students, to expose them to the different currents of the movement for social change—moderate, radical, revolutionary, etc. Unlike the few radicals on campus, I still entertained the hope of politicizing an appreciable number of Ateneans, especially among the scholarship students like myself, who were from poor or lower-middle-income families.

The best vehicle for politicization still seemed to be the student council. If it did not seem as activist as I had expected, perhaps I could help change that. I decided to run for one of the three council seats for freshman representative.

UNLIKE THE ELECTIONS for most positions on the council, which were held in the last few weeks of the school year, elections for freshman representatives were held at the start of the school year. Running on a platform of promoting social and political involvement and students’ rights, I had my first taste of Ateneo campus elections. I campaigned hard, with only a vague idea of my chances of winning. Some candidates came from Ateneo High School and had the advantage of being known to most freshmen. What I had going for me was that I had helped start a campaign against “initiation rites” (a euphemism for bullying) which freshmen had been subjected to. With the help of my dorm mates and former schoolmates from San Beda, I barely made it, winning the third and last seat.

On the student council, I soon found out that, like me, many of those elected the previous school year had run on a platform of working for greater social and political awareness among Ateneans. The difference was that their advocacy for political involvement had come under the banner of Filipinization. In discussions with them and other politically involved upperclassmen, I learned that the Filipinization movement had a longer history and broader goals than I had earlier thought.

The opening salvo had been fired in 1968 when five Ateneo student leaders published a manifesto titled “Down from the Hill” in the Guidon, in which they called attention to the “revolutionary” situation in the Philippines and the need to radically restructure the unjust social, political, and economic order. They criticized Ateneo and the Jesuits for serving the oppressive power elite and for providing a Westernized education irrelevant to the country. They called for Filipinization, which to them was simply “making things relevant to the Philippine situation.” They urged not only that university policy be determined entirely by Filipino Jesuits and laymen but also that the university curriculum be drastically reoriented to encourage identification with the masses and greater responsiveness to the country’s needs.

Since the 1968 manifesto, important gains in Filipinization had been made: replacing American with Filipino Jesuits in key positions, such as the rector-president and the dean of arts and sciences; instituting a philosophy course in Filipino; establishing a Philippine Studies Program; and shifting the Guidon from English to Filipino. At the end of the previous school year, newly elected student council president Roger (Brick) Reyes submitted a new manifesto to the Academic Council, the college’s highest policymaking body, recommending changes in the curriculum and administration, such as a required course in Filipino, encouragement for social action projects, the hiring of nationalist professors, and procurement by the library of leftist books. The manifesto had the support not only of the student council but also of the Guidon, virtually all the traditional student organizations, and all the activist groups.

Had I been too hasty in thinking that Ateneo was detached from the nationalist ferment sweeping the country? The Filipinization initiatives attracted me, but within a few weeks of being on the council, I felt frustrated again. The council and other groups launched a Linggo ng Himagsikan (Week of the Revolution), with an exhibition and lectures by noted nationalist writers. Few Ateneans attended. Some activist groups agitated for a boycott of classes on the final day of the Linggo, but the dean of students, Rafael Chee Kee, stepped in to prevent them from disrupting classes. Somewhat progressive in his political outlook, Dean Chee Kee actually sympathized with student activists. He enforced university rules to the extent he had to, though he later proved too softhearted to really crack down.

The Academic Council was to meet on the Filipinization manifesto, and the student council announced a picket to demand that American Jesuits on the Academic Council, the most vocal opponents of Filipinization, recuse themselves. Instead, the administration canceled the meeting. The student council called for a boycott as a result, but few students responded.

The student council turned its attention to arousing student interest in the Constitutional Convention or Con-Con, as the election of delegates was imminent. With the student council of St. Theresa’s College, an exclusive girls’ school, they planned a mock Con-Con, with students of each school electing student delegates. Most of the council members were enthusiastic, but it was a turn-off for me. I no longer believed that the Con-Con could bring about substantial social reform.

Nathan (second right) takes a break with other high school student leaders during a recruitment seminar at the Ateneo de Manila University (1969).

This council project impressed on me the fact that all the key figures on the council were political moderates, and the others, who were largely apolitical, followed their lead. Though I got along well with everyone on the council, I felt powerless to change the situation. I had little influence as a freshman, a newcomer and the only radical member—and one with only a small support base among students. Inhibited from proposing my own ideas for politicization or Filipinization, I became increasingly alienated from the council with its moderate politics and lackluster performance.

In the other student clubs I joined, nothing much happened, as I had feared. The exception was Heights, the literary journal, which was dominated by left-wing writers. Still, not having the confidence to contribute literary pieces, I could only attend to technical matters at the journal. The other traditional school organizations, other than the sports clubs, held few meetings and were largely inactive.

I WAS DRAWN by default to radical student activism. I avidly read leftist leaflets and publications distributed by radical militants. Some of them made favorable, occasionally glowing comments about the outlawed CPP and its guerrilla force, the NPA. A few times I got hold of copies of Ang Bayan (The People), the mimeographed CPP newspaper with a hammer, sickle, and rifle depicted on its logo. This was the first time I had ever seen pro-CPP literature. I had been taught that communism was totalitarian, godless, evil, and subversive, but exposure to unconventional thinking in high school had made me more open-minded and curious about what the radicals and the CPP had to say. Slowly, I absorbed some of what I read. In lively discussions with my dorm mates about politics, I found myself defending radical positions.

Without my parents’ permission, I joined mass actions of radical groups in downtown Manila, where I sometimes bumped into Jan and his friends. I had to cut classes sometimes to do so. But months of virtually nonstop protest rallies, often marred by violence and little resulting political change, made me begin to doubt the efficacy of limited violence. The radicals were probably right that oppression and injustice were so deeply rooted that only a violent revolution could succeed in eradicating them.

