Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Christian’s Choice

7

NORMAN F. QUIMPO

WHEN THE STUDENT PROTESTS began in 1970, I was a 24-year-old assistant instructor in mathematics at the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University. Like many other teachers in school, I couldn’t resist straying from my usual classroom topics and discussing the “current crisis.” I had my share of leading discussion groups in classrooms or wherever else students wanted to talk, even in our apartment. I also spent time with a dozen like-minded teachers who sought to introduce nationalist concerns into the agenda of faculty meetings. We called ourselves the Malayang Guro ng Ateneo (MAGAT) or Free Teachers of Ateneo. We took upon ourselves the duty of questioning university policies we deemed reactionary. An American Jesuit was said to have branded us as the school’s “brown power” advocates.

My involvement with my co-teachers and students didn’t last for more than two semesters. The students I helped politicize (or who politicized me) soon moved on to various activist factions. At the end of the summer term 1971, our teachers’ group broke up after the school terminated the teaching contracts of two of our members. We were shocked by the dismissals. There was some furor when a member of the school’s Rank and Tenure Committee stated that the case of one of the teachers was tainted by anti-subversion politics. The protests faltered, however, soon after the new school year began. I had a feeling the members of MAGAT were dispirited and unable to pursue the nationalist agenda with the same enthusiasm as before. I thought too that the student interest in campus issues would soon peak. The students could only do so much boycotting of classes. They could then either force the school to close or to expel them. I went about my teaching duties and perceived no sign from school authorities that my own teaching contract was at risk. But I began to wonder if my energies could be better directed to concerns outside the campus.

MY REFORMIST HOPES had died with the 1969 presidential election when Marcos ran for a second term and won. That election saw the usual large-scale intimidation, vote buying, and ballot manipulation that have characterized all Philippine elections after 1945. The difference was that it happened at a crucial stage in my life—when I was at my first job and had high hopes of raising a family in a better economic and political environment. My wife, Bernie, and I had invested a lot of emotion in that election, rooting for the opposition Liberal Party (LP). We were convinced that the LP candidate, Sergio Osmeña Jr., had been cheated of victory.

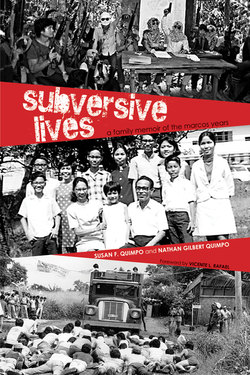

Norman joined the Ateneo faculty as assistant instructor in mathematics (1967). (Photo by Freddie Ileto)

On hindsight, I think that my feelings resonated with those of large sectors of the population. They were just as disgusted as I was with the economy, the election, and another four-year term for Marcos. The disaffected included a significant number of the youth—high school, college students, and young professionals. They felt the economic pinch. They heard their parents and elders blame the Marcos administration for all the ills of the country. They deemed that changing the government through elections was a hopeless endeavor. They believed, as I did, that a system that allowed such a corrupt regime to enjoy a second term was seriously flawed and needed a radical overhaul.

The FQS brought into the open new and exciting ideas about effecting a fundamental change in the system—ideas about revolution. Teachers and students all over the city read Renato Constantino, Hernando Abaya, and other nationalist writers. These authors wrote Philippine history from a viewpoint different from that espoused in standard textbooks that simply presented a chronological account of events in language that would have gratified any colonial censor. These nationalist writers talked about the invasion by foreign exploiters, a people’s subjugation and slavery, and the Filipinos’ attempts to throw off the foreign yoke, only to be repeatedly frustrated by force with the help of local collaborators.

These writers awakened in me a dormant patriotism. After all, our grade school teachers had raised us on anecdotes about Rizal, Mabini, Luna, and other heroes of the 1896 revolution. The new nationalist literature also reawakened in me a compassion I’ve always had for the common folk. Such feelings went back to my grade school days in Iloilo City, where half of my playmates were the children of rice mill workers. I came to understand that the lot of the common man had been hard in colonial times and remained so in the post-World War II period.

