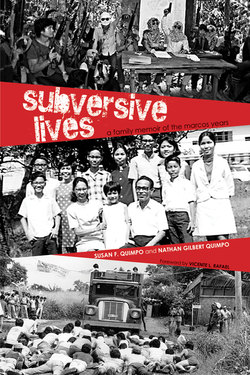

Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNothing Like Having Two Good Legs

6

DAVID RYAN F. QUIMPO

SOME MEMORIES OF my early childhood now appear like images in a dream: fragmented, incoherent, and blurred. Yet they remain. I see mentally ill patients dressed in dirty white muslin, walking aimlessly or lying on the pavement as my yaya (nanny) carries me over what appears to be a cement footbridge. In the next image, I am in an operating room, but this one, unlike others, has two operating tables. I am on one table. A nurse thinks I am fast asleep, but I can see what the doctors are doing at the adjacent table. Using a shiny stainless steel saw, a surgeon amputates a patient’s left leg.

In yet another image, I am seated on a bed. An attendant has just removed the cement cast on my feet with a rotating electric saw. Dr. Inocentes, my orthopedic surgeon, comes in and examines my foot. With his fingers, he firmly grips what looks like a button on my ankle. He mutters something about me being brave and then pulls the button. The button holds in place a string that goes through a hole in the bone, and passes through the other side—at my foot’s sole—to another button he has just severed.

It was only much later, in my early adolescent years, that I managed to piece together and comprehend these images. As a seven-month-old baby, I contracted poliomyelitis. My parents decided to move the family from Iloilo to Manila where the country’s only orthopedic hospital was located.

The National Orthopedic Hospital (NOH) was located inside the National Mental Hospital in Mandaluyong before it acquired its own premises on Banawe Street in Quezon City in 1963. My first three orthopedic operations were completed at the old site, while the next two were at the Banawe Street address. It must have been in Mandaluyong where I had the traumatic experience of witnessing an amputation. The scarcity of public funds at the time probably explains why the NOH had to maintain two operating tables in one surgical room.

As a result of polio, my body was paralyzed from my neck to my feet. Mom told me that for a time doctors were considering using the iron lung machine on me. The Emerson iron lung machine used in the mid-1900s helped polio victims whose breathing muscles were paralyzed. The patient’s whole body, from neck to feet, was placed in a large cylindrical steel drum where the action of breathing was mimicked by altering the pressure inside the drum. Luckily, it was not necessary for me to use the machine as I regained my capacity to breathe. Through a series of operations and years of therapy, my upper body recovered completely, even as large groups of muscles and nerves on my legs and feet remained dysfunctional. To stand up and walk, I needed metal braces on both legs as well as crutches on both arms.

Ryan, age five, holds a sheet of Easter Seal commemorative postage stamps for the year of the handicapped, to present to First Lady Leonila Garcia at Malacañang Palace (1959).

I was too young to remember these events or to know their significance. However, I do recall another image. I was on a beautiful, sunlit lawn with tiny butterflies flitting about. Mom ushered me through the garden and into a building. March 25, 1960, was a nice day when, at the age of five, I hobbled into the Music Room of Malacañang, the presidential palace, my arms and legs propped up with crutches and braces. To highlight the plight of an estimated 1.6-million handicapped persons in the Philippines, the government was issuing commemorative postage stamps called “Easter Seals.” I was chosen to present the first “Easter Seals” to the First Lady, Leonila Garcia, the wife of President Carlos P. Garcia.

One would think that the pain and hardship of multiple surgical operations, plus post-polio treatment, would have traumatized my childhood years. Surprisingly, it was not physical pain that affected me the most. Rather, it was the abnormal social life of a person with a marked disability that had a greater impact. When I was in the fifth grade, at age 11, I wrote a short speech for a conference of orthopedic specialists. I said:

Last year, I had my fourth operation and my schooling had to be stopped. My doctor says that next year, I shall have my fifth operation. I am getting pretty tired of operations. They are painful and I always cry. . . . In school, I find it hard to go up and down the stairs. While my classmates have fun at games, I sit around and watch from my desk. How I wish I were like them. . . . When I walk, some people stop and stare. Unkind children tease and make fun of me. I don’t mind too much now. My parents love me and I am happy. I am thankful that I’m alive. But there is nothing like having two good legs.