I had to join an activist organization. The main radical group at the Ateneo, LDA, struck me at that time as lacking national scope or stature. Kabataang Makabayan (KM), the most militant organization of all, appealed to me, but so did Malayang Pagkakaisa ng Kabataang Pilipino (MPKP), which appeared to attract many intellectuals, including a handful of members at Ateneo. Perhaps partly because I wanted more action and adventure, I opted for KM.

Given the absence of a KM chapter at Ateneo, three dorm mates and I invited a KM leader from UP, Bonifacio (Boni) Ilagan, to explain to us its history and program. Though we did not fully understand all his terms and concepts, we were ready recruits. We set up an Ateneo chapter of KM, with myself as chairman, and started recruiting more members. Only later did I become aware of ideological differences between radical groups, and that I had chosen alliance with the Mao-influenced Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) through KM, over alliance with the old-line pro-Soviet Partidong Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP)1 through MPKP.

MEANWHILE, THE STUDENT council was doing no better than before. The mock Con-Con was a big flop. Few Ateneans attended the teach-ins and less than one-third of the students cast ballots in the election for mock Con-Con delegates. The St. Theresa’s College council officers, who succeeded in eliciting much better participation, were aghast. The mock Con-Con itself failed to produce a draft Philippine constitution as had been intended. In the midst of the fiasco, LDA, which had decided at the last minute to participate, scored some propaganda points. “For me, the mock Constitutional Convention is a comedy,” declared one of the delegates, Perfecto (Boy) Martin, in an interview with the Guidon. “It is a preview of what is going to happen in the real Constitutional Convention.”

The LDA tactics were indeed a preview of what the NatDems were doing nationally, participating in the Con-Con elections mainly to expose the convention as a farce staged by the ruling elite to head off an armed revolution of the masses. NatDems actively supported the candidacy of former UP student council chairman Enrique Voltaire Garcia III, a young and popular leftist. In the actual Con-Con elections in November, Garcia handily won a seat.

AFTER THE MOCK Con-Con debacle, the membership of LDA grew rapidly, even though its organizing efforts had been focused outside campus. The growing opinion within radical ranks was that a substantial number of Ateneans, possibly even a majority, could be radicalized or could at least become sympathetic to the radical cause.

Soon the radical groups on campus, including our newly established KM-Ateneo, were conducting teach-ins and discussion groups right in the middle of the college quad. Sitting in a circle on the grass, we would read aloud passages from a leftist publication or manifesto and position papers on the burning issues of the day and debate the fine points for an hour or two. Among our favorite reading materials were Sison’s Struggle for National Democracy and Mao’s little red book. We all called each other kasama (comrade). Sometimes we would proudly wave red flags and banners with group emblems or slogans. A kasama would strum a guitar during breaks when classes would not be disturbed, and we would sing progressive or revolutionary songs. Not to be outdone, the moderate activist groups—Kilusan ng Kabataan para sa Kalayaan (KKK) or Movement of Youth for Freedom, Kapulungan ng mga Sandigan ng Pilipinas (KASAPI) or Assembly of Pillars of the Philippines, and Lakasdiwa (Strength of Spirit)—soon also held quad discussions and group singing. All factions distributed leaflets and publications, and everyone competed at “operation dikit,” painting radical slogans in red on old newspapers and posting them on bulletin boards and walls.

Perhaps the emergence and growth of our new KM chapter contributed to an LDA reorganization. As I learned then, it had been set up jointly by SDK and the broader KM organization shortly after the First Quarter Storm because two separate chapters seemed too many for our small university. However, LDA was finding it increasingly difficult to carry out the programs and follow directions from two separate, albeit fraternal, national organizations. LDA reorganized to become SDK-Loyola, and four members moved over to join us in KM-Ateneo. We heartily welcomed the four: Rigoberto (Bobi) Tiglao, Ferdinand (Ferdie) Arceo, Boy Martin, and Emerito (Baby Boy) Paulate. Though we now had 30 members, these four were among the minority—about a third—who could be considered active. Our leading members, some of whom were on the dean’s list and were well known on campus, also included writers Manuel (Manolet) Dayrit and Conrado de Quiros.

By my second semester at Ateneo, despite my earlier misgivings, the NatDem radicals had taken center stage in campus politics. Issues of the Guidon before and after the Christmas break carried, in installments, the third chapter of Sison’s “ The Philippine Crisis,” where he arrived at the point of arguing for a “people’s democratic revolution” to be led by the CPP. The installments had been approved for publication under the new editor, who had topped the editorial exams for the Guidon, KM’s Manolet Dayrit.

A FUROR AROSE early in the semester regarding a new textbook in English literature, a required course for all freshmen. Invention consisted of essays compiled by Fr. Joseph Landy, an American Jesuit at the university. Nine Filipino faculty members teaching English issued a manifesto objecting to Invention’s “colonial and reactionary” viewpoint and declaring the book a hindrance to Filipinization.

I fully agreed; I found it to be a typical Western-oriented English textbook, despite the inclusion of a few articles by Filipino authors. I felt that the editor had been insensitive to, or perhaps even unaware of, the rising nationalist and anti-neocolonial consciousness sweeping the country.