But while many young people, particularly students, were ready to pull out all the stops in their activism, like dropping out of school to become full-time organizers, my personality, background, and head-of-family status held me back. I was a cautious and nervous person. I was used to routine and did not easily adapt to new situations. I was excited by the prospect of change but also fearful that the status quo in Philippine society that I associated with my happy childhood would be upset.

I had been raised a “practicing Catholic.” My mother and her family were devout Catholics; my father’s family was devoutly Protestant, but he converted to Catholicism before marriage. I was steeped in a traditional Catholicism where on Good Friday one expected the whole town to join the procession for the dead Christ.

My Catholic upbringing was strengthened further by 10 years of schooling at Ateneo de Manila, a Jesuit school. Not only did the liberal brand of Catholicism the American Jesuits espoused resonate with me, I also came to appreciate the genuine concern the Jesuits I met showed for me.

The Jesuits built up virtues that my parents had started to instill in their children: a Christian commitment to truth, justice, and duty (that my Dad showed in pointing out the misdeeds of government officials), a passion for excellence (that Dad not only spoke about but also demonstrated in the manner he handled the jobs he accepted), and a concern for the less fortunate (that my Mom showed in helping relatives even poorer than we, indigent acquaintances who needed medical assistance, maids who were treated like family).

I WAS NOW on the lookout for an activist group that was radical but mindful of Christian principles. I examined the position papers, platforms, and manifestos of various activist groups and was quickly dissatisfied with the statements of those who called themselves Social Democrats or SocDems. To me, their formulations sounded imprecise, showed a poor knowledge of Philippine history and a lack of awareness of international politics. Their platform appeared to be the work of an elite few who did not touch base with the populace. I looked elsewhere for answers.

A couple of students from my discussion group in school joined the Malayang Pagkakaisa ng Kabataang Pilipino (MPKP) or Free Union of Filipino Youth, an affiliate of Jesus Lava’s Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas that led the Communist Hukbalahap guerrillas of the 1940s and 1950s. In the rallies that started at the Welcome Rotunda in Quezon City, I remember seeing workers and farmers, rather than students, gathering under MPKP banners near Blumentritt Street. What caught my eye, and that of most people watching on the sidelines, were the more numerous streamers following the red banners of Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK). These groups called themselves National Democrats or NatDems and were believed to be red-infiltrated. They stood out because of their numbers, their radical slogans, and their eagerness to confront the riot police.

KM and SDK branches appeared soon enough in Ateneo’s college and high school, but they were student organizations and I felt awkward about getting involved with them. I tried getting involved with NatDems at my level from outside Ateneo, but my encounters were disconcerting.

Before it dissolved, MAGAT organized a meeting in the one restaurant that then fronted Ateneo, to help teachers from St. Theresa’s College, a Catholic girls’ school, who were being fired. Some UP NatDems led by a young UP teacher asked to be allowed to attend the meeting as observers. By using aggressive language, these radicals managed to take over the meeting. The instructor even delivered a rousing speech to agitate everyone. Without looking closely into the teachers’ individual cases, the NatDems convinced them to start picketing the next day. The picketing fizzled out in a couple of days, but their firebrand advisers had disappeared by then.

I also had a brief stint with a small NatDem group of scientists and researchers based in UP that called itself the Samahan ng mga Makabansang Siyentipiko (SMS) or Association of Patriotic Scientists. The group coalesced around Roger Posadas, the leading light of the UP Physics Department. Joining such a circle of activists with a science stamp to it seemed natural since I was doing mathematics. After joining a few of their study sessions, however, I dropped out. I was not able to relate to the unstructured meetings that wandered from commentaries on dialectical materialist principles to such practical matters as the preparation of a more powerful “pillbox” (homemade bomb) for the self-defense of fellow activists.

The National Democrats appeared fearsome to Catholic school students and teachers, yet they posed a great attraction. They were the radicals in the protest movement. The gospel they preached, namely, a national democratic revolution supported by people’s war and led by a new Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), presented a dilemma to people like me. So impressed were my parents with Americans and the American way of life that they named me after an American GI, a Texas oil millionaire who had become a close family friend during WWII. They had fond hopes that my siblings and I would someday find our way to the United States and pursue the American dream. How could I get involved with a movement that was communist-inspired? Stories I had read about communists in my younger days still horrified me, stories of Joseph Stalin’s bloody pogroms and purges and graphic references to communist persecution of Christians. How could I get involved with a movement with a godless ideology that ate Christians for breakfast?