I was a boy with an inferiority complex, plagued with self-doubt. Will I get passing grades? Will I be truly accepted by my classmates? Will I ever date a girl?

My parents sacrificed a lot for their children. In my case, Dad and Mom took on the heavy burden of ensuring that I got the needed therapy, surgery, and care. Besides attending to my medical and material needs, Mom did her best to care for my emotional needs. When she saw me with friends or classmates, she would maintain a comfortable distance, knowing that I was trying to assert a degree of independence. When it was time to abandon shorts for long pants, she sewed special trousers for me. The fashion then was tight-fitting, but because I wore metal leg braces attached to special shoes, I had great difficulty putting on and removing my pants. My mother’s solution was to sew hidden zippers on the insides of both side lengths of the pants. Those pants succeeded in hiding my braces and gave me a semblance of being just like the other boys. However, there would always be one or two kids who discovered my secret and tortured me with their teasing. It was a relief when the fashion changed to bell-bottom pants.

I tried to overcome my feelings of inferiority by doing well in extracurricular activities and veering toward a barkada or peer group. I was not inspired by San Beda’s Catholic mission, and I did poorly in academics. However, San Beda’s extracurricular program offered what I considered the best practical education. I learned journalism through the student publications. And I learned organization and leadership by joining the Sodality, and later the Student Council. At age 12, I was single-handedly producing the newsletter for the Sodality and organizing religious retreats (which were actually “fun” nights) for kids younger than I. In grade seven, I was doing editorial and layout work on the Little Bedan, the official student publication. I also started organizing parties for my class.

When I was 12, a close family friend started to “borrow” me as company for their only son. Emiliana Jalbuena, whom we affectionately called Tita (Aunt) Emy, and her husband, Alberto, had four children. The first three were girls. The youngest, and their favorite, was a boy my age named Joma. Dr. Alberto Jalbuena, an ophthalmologist, had earned a fortune pioneering the use of contact lenses in the Philippines. His success and the inherited landholdings of his wife afforded the family the life of millionaires. They had a large, beautiful house in Urdaneta Village, an exclusive gated community in Makati. The family had a swimming pool, four cars, and uniformed servants and chauffeurs attending to their needs. At first, Mom was reluctant to allow me to spend much time at the Jalbuenas’. But seeing that Tita Emy treated me like a son, Mom accepted it as a temporary arrangement.

It was a dramatically different and pampered life for me at the Jalbuena residence. Waking up in the morning, I would slide open the glass doors of the air conditioned room and jump into the swimming pool. (I wore goggles that covered my nose and relied on my arms to carry my weight.) After a hot shower, I would find my school clothes neatly pressed and prepared on my bed. I would then eat a continental breakfast before the chauffeur drove Joma and me to school in a Mercedes Benz. I became seduced by the life of luxury, and my extended weekend stays at the Jalbuena residence became alternate week stays. Then they stretched to include summer and Christmas vacations. Ricky Yatco, Joma’s first cousin, joined us at the Jalbuena residence. Eventually, we formed a close-knit peer group. Later, my brother Jun, who was a year and a half younger than I, would join the barkada intermittently.

Ryan was eight and Jun was six in this picture (1962). Entering their teens, they were still close enough to be part of the same barkada.

Living with the rich sometimes gave me the feeling of being rich myself. Most of the time, however, it only underscored the real situation of my family. I felt this not only at the Jalbuena residence, but in school as well. When I was at Concepcion Aguila with my family, my allowance was 50 to 75 centavos a day. In school, some of my classmates had daily allowances of five to 10 pesos, and for a select few, it was double or triple that amount. At the Jalbuena home, Tita Emy gave me an allowance of 50 pesos1 a day.

I had just turned 14 when the barkada participated as poll watchers in the 1969 presidential elections where President Marcos was running for a second term. We were interested in meeting girls, and one of Ricky’s friends recruited us as poll watchers. So there we were at the poll precincts of the very rich in Forbes Park and Urdaneta Village, both in Makati, our attention riveted more to girls rather than to the ballot boxes. We enjoyed meeting girls, and while our participation in poll watching was totally insignificant, the exercise made me inquisitive about elections and the issues of the day.