For me, as for other NatDem radicals, the issue was not just the Western orientation of the book. The summer before entering Ateneo, I had avidly read some essays of the nationalist historian Renato Constantino and had become convinced of his view that the entire Philippine educational system was neocolonial. The use of English as the medium of instruction, a part of the American colonial legacy, had created a huge gap between an English-speaking elite and the great majority of Filipinos. The Western content and orientation of textbooks added to this alienation of the educated. I could still remember learning to read and write through stories about middle-class American children—John, Jean, and Judy, their dog Spot and Judy’s teddy bear, Tim. We learned about apples and pears, cowboys and Indians, Thanksgiving and Halloween, snowmen and Santa Claus, all of which were alien to the concrete realities of a tropical Third World country.

KM-Ateneo, SDK-Loyola, KKK, and Lakasdiwa issued position papers criticizing Invention as fostering a colonial mentality. With the student council’s endorsement, the freshman council asked for a revision of the book and called on students and teachers to “struggle against the neocolonial system of education.” But when it came to campaigning against Invention, my colleagues in the freshman council balked. I found myself, with Tom, a radical-leaning freshman who had come from a public high school, thrust into the forefront, speaking to class after class and gathering signatures on a petition. The protest culminated in a symbolic burning of a pile of books and an effigy of Uncle Sam in the college quad. We could not afford more than one copy of Invention to burn, but, appropriately the other books were old textbooks distributed free to public schools by the U.S. Information Service.

Eventually, most freshman English teachers replaced Invention with a hurriedly assembled compilation of essays, Perspectives. I expected my English teacher, Fr. James Donelan, to insist on using Invention. An Irish-American Jesuit, Father Donelan had been one of the most affected by the Filipinization movement. He had been president of the university until 1969, when he was pressured to resign in favor of a Filipino Jesuit. Instead of retiring, he went back to teaching. Kind and gentle, Father Donelan had a quiet dignity. He was fair and even indulgent toward everyone, including me, even when he knew that I was radical and one of the leaders of the anti-Invention campaign. He asked the class to vote on what we wanted to use. We voted for Perspectives, and Father Donelan accepted our choice.

The campaign against Invention was a turning point for me. It was the first time I had taken a public, leading role in a major campus protest. I did not regret this, though I did feel a bit disturbed about having burned books. Another council member pointed out that Hitler, in the 1930s, had stirred up the public with bonfires of books deemed poisonous to the ideals of Nazism. I was not sure if we had stepped over the line of legitimate protest into extremism and intolerance.

Before Ateneans went off for the Christmas break, KM-Ateneo, KKK, and Lakasdiwa picketed the Ateneo alumni homecoming luncheon at the plush Hilton Hotel, which we viewed as an ostentatious and crass display amid the country’s poverty and social turbulence. The alumni, in their fancy attire, driving up in their chauffeured, air conditioned cars, were greeted with placards, leaflets, boos, and taunts. One placard read: “Down from the hill, up to the Hilton!” It was quite a spectacle, though the alumni were not amused.

WHEN CLASSES RESUMED after the Christmas break, KKK, after months of soul-searching, had deserted the moderates and come over to the radicals. To coordinate efforts in our growing ranks, our three Ateneo radical groups established a loose confederation, the Makabayang Katipunan ng Ateneo (MKA) or Nationalist Confederation of Ateneo. I sat on the MKA council as one of the representatives of KM-Ateneo. We all immediately plunged into preparing for a rally to commemorate the first anniversary of the First Quarter Storm.

At that point, the government announced an increase in the price of gasoline. Drivers of public utility jeepneys went on strike and paralyzed jeepney services throughout Metro Manila. Denouncing the “imperialist” oil companies for “extracting superprofits” from Filipino consumers, activist groups joined the jeepney drivers in organizing a protest rally scheduled for January 13. The MKA, not bothering with a student council endorsement, mobilized a busload of Ateneo students. From different points of Metro Manila, the marchers—jeepney drivers, students, workers, slum dwellers, and vendors—converged on Plaza Miranda and over several hours cheered a battery of speakers. All of a sudden, we heard explosions—pillboxes, then gunshots. Armed Metrocom soldiers and policemen appeared from out of nowhere to break up the rally. I saw everyone around me running, but I could see no one from Ateneo. I sprinted down the Quiapo underpass and into a side street, and that was the end of my part in the rally. Later, I learned that four young demonstrators had been killed and over a hundred were injured.

Nationwide protests followed. MKA put up a red and black banner in the college quad in memory of the four dead demonstrators and hung effigies of Uncle Sam and Marcos from an acacia tree. We held successive teach-ins and discussion groups. On January 15, we mobilized 200 Ateneo students and jeepney and tricycle drivers for a short march within and around the university, stopping briefly at San Jose Seminary, the Loyola House of Studies, the dormitories, and the administration building and ending in front of the Loyola Center.

The anniversary of the First Quarter Storm was only days away and tension mounted throughout Metro Manila. Activist groups braced for another major confrontation with the police. A week before the scheduled January 25 commemorative rally, the moderate groups—NUSP, KASAPI, Lakasdiwa, the Federation of Free Farmers, and the Federation of Free Workers—changed their minds about joining and decided to hold an alternative rally two days ahead. They feared another outbreak of violence and the growing possibility that Marcos would use it as an excuse to declare martial law. NatDem radical groups stuck to their plans, scoffing at the moderates’ faint-heartedness. The Ateneo student council decided, by a close vote of 8–6 with one abstention, to join the January 23 rally and not to support the January 25 rally. But both rallies turned out to be peaceful.

Amid the hubbub over the violence at the January 13 rally and the threats of violence at the FQS anniversary rally, the issue of the oil price hike got somewhat sidelined. Gasoline prices were not rolled back.