AS THE MONTHS PASSED and the national crisis deepened, it appeared increasingly urgent for an activist like myself to be part of a political organization with a winning strategy. I needed a push, and a priest provided it: Fr. Edicio de la Torre, SVD. His following was growing among priests, nuns, and seminarians because of his lucid essays and lectures about politics from a Catholic viewpoint. I could relate to his arguments. His revelatory essay, “Christians in the National Democratic Revolution,” provided reassurance that radical involvement was justified, as liberation theology argued, in order to bring about God’s kingdom on earth.

I read him and wanted to hear him speak. I made it a point to attend when he came to give a talk at Ateneo. The audience in the main biology lecture room was abuzz with anticipation. When Father Ed began, his words about Christian involvement in the struggle were a refreshing breeze. He showed that deeply felt anger against injustice and compassion for the oppressed was rooted in the Catholic faith. But what sticks most in my mind was how he challenged the audience, made up mainly of the middle class and petit bourgeois. One cannot be sure, he said, that people like you will remain faithful to the cause of radical change, much less provide resolute leadership in the struggle. The middle class was marked by two failings: “mahina ang tuhod at malabo ang isip (weak in the knees and confused in thinking).”

He promptly dismissed fears of the communists. The time to join the struggle for national liberation was now, he said, to muster more forces and enrich the variety of the united front. The NatDem program was a political program to get control of government. As a Christian, one could accept it without becoming a communist. Would a red regime later turn against and oppress the Church? One had to postpone such worries; being part of the struggle would provide some insurance against being attacked as a reactionary force, though one always needed to be vigilant about one’s faith.

What about the use of violence and the talk of people’s war? It took time for me to realize that this was no big deal. The issue was often raised in a classroom, coffee shop, or beerhouse, but that was taking it out of context. In the streets in 1970, the question could not be pondered in an academic way. If you participated in the parliament of the streets, sooner or later you would be involved in a bloody confrontation with the police. And if Manila was a battleground, in the countryside there simmered a continuing, if undeclared, class war.

This war was an extension of centuries of agrarian conflict. Peasants fighting for land rights, or lower rent, or simply against eviction, have been confronted by landowners and their allies or hirelings: local governments, local police, the courts, the Philippine Constabulary, hired thugs, private armies, even other farm workers who had been bought off. Who could cite a case where courts, sheriffs, policemen, or militia went out of their way to support a peasant’s grievance? Do you wish to organize peasants to help them win concessions? Then you can be certain that your work at some point will be met with violence.

The middle classes heard about confrontations between landowners and tenants on one or two specific estates but were shielded from the full scope of the violence. We should not have been asking, “Shouldn’t Christians turn their backs on violence?” but rather, “As Christians, you’re called to do your share in uplifting the sad lot of the poor and the oppressed. If you decide to go—out of your usual way—to help them, are you prepared to defend yourself and them?”1

THOUGH MY FEARS of the NatDems were fading, I did not want to join KM or SDK. They were still too red for me. Even with a KM member living in our apartment, my own brother Jan, I was in awe of them, seeing them as battalions of communist organizers seasoned by labor struggles.

Thus, when I heard of some activist Protestants who were friends of Father Ed, I did not think twice about meeting them. Some of us in Catholic schools might have hesitated to work with Protestants, but it was only a fleeting obstacle for me. My father’s siblings were all Protestants; I had spent my childhood years in the neighborhood of Central Philippine University, founded by Protestant missionaries, and my best friend came from a devout Protestant family.

At the office of the Student Christian Movement of the Philippines, the local chapter of an international youth organization affiliated with the World Council of Churches, I met Jurgette Honculada, Bernie’s friend from her days as a campus editor. It was just the right time to connect with this organization. An ecumenical group of its members, including Father Ed, Carlos (Caloy) Tayag, Elmer,2 and some others, had begun to realign it to join the activist mainstream. A significant step they took was to change the name of the organization to the Tagalog translation of the original: Kilusang Kristiyano ng Kabataang Pilipino (3KP).

I was surprised to discover how far ahead of Catholics local Protestants were in considering questions of faith and politics and translating their conclusions into action. They had been exposed to the ideas of liberation theology, imported from Latin America, long before Catholic religious in the Philippines heard about it. Chapters of the Student Christian Movement in Latin America had been deeply involved with victims of the repressive military governments of the time, and some of their members were being hunted by the military. There was no interest in liberation theology in other quarters in the Philippines until the 1970 student protests.

I had met Jurgette’s husband, Ibarra (Bong) Malonzo, who was also part of the ecumenical group, in 1966 at the Silliman University Summer Writers Workshop. Bong was in Dumaguete to do work for KM (as I learned later) and wandered into an early session of our workshop, the event of the summer at the university, to see if he could get into some stimulating discussion on global political issues, such as the Bomb and the danger of nuclear winter. However, we workshop fellows were remarkably naïve about world affairs; we were concerned only with the structure of poems and the plots of short stories.

When I met Bong again at the organization that was to become 3KP, I was awed by the depth of his and Jurgette’s experience and theological commitment. They explored the Christian-Marxist dialogue in earnest and were living their lives according to their beliefs. Apart from being an early KM member, Bong had experienced working with unions—his father was a veteran labor leader. He had been beaten by police at a picket and had spent time in jail. It was enough to convince me to join their organization.

Since there were few warm bodies around at the start of the reorganization, I was put in charge of the education department. We drew up a curriculum for new members, including readings and discussions of Renato Constantino’s essays, SND, and articles on liberation theology. We started a newsletter called Breakthrough, which Jurgette edited expertly. One of the articles it carried, a primer on liberation theology by the Peruvian theologian Gustavo Gutierrez, was my constant companion in the days that followed. Breakthrough offered its readers an activist perspective. It published, more than a year before martial law, Pastor Niemoeller’s prophetic warning to German Christians during the rise of the Nazis: not to turn a blind eye to the persecution of Jews, gypsies, and other minorities, before the regime turned to persecuting Christians.

Breakthrough carried in one of its first issues a Biblical passage that I thought best summed up the motives of the 3KP activists. These were the opening lines of Isaiah 61, read by Jesus at the synagogue in Bethlehem at the start of his public ministry:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

Because he has anointed me to bring glad tidings to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim liberty to captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free.

And to proclaim a year acceptable to the Lord.

3KP proclaimed our NatDem credentials in an exchange with the SocDems carried in the UP campus paper, the Philippine Collegian. The SocDems had published a long article about the national crisis and their program for change. We formulated a point-by-point rebuttal that the Collegian also carried. We pointed out that the Church had been a reactionary force in Philippine history, always protective of the establishment. It could not lay claim to a preeminent position in the struggle for change. We observed also that the SocDems appeared more interested in derailing the revolutionary movement than in seeking fundamental societal change.

The SocDems responded with another article that denounced 3KP, as well as Christians for National Liberation (CNL)—an organization of NatDem priests, nuns, ministers, pastors, and lay religious workers—as constituting a communist Trojan horse that attempted to disguise the NatDem program as an allowable Christian choice. The article warned that the reds might appear welcoming now but would eventually turn on Christians and suppress them as a reactionary force. I thought the accusations unjust. They did not credit the difficult choice 3KP members had made in “fear and trembling,” they did not recognize that Christians would always have to fight for their beliefs in whatever society emerged, and they rejected dialogue in favor of preaching about the correct party line for Christians. Whether or not we won that exchange with the SocDems, the banner of 3KP was now flying.

Norman (seated extreme left) first met Bong Malonzo of the SCM at a writers’ workshop in 1966. Bong could not interest the participants in a discussion of socio-political issues, of which they had little knowledge.

IN THE SHORT PERIOD from its reorganization in 1971, the SCM was able to participate in the three main activities of NatDems in the city—protest mass action, support of workers’ strikes, and “integration with the masses.”