BEFORE THE TENSION of the January events could subside, a new political storm broke out. Oil prices rose again, and jeepney drivers again went on strike. Activist groups once again denounced the greed of the oil multinationals and declared their support for the strike. The nation’s attention soon became riveted to UP Diliman, where students, led by the radical student council, protested the oil price hike by barricading all the main campus roads. As tempers flared, an irate professor shot and killed a student who was a former classmate of Jan (as recounted in Chapter 4). Student resistance broadened and hardened. Keeping police at bay, students took over parts of the campus, occupying university buildings and using the university radio station and printing press to denounce the government. This Diliman Commune held out for nine days, longer than the jeepney strike itself.

In Ateneo, the student council called for a boycott of classes on the first two days of the jeepney strike. However, only 150 or so students joined the boycott and marched down Katipunan Avenue to link up with striking jeepney drivers. On the third day, Ateneo’s activist groups took over. Gathering fallen tree branches, pieces of wood, old automobile tires, and large chunks of trash, we put up a barricade across Katipunan Avenue at Gate 3, blocking a public jeepney route. Soon, armed Metrocom soldiers and police arrived on the scene. We jeered, cursed, and ridiculed them. Tension built, until Fr. Joaquin Bernas, the dean of the college, and Rafael Chee Kee, the dean of students, intervened. The soldiers were allowed to remove the roadblock and then they departed, leaving the police behind. We rebuilt the barricade. Before long, several Volkswagen buggies and a truck arrived with more policemen. They charged at the barricade, firing their guns. Blanks? We weren’t sure. We scattered, most of us dashing through the university gate and into the grounds. However, some students fought back. Molotovs flew and the sound of pillboxes rent the air. Not much of a thrower, I didn’t join in hurling incendiaries. The policemen arrested 11 students, mauling one of them, a Lakasdiwa activist. After a few hours of detention at the police precinct, the 11 were released. The barricade went up again late in the afternoon and again briefly the next day. But the Metrocom and the police stayed away.

Compared to the 15-meter-high barricades in UP, which I saw when I visited the Diliman Commune on its last day, our Katipunan barricade was a minor affair, a puny obstacle that lasted for a brief period and attracted little attention in the dailies. It was, however, a signal event for Ateneo, the most dramatic and audacious protest action ever held in Loyola Heights. It heralded the rise of the NatDem radicals in Ateneo student politics.

THE MODERATE-RADICAL RIVALRY on campus heated up, with the approaching student council elections on February 19. For the first time, the NatDem camp contested more than a token number of seats. For our candidate for council president, we chose KKK activist and recent NatDem convert Alexander (Alex) Aquino, a seminarian and an academically outstanding junior, as well as a former sophomore representative. The moderates did not have a candidate from their own ranks, but they backed the candidacy of Teodoro (Ted) Baluyut, the chairman of the junior council. I ran again, for the second time that school year, to represent sophomores the following year.

During the election campaign, the campus came alive as it had not done in the past year—there were posters, banners, ribbons, leaflets, buttons, speeches, sloganeering, even campaign jingles. Nearly every Atenean seemed to be actively involved. Superficially, it was hard for a student to distinguish one candidate from another. As had previously been the practice, there were no announced party slates. Each candidate ostensibly ran on his own, with his own campaign machinery. The platforms all sounded the same, all calling, for instance, for Filipinization. However, everyone knew that the elections mainly pitted the moderates against the NatDem radicals and, in general, Ateneans knew who was who. Some moderates painted the radicals as rabble-rousers and violent extremists. To meet this red scare head-on, Alex admitted that he was a national democrat and that he would strive to build a “committed council.” Ted stressed that he was not aligned with any group and would see to it that the council remained a “free market of ideas.”

Unexpectedly for us, Alex won by a landslide. Almost everyone on our undeclared slate also made it. With the highest number of votes among soon-to-be sophomores, I automatically became chairman of the incoming sophomore council. Overall, NatDems were still a minority on the student council, but we were confident that we would be able to win nonaligned votes on important issues, and the moderates were in disarray. The triumph of NatDem radicals in Ateneo student politics resounded in many places. In the keen rivalry between moderate and radical groups for dominance on Metro Manila campuses and across the country, the radicals had scored a stunning victory. Ateneo was the home turf and the supposed bastion of the moderates, particularly the SocDems. Yet, they had been trounced.

THE SETBACKS SUFFERED by the Ateneo moderates must have dismayed and deeply embarrassed the Jesuits. Moderate activism was closely identified with them—most of the major moderate activist groups in the country had been organized by Jesuits or persons trained by them. On the whole, the Jesuits espoused social reform but were strongly opposed to violence and revolution. Thus, the radicals’ advocacy of armed struggle, even if covert, must have alarmed them, as must have the radicals’ espousal of communist ideology, seen as totalitarian and antireligion. Furthermore, radical activism was developing into a threat to the Ateneo itself. In their view, radicals were manipulating such issues as Filipinization and resorting to extreme forms of protest that disturbed the campus and disrupted the university’s academic mission. Unchecked, radicals could undermine the Ateneo’s Catholic and liberal leanings and destroy it as an institution of learning.

Ateneo students attend to their barricade in front of the university’s Gate 3 during a protest against campus repression (1971). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

When the Filipinization movement started in Ateneo, the Jesuits were divided, with the American Jesuits in general opposing it and the Filipino Jesuits supporting it to some degree, though not really challenging Ateneo’s overall Western orientation. As criticism became more strident during my first year, with the rejection of the path of social reform, the Jesuits put aside their differences regarding Filipinization and banded together in defense of their educational system.

As early as September 1970, Fr. Francisco Araneta, then newly installed as rector and president of Ateneo, declared: “Academic freedom cannot be absolute. No living organism allows without a struggle those forces which would destroy it to remain within the body. The university likewise cannot allow forces that are destructive of the university and of the total community to remain in the body. At one point it must make a stand.”