I joined practically all the major rallies of 1970 and 1971, first as an unattached angry citizen, then later as a member of 3KP. Bernie joined me in several of the rallies. The one she remembers best is the Good Friday march of 1972 sponsored by the Movement for a Democratic Philippines, the umbrella organization for all NatDem groups. Lent, Good Friday in particular, is a high point of Catholic religious ceremony in the Philippines, so CNL and 3KP were expected to play a big role in this rally. I remember the huge banner we carried that day—a squarish panel of katsa (rough cotton cloth) that loomed like a sail. Painted on it was a cross borne by the people—the three evils of imperialism, feudalism, and bureaucrat capitalism. Below the picture were the words, “Ibaling ang pagdadalamhati sa rebolusyonaryong katapangan (Turn grief into revolutionary courage).” The central character painted on the canvas was a Filipino Thor, a muscular worker striking forward with a hammer, sending a collection of dubious characters in coat, tie, and top hat and in barong tagalog scrambling back in fear.

I missed attending a major rally with 3KP because I had elected not to be absent from my classes that day. It was the one MDP organized for Caloocan City, the exit from Manila to the northern provinces. The demonstrators were to assemble at the usual places in Manila, march through Rizal Avenue and mass at the Balintawak Monument (a landmark dedicated to the 1896 revolutionary leader Andres Bonifacio and his men at the Caloocan Rotunda). The march started in downtown Manila but never quite reached the Bonifacio Monument. At the Caloocan boundary, it was brutally attacked by goons and thugs said to have been hired from the extensive squatter colonies of the city by Mayor Macario Asistio, a staunch ally of Marcos. A newspaper photograph of that time shows a fearsome mob armed with pipes, 2-by-2s, knives, and even sickles, blocking a street. The marchers had to disperse after being rushed by such armed groups. I heard about the bloody aftermath of the rally from 3KP member Sonny Hizon, who used his Ford Escort to carry wounded demonstrators to nearby hospitals.

The one occasion when 3KP members were able to give direct support to workers was when we joined striking workers picketing at the Atlas factory in Novaliches, an industrial zone on the outskirts of Manila. When I got to the large vacant lot in front of the factory, a group of about 30—some workers and 3KP activists—had gathered near the entrance. The person chosen to express our support for the strike, an ex-seminarian named Rey, was delivering his speech. Suddenly, a jeepload of policemen arrived. They closed up in a rough line to within a dozen meters and stood there menacingly as Rey was getting to the high point of his speech. He had his fist raised and was shouting, “At ano kung harapin nila tayo ng karahasan? (And what if they confront us with violence?)” He was referring vaguely to the state, not to this group of policemen specifically. Everyone waited nervously for his answer to his own question, seeing that the policemen were within hearing distance. The tension was palpable. He continued weakly, “Eh di kausapin natin sila. (Oh then we reason out with them.)” That was the end of his speech and the small crowd quietly dispersed, we 3KP members slinking away with all the dignity we could muster. When we had put some distance between ourselves and the policemen, we broke out in laughter, slapping Rey on the back and teasing him about his tough words.

The leadership of 3KP felt that sooner or later we would have to do organizing work among the masses. This required that we first learn how to analyze the situation in a community. We had to practice conducting what was called by activists a “social investigation” or “SI.” The term used was derived from Mao’s essay, “On Social Investigation,” the principal guide of NatDem activists on the analysis of the differing social classes. A team of activists would survey a community, determine the social classes present there, and detail the dynamics between these classes. The team would then have basic data on who may be sympathetic to, and who may oppose, revolutionary change.

We set out to do our first SI near a Philippine Army camp in Bicutan, a town south of Manila. Yes, we knew the exercise would also give our members a chance to “integrate” or express solidarity with the poor in the area. But beyond that, we felt we had taken a significant step in the journey to the countryside and people’s war.

None of us had any experience in this kind of activity. In preparation, we had studied Mao’s article and obtained copies of some guidelines from another NatDem organization. I approached the project with some hesitance. Going out to talk to the residents of an urban poor community was novel and strange to a petty bourgeois intellectual like myself. Moreover, I was a shy person and doing SI meant I would be going out of my way to talk to strangers, in Tagalog, that I, an Ilonggo, was ill at ease with. But my comrades and I threw ourselves into the spirit of the exercise and quickly became absorbed in the details of the operation.