Few students paid much heed to those words, which were belied by the administration’s tolerance of leftist views and leniency toward radical militants. Before and after this declaration, we were able to speak out and publish virtually anything without being censored or harassed. From time to time, Dean Chee Kee did take down unsigned activist statements posted on the SOB (the student opinion board) and reminded activist leaders in the quad to switch off their sound systems or give up their megaphones when classes were in session. He warned that anyone disturbing classes was liable to be disciplined, but no one was actually sanctioned. Activists, including myself, were several times called to his office or that of Father Bernas, but the most that we got was a light oral reprimand never committed to paper.

Similarly, at the dorms, the proctors left radicals to themselves as long as they followed dorm rules. The only exception may have been my physics teacher, Fr. Francisco Glover, who stayed in Cervini. Jolly and friendly toward me when we first met, he took to needling me as well as other radical students: “If you don’t like Ateneo’s system of education, then get out of it.” When we had a chat once, he gibed, “Ateneo has given you a dormitory scholarship, why do you keep attacking it?” He cut off any reply by saying it was pointless to discuss further.

Toward the end of the school year, a more unified, harder line against campus radicalism became visible. When Father Bernas announced that he would not continue as dean of the college, Father Araneta picked Fr. Jose Cruz, an assistant professor of philosophy, to replace him despite strong objections from students and faculty. A tough disciplinarian when he was principal of the Ateneo High School, Father Cruz was controversial as a philosophy teacher. Known to be a personal friend of the Marcos family, he appalled many upperclassmen who took his courses with what they viewed as his apologetics for Marcos in class.

Close on the heels of Father Cruz’s appointment was the dismissal of two leftist faculty members. Dr. Dante Simbulan, associate professor of political science, and Adolfo de Guzman, mathematics instructor, were both NatDems and members of Malayang Guro ng Ateneo (MAGAT), to which my brother Norman also belonged. De Guzman, in addition, was chairman of the Ateneo chapter of the NatDem Samahan ng Makabansang Siyentipiko. When final exams started, they were informed that their teaching contracts, due to expire in four days, would not be renewed.

The new student council, which now referred to itself by its Filipino name, Sanggunian ng mga Mag-aaral, asked for the reasons for the dismissal of the two teachers, which Father Araneta refused to disclose, claiming that the proceedings of the committee on rank and tenure were confidential. Approached by Simbulan, however, he cited such reasons as poor teaching ability and irregular office hours. This was unconvincing since both teachers had been favorably evaluated by their respective department chairmen and had already been assigned teaching loads for the next semester. The political science staff attested that Simbulan kept regular office hours.

The Sanggunian could see no plausible reason why Simbulan and de Guzman were sacked other than their left-wing politics. Like other campus activists, I was astonished that the ax had fallen not on leading student activists but on two teachers who had played no direct role in campus protests. Greatly disturbed, a week after the dismissals, the Sanggunian wrote an open letter decrying them as arbitrary, unjust, and an infringement on academic freedom. We demanded the immediate reinstatement of the two. It was too late, however, to mobilize a student protest since summer vacation had begun. We received no response from the administration, but we did not intend to let the matter die.

SUMMER VACATION 1971 was not a rest period for activist groups. The moderates busied themselves preparing for mass actions linked to the inauguration of the Con-Con on June 1. KKK, having moved to the NatDem camp, went further and dissolved itself so its members, led by Sangunnian chair Alex Aquino and fellow seminarian William (Bill) Begg, could join KM-Ateneo en masse. The Sanggunian, now closely coordinating with the NatDem groups, set up a Nationalist Corps as a volunteer brigade to promote the political and cultural renovation of the Ateneo. Over a hundred students enlisted. Their initial assignment was to attend summer seminars for politicization, for which the corps put out a pamphlet, Basic Readings in Nationalism. While summer classes were starting, units of the corps headed to the provinces of Bataan and Quezon in a “learn from the masses” program of “integration” with peasants—to learn from, identify with, and politicize them. Within Ateneo, the corps also cultivated ties with the maintenance staff, sponsoring an activist play with a political message. I signed up for the corps but was able to attend only a few sessions of the summer seminars and could not participate in the integration exercise. I could not afford to commute to Ateneo often, much less travel outside Manila. Since I did not have classes in the summertime, I received very little pocket money from Dad.

The administration was also active that summer. We learned that a student activist from Ateneo High School had been denied admission to the college of arts and sciences and that two Ateneo workers had been dismissed on short notice. We also received a report that two American Jesuits tore down protest posters on the Simbulan–de Guzman issue late one night. The Sanggunian issued a manifesto protesting “the systematic suppression of progressive political views and activities” and the “autocratic structures” in the university, accusing the administration of “clerico-fascism.”

The term was soon to become a byword on campus, appearing on leaflets, SOB statements, posters, and graffiti on building and toilet walls. It popped up in speeches and newspaper articles. In a statement titled “Dissent and Clerico-fascism,” MAGAT attacked “the covert use—by a priest or a nun—of power that has accrued to administrative position by virtue of the paraphernalia of the religious life hitherto associated with otherworldly affairs, in order to suppress any movement for radical change within sectarian educational institutions.” MAGAT declared: “To expose clerico-fascism is a service to intellectual freedom.”

Girding for what appeared to be an upcoming confrontation with the administration on the Simbulan–de Guzman case in the coming school year, the Sanggunian, together with NatDem activist groups and some workers and teachers, held a small protest march on campus.

TOWARD THE END of summer classes, the Sanggunian, radical activists, and some moderate groups resolved to call for a general and indefinite boycott of classes beginning on July 9, the first day of the semester. We tried to keep the decision under wraps, but our feverish activity could not hide the fact that something was afoot. A few days before July 9, the officers of the alumni association, who usually did not involve themselves in student affairs, requested a meeting with the Sanggunian to discuss controversies on campus. After hearing us out, they urged dialogue with the administration before any drastic action was taken. But they were too late.

Early on July 9, we set up a picket in front of Gate 3 to announce the boycott. On campus, the first issue of Pandayan (a Filipino term meaning “anvil” and the new name of the Guidon) was distributed, carrying as its headline story the Simbulan–de Guzman case. At around 10 o’clock in the morning, the Sanggunian set up a microphone in the college quad and called upon students to boycott classes until the administration reinstated Simbulan and de Guzman. With calls of “Boycott! Boycott!” Sanggunian members and activist leaders, myself included, took turns lambasting the administration. Apart from the Simbulan–de Guzman dismissal, other student complaints, such as the increase in tuition and the lack of progress in Filipinization, were voiced. Activists fanned out to different classrooms to appeal to wavering students to heed the boycott. Within less than an hour, however, it became apparent that the boycott wasn’t holding—over half of the students were in class. The boycott fizzled out.

Ateneans then got a taste of how tough Father Cruz would be. The next day, the parents of seven student leaders received telegrams asking them to come for a talk regarding the possible expulsion of their sons. The seven were leading members of the Sanggunian, including its president Alex Aquino, vice-president Mario Jalandoni, senior council chairman and SDK activist Jonathan (Jonat) de la Cruz and junior representative Brigido (Jun) Simon Jr., Pandayan editor Manolet Dayrit, Nationalist Corps chairman and leading KM activist Bill Begg, and SDK militant Michael (Mike) Molina. They were charged with “preventing or threatening students or faculty members from discharging duties or attending classes.” Through a stroke of luck, I was not included among them. The bell for the class break had rung when it was my turn to take the microphone, so technically I did not disrupt classes.

“The original act of injustice is now being compounded with new acts of injustice. And so I must speak.” Dr. Bienvenido Lumbera, the highly respected chairman of the Philippine Studies Program and a member of the committee on rank and tenure, addressed these words to a packed convocation of students and teachers in the cafeteria. Breaking the seal of secrecy of the committee, he revealed that they had not recommended terminating the contracts of Simbulan and de Guzman. They had indeed denied Simbulan tenure, and his political views had figured prominently in this decision. In being dismissed, however, the two had been “victims of Father Araneta’s undue haste in dispensing with their services.” Himself a MAGAT member, Lumbera was convinced that the dismissals had been due to their leftist political views. He charged, “There seem to be elements in the academic community who are reluctant to declare themselves openly against the national democratic movement, but are ready to lend a hidden hand in counteracting it.”

The next day, the Sanggunian called for another boycott of classes, adding the harassment of student leaders to its list of issues. The atmosphere was tense and somewhat intimidating, as the prospect of further disciplinary actions for disrupting classes hung in the air. Relatively few students boycotted, but those who did were highly fired up. After an overcharged teach-in in the main corridor, we burned the effigies of Father Araneta and Father Cruz in the quad. Then about a hundred students marched toward the administration building shouting, “Ibagsak ang kleriko-pasismo! (Down with clerico-fascism!)” Pillboxes exploded nearby. We bounded up the stairs of the building to demand an audience with Father Araneta. The glass doors were locked. Those in front pounded on the doors with their fists until the glass shattered, pieces falling around us. Startled, we retreated back down the stairs and hastily dispersed. It dawned on me a few minutes later, safely away from the scene, that, without planning to, we could have occupied the building and barged into Father Araneta’s office. Instead, our protest lay in shards.

THE ADMINISTRATION HELD firm. Simbulan and de Guzman were not reinstated, and disciplinary proceedings went ahead against the seven student leaders. Moreover, the administration banned convocations in the cafeteria, confining them to the quad or the out-of-the-way fourth-floor auditorium. It was clear to me that the Araneta-Cruz tandem was grimly determined to stamp out radical activism on campus. Students seldom saw either of them on the college grounds. They entrusted much of the work of maintaining order to the new dean of students, Hilarion Vergara. Vergara was a contrast to the youthful and hefty previous dean, Rafael Chee Kee. He was elderly, bespectacled, and deceptively frail-looking, and he had earned a reputation as a stern prefect of discipline at Ateneo High School under Father Cruz. Dean Vergara was an assiduous watchdog. At every protest, or even when one was still being planned, he was always around, observing, listening, taking mental notes, and from time to time, like a padre de familia, warning or reproving student militants.

Ateneo students and workers protest the “death of academic freedom” in a march on campus following the dismissal of two progressive faculty members. Nathan (fourth from left) helps carry a mock coffin with the words “Durugin ang kleriko-pasismo (Crush clerico-fascism)” (1971). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

I began to feel uneasy about my situation in school. The threat to expel the seven had unnerved me. In the weeks that followed, I wavered about whether I should be at the forefront of protest actions. I decided I had to continue with political activism, but that I should also play it safe, keeping as much as possible within the bounds of university regulations. I could not risk disciplinary action, which would mean losing my scholarship and possibly any chance of getting a university degree.