The area was government land so everyone who lived there was technically a squatter. We divided up the area into sections, assigned a pair of activists to each section, and fanned out. This way, we were able to interview almost all the residents of the area.

It was not easy figuring out who was who among the settlers. Who was oppressor and who was oppressed? Practically all of those we interviewed seemed to be oppressed. They all had the same problem, namely, keeping their heads above water economically. Later, back at the headquarters, we argued about who was a worker, a member of the petty bourgeoisie, a capitalist, a member of the lumpen proletariat (society’s undesirables), etc. Our preconceived notions of who was an ally or who was an enemy of radical change were often overturned by the results of the interviews. For example, we met soldiers who were employed by the state and therefore should have been defenders of it. But they too were oppressed, confiding to us their fear of being evicted from their homes at any time.

WORKING WITH PROTESTANTS took me to various places where few Catholics tread. We held a number of study sessions at the Hugh Wilson Ladies Hall on Lerma Street, a kind of YWCA center. There I discovered that several of our Protestant 3KP members were DeMolay members, that is, Junior Masons. Filipino Catholics have always been warned by church authorities against consorting with Masons. The Masonic Order grew out of the Knights Templar, which was regarded by the Catholic Church as a heretical organization. In Philippine history, many of the revolutionaries who were sworn enemies of the Spanish friars were Masons. It was no big deal for me, however. My paternal uncle Rizal was a ring-bearing Mason. Though our DeMolay members plotted nothing more sinister than how best to politicize other unconcerned DeMolay members, I thought it significant that Masons, at least junior members, were once again involved in revolutionary activity.

At Hugh Wilson Hall too was my first encounter with an alleged government spy. Elmer told us that word had been sent to 3KP that Fely, one of the women who came regularly to our study, was a government agent. The sources were even explicit about her credentials: she was a member of the military’s Women’s Auxiliary Corps or WAC, with the rank of sergeant. I remember feeling more than a bit nervous while I listened to Elmer. Once again, I was reminded that what we were doing was not simple parish work. We were doing what we could to topple a regime and the regime was fighting back. Now we were under surveillance. The situation took on the character of a movie plot when a member pointed out that Fely had a crush on our chairman. Years later, after martial law had been declared, I imagined running into Fely in full-dress uniform, but I never saw her or heard of her again.

MY BIRTH INTO ACTIVISM was followed by a more precious one: the birth of my only child, Leon. I took Bernie to the Family Clinic in Sampaloc in the early hours of June 15, 1971. Her labor was prolonged and a quick X-ray showed that the baby was in an unusual position—a case of face presentation, the doctor said. When our baby was finally delivered by Caesarean section, his face was red, almost purple, the features mashed and contorted from the long ordeal. I thought it looked weird.

Bernie and I viewed the baby again a little later. The swelling of his face had subsided; he looked so peaceful and cute. I was relieved to see that we had a fine-looking boy. His quick recovery from a long and difficult birth was a triumph and a good omen.

NOTES

1 Almost 40 years later, I learned that Pope John Paul II had formulated similar ideas as a young priest. In Catholic Social Ethics, an unpublished book from 1952-53, he wrote: “In a well-organized society, orientated to the common good, class conflicts are solved peacefully through reforms. But states that base their order on individualistic liberalism are not such societies. So when an exploited class fails to receive in a peaceful way the share of the common good to which it has a right, it has to follow a different path.” The path could be revolution: “Class struggle should gain strength in proportion to the resistance it faces from economically privileged classes. ... The Church should view the cause of revolution with an awareness of the ethical evil in factors of the economic and social regime, and in the political system, which generates the need for a radical reaction. It can be accepted that the majority of people who took part in revolutions—even bloody ones—were acting on the basis of internal convictions, and thus in accordance with conscience.” (Quotes are from Jonathan Luxmore, “Unpublished Text Sparks Controversy about John Paul II’s Views on Economics,” Third World Resurgence, 2007, Issue No. 200.)

2 Some names are not given in full to protect the true identity of those concerned. In some instances, an alias is used because the chapter author never learned of, or wishes to protect, the person’s true identity.