WHILE THE SCHOOL administration was monitoring radical students, it was not sensitive to trouble developing elsewhere. For a few months, trade union organizers belonging to the radical Katipunan ng mga Samahan ng Manggagawa (KASAMA) or Federation of Workers’ Associations had been conducting politicization seminars among Ateneo’s maintenance personnel. The organizers were led by Alan Pobre, a classmate of mine who had dropped out of school to become a “full-timer” who devoted all his time to working for the movement. In mid-May, the union local left the moderate Jesuit-influenced Federation of Free Workers to create a new union affiliated with the more militant KASAMA. They drafted a list of demands, including recognition of their union, reinstatement of the two dismissed workers, a three-percent wage increase, and the release of previously collected union and life insurance dues. The administration rejected the demands, and conciliation attempts by a representative of the Department of Labor failed. On August 20, the workers voted to strike and contacted the Sanggunian to ask for our support. They set the beginning of the strike for three days later, on August 23.

Before the strike could begin, national politics took a dramatic and gruesome turn. On August 21, 1971, at Plaza Miranda in downtown Manila, unknown persons threw live grenades on the stage during the final campaign rally of the Liberal Party, the main opposition party, before the senatorial and local elections. Nine people were killed and scores wounded. Among those seriously injured were opposition senators Jovito Salonga, Gerardo Roxas, and Sergio Osmeña Jr., and Manila mayoral candidate Ramon Bagatsing. Marcos immediately pinned the blame on the Communist Party of the Philippines, charging that it was trying to sow chaos and discord in furtherance of its plan to overthrow the government.

I was stunned by the news of the bombing. How on earth could anyone plan and perpetrate such a despicable act? It could have been worse. If the grenades had exploded in the middle of the crowd, scores more could have been killed. A few feet closer to the stage, they could have wiped out virtually the entire leadership of the Liberal Party. I instantly dismissed Marcos’s allegations that the CPP was behind the bombing. Like many kasama, I thought it probable that Marcos himself had instigated the dastardly act to provide an excuse for staying in power. A sense of foreboding came over me.

Despite the dark clouds on the political horizon, the Ateneo workers launched their strike on August 23 as planned. The university administration was taken by surprise. The Sanggunian passed a resolution in support of the strike; radical activist groups came out in full force to join the striking workers at the picket sites. We helped with mobile pickets in front of all three gates of Ateneo. Classes from grade school to college were suspended.

It was my initial first-hand experience of a workers’ strike. Together with other student activists, I tried my best to support the workers and, in the process, befriend them. We helped pitch tents and cooked and ate with them. We spent time talking and sharing experiences, asking them about their families and their working and living conditions, cracking jokes, and singing along with them. We formed discussion groups and taught the workers revolutionary songs. To raise funds for the strike, we asked for donations from fellow students, commuters, and passersby. Sympathetic jeepney drivers slowed down their vehicles to allow us to solicit contributions from passengers. I helped write and produce statements and press releases about the strike.

About 50,000 people assembled for a “people’s congress” organized by the Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties at Plaza Miranda (September 13, 1971). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

That evening, after delivering press releases to various newspaper offices in downtown Manila, I learned from other kasama that the writ of habeas corpus had been suspended throughout the country. They had just heard the news over the radio. In Proclamation 889, Marcos also ordered the arrest of leaders of radical organizations, which he branded as subversive communist fronts. I had to ask others what suspension of the writ meant: that a prisoner could no longer be guaranteed an appearance before a court to challenge the legality of his or her detention. Marcos said he had suspended the writ within a few hours of the Plaza Miranda bombing. It occurred to me that we had been picketing the whole day without knowing that, with the writ already suspended, we could all have been picked up by the police and indefinitely detained.

Nevertheless, the strike continued. Some student activists stayed overnight with the workers to man the picket. I didn’t join them and instead slept at Cervini. I was worried about a sudden raid by the police or the military and also unsure whether I could endure the hardship of sleeping in a tent or in the open, without pillows and blankets, side by side with workers and other activists who were dusty and grimy from a day at the picket. The next morning, I was back there with other student activists. We wrote statements condemning the writ suspension and the growing repression in the country. We prepared papeldikit (posters) to put up in the nearby town of Marikina, daubing slogans in red paint on old newspapers. All day we felt anxious, half-expecting truckloads of men in khaki or fatigues to arrive suddenly. But nothing happened.

Virtually all sectors of Philippine society condemned the Plaza Miranda bombing. The writ suspension was also very widely denounced by radicals and moderate activists, progressive Con-Con delegates, prominent political opposition figures, civil libertarians, respected newspaper editors and columnists, and other opinion leaders. Civil libertarians headed by Sen. Jose W. Diokno saw the writ suspension as a dangerous move that was bound to lead to further suppression of civil liberties. The CPP and radical activist groups went further, accusing Marcos of masterminding the bombing himself. The CPP asserted that Marcos was plotting to perpetuate himself in power in a one-man dictatorship, and that the Plaza Miranda bombing was a part of the plot, meant to justify the imposition of repressive laws and measures.2 The CPP warned that the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus was a prelude to the declaration of martial law.

THAT EVENING, AFTER supper at Cervini, I drove out to Marikina with three fellow KM activists—Bill Begg, Kiko Villanueva, and Danny Nicolas. With our papeldikit, we brought along pails of homemade paste, starch dissolved in boiling water. We put up our papeldikit every few hundred meters along Marikina’s major roads and thoroughfares, on lampposts and walls, regardless of signs warning “Post no bill,” but always on the lookout for patrolling police or military vehicles. We were almost done when a police jeep passed. The police had seen us! We rushed into the car and Bill stepped on the gas. We needn’t have bothered. Bill’s rickety, dirty white station wagon was no match for the brand new police vehicle. We were caught red-handed, with a messy, sticky mixture of red paint, black newsprint ink, and paste on our hands.

At a police station near Marikina’s town hall, we were booked for malicious mischief, photographed, and made to “play the piano”—activist slang for having fingerprints taken. The police interrogated us without bothering to inform us of our rights. Bill—intense, indefatigable, and sometimes brash—kept answering their queries insolently, and one of them punched him in the stomach. However, when they learned that we were Ateneo students, they began treating us with kid gloves and allowed us to phone our parents, friends, or lawyers for help. None of us wanted to phone our parents; I didn’t dare call Dad. Instead we called friends at the Ateneo who were not too closely identified with activism and who we knew had connections in high places. They arrived shortly and assured us that they were doing what they could to get us out quickly. But we still had to spend the night in a small jail cell, where we hardly slept.

The next morning, we were brought before a judge in a small courtroom nearby. There were few people around and the judge called us up immediately. In a low voice, he admonished us and advised us not to commit such a misdemeanor again. Then he let us go and all charges were later dropped.

We may have been among the first political activists apprehended after the writ suspension. During this period, scores of activists were rounded up, mostly in military raids on the headquarters of activist organizations. We were lucky to have been released from detention quickly. Of course, the four of us were just ordinary activists, not leaders of national organizations, and not on the military’s “wanted” list. But many other ordinary activists picked up spent days or weeks in jail. The well-known personalities caught in the military’s net, such as KM secretary-general Luzvimindo David and Movement for a Democratic Philippines spokesman Gary Olivar, suffered much worse fates—months and months in detention. We got off lightly, though there was more fallout to come.

THOUGH THE ATENEO workers tried to continue their strike, the writ suspension eventually proved disastrous. We had counted on the total disruption of classes, but with reports of military raids and the arrest of activists, apprehension and uncertainty spread among the strikers and their supporters and the numbers on the picket dwindled. Funds collected for the strike were reduced to a trickle. The strike was losing its force.

The workers ended their strike on September 1. In the return-to-work agreement, the Ateneo administration agreed to reinstate one of the dismissed workers and submit to voluntary arbitration on a wage increase. They also agreed to release the workers’ union and life insurance dues but without formally recognizing the workers’ union and its affiliation with KASAMA. The workers and their supporters tried to put on a cheerful face, but we all knew that the nine-day strike had accomplished little, much less than we had confidently expected at the start.

IN PROTEST OVER the writ suspension and the heightening repression, a new nationwide coalition headed by Senator Diokno was formed. The Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties (MCCCL) consisted of a very broad array of groups and personalities—moderate and radical activist groups of youth and students, workers’ federations, peasant organizations, urban poor associations, women’s groups, organizations of teachers, artists, lawyers and other professionals, religious groups and personalities, civil libertarians, progressive Con-Con delegates, and a few politicians. For the first time, NatDem and SocDem groups, as well as groups aligned with the pro-Soviet PKP, got together under a single umbrella. The MCCCL staged rally upon rally, calling for the lifting of the writ suspension and the release of all political prisoners and vowing to resist any plan of Marcos to impose martial law. Meanwhile, at the Con-Con, 22 delegates filed a resolution prohibiting the extension of the President’s term. Marcos castigated the move as being “personally motivated by hate and self-interest.”

The Sanggunian vigorously supported the MCCCL. It invited two progressive Con-Con delegates, Voltaire Garcia and Romeo Capulong, to explain the implications of the writ suspension to students. It mobilized 300 Ateneo students for MCCCL’s 50,000-strong People’s Congress for Civil Liberties on September 13 at Plaza Miranda. The MKA appealed to all the sectors of the Ateneo community—students, teachers, workers, and the administration—to put aside differences and unite against “the wave of fascism led by the U.S.-Marcos alliance.” The Sanggunian sponsored a rally for all sectors of the university, with Con-Con delegates Jose Mari Velez and Fr. Pacifico Ortiz (former rector-president of the Ateneo), faculty member Dr. Lumbera, and several student leaders as speakers.

A subsequent MCCCL protest march from Manila to Caloocan City on October 6 drew only 40 Ateneans, but it proved memorable to me. A rumor had spread that the mayor of Caloocan was sending out his armed goons to forcibly disperse the marchers, as he had done with two previous rallies. Despite this and the heavy rain, the march proceeded. At the forefront were Senator Diokno, Con-Con delegates Voltaire Garcia and Heherson Alvarez, and newspapermen Joaquin (Chino) Roces and Amando Doronila. Twice, a phalanx of armed men blocked our way, but we detoured. After walking a dozen or so kilometers braving the rain and strong winds, we entered Caloocan. The goons were gone.

While the other marchers chanted triumphantly and some practically danced on the street, I shivered under my raincoat. I had never felt so wet, cold, and tense. We had made great strides at the Ateneo, and here we were, still marching, but the forces of repression were closing in.

NOTES

1 In its literature in Filipino, the CPP also uses the initials PKP, but to avoid confusion it will be referred to here only as the CPP.

2 Since the fall of Marcos in 1986, a growing number of credible accounts have indicated that the Plaza Miranda bombing was perpetrated by leading CPP figures, principally party chairman Jose Maria Sison. Prominent among these accounts are those of former CPP Central Committee member Victor Corpus, bombing victim Sen. Jovito Salonga, American journalist Gregg Jones (Red Revolution: Inside the Philippine Guerrilla Movement, Westview Press, 1989), and UP Asian Center dean Mario Miclat (the novel Secrets of the Eighteen Mansions, Anvil Publishing, 2010). According to them, Sison and company plotted the bombing, convinced that it would exacerbate the conflicts within the ruling class and hasten the victory of the communist revolution. After the Corpus and Jones revelations, I asked some kasama in the CPP Central Committee about the Plaza Miranda bombing, and they confirmed to me that the two writers’ accounts were on the whole accurate. I eventually became convinced that the brains behind the bombing had indeed not been Marcos but Sison, though Sison has continued to deny this.