EVEN BEFORE THE First Quarter Storm of 1970, my elder brother Jan was already into activism. A year older than I, he usually shared his experiences whenever we saw each other. He told me about the protest movement in his school and introduced me, through his stories, to Kabataang Makabayan. Although he didn’t elaborate on KM’s program, he impressed on me that the crisis in the Philippines called for radicalism, a revolution with ideals similar to the Katipunan of 1896. He was very serious, determined, and fearless when he spoke of his beliefs.

While Jan took on the serious path of revolution, my sisters Caren and Lillian were on the side of the “moderates.” They were in a group called SUCCOR which advocated reforms through a “nonpartisan Constitutional Convention.” The group was part of a movement led by the National Union of Students of the Philippines (NUSP) which placed its hopes on a new constitution that would avoid revolution and bloodshed as a path for change.

Reform or revolution? The question was answered for me by the First Quarter Storm. Most of my older siblings were in the January 26 demonstration. I was not. But hearing the blow-by-blow account on the radio, I could only empathize with the student protesters. A picture published in the newspapers reporting on the January 26 demonstration showed a dozen students trying to find refuge inside a jeepney. They were surrounded by riot police who were swinging their truncheons despite the obvious fact that the students were unarmed, helpless, and terrified. Young as I was, I came to understand the words fascism and state violence. I concluded that such brutes understood only the language of bullets.

Weeks later, as I left school to go home, I heard pillbox bombs exploding on Legarda Street behind San Beda College. It was another demonstration that was degenerating into a street battle. The smell of gunpowder was in the air. Something told me that the revolution was no longer a question of possibility, or whether or not it could be avoided. The pages of history were turning fast.

My feelings then solidified into a coherent cause as I read nationalist articles and books that mushroomed in campuses after the First Quarter Storm. Among the authors we read were Teodoro Agoncillo, Renato Constantino, Amado Hernandez, and Claro M. Recto. Movements outside the Philippines also inspired us, including the anti-Vietnam War movement, the student movement of the late 1960s in Paris and other parts of the world, and Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China.

But the most influential for me were Jose Maria Sison’s articles. I found his book Struggle for National Democracy, or SND, to be nationalistic, comprehensive, exuding confidence and certainty. In my eyes, no other book or document bore such clarity on the history, the current crisis, and the future of the Philippines. It convinced me that “national democracy” was the blueprint for a free, democratic, and prosperous nation.

I found it a bit exaggerated that Sison called reform-oriented groups and the Jesuits “clerico-fascists” in his article “Sophism of the Christian Social Movement.” However, his principal message was that the ruling elite in the country, led by Marcos and his cronies, would never share their wealth and power through peaceful means. Neither would they do it through “profit-sharing” or “constitutional reforms.”

WHILE SND AND other earlier articles by Sison did not explicitly advocate revolution modeled after China, his writings indirectly advocated the ideas of Mao Tse-tung. Sison espoused Mao’s writings as the most “advanced outlook” that could guide the revolution and avoid the problems in leadership.

Dr. Jalbuena had a collection of Mao books from what was then known as “Red China” which he bought when he visited there as a tourist. He bragged about his visit and was proud of his Mao collection because at that time it was rare for Filipinos to visit a communist state like China. One of the books he lent me was a little red book titled Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung.

One day I brought the little red book to school. I sat on one of the benches fronting the San Beda auditorium and began reading the first chapters. One of the passages that hit me was the famous Mao quote:

A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.

Gerundio “Bogs” Bonifacio, a classmate and close friend of my elder brother Nathan, passed by, greeted me, and asked what I was reading. When I showed him the book, he said, “A philosophy takes a lifetime.” Then he left, as abruptly as he arrived, leaving me to reflect on his words.

Mao’s little red book was translated into English and Pilipino. It was openly sold in a few bookstores in Manila and during various forums that catered to activists until martial law curtailed its circulation in 1972. KM first succeeded in recruiting low-income students from San Beda’s College of Law, then expanded to other departments and eventually to its high school. Believing in the cause of “national democracy,” I joined the KM chapter of San Beda High School in August 1970. I was 14 going on 15. There were just a handful of us in the KM chapter. One of our first projects was the publication of selected excerpts from Amado Guerrero’s (aka Jose Maria Sison), “The Philippine Crisis” in our high school paper, the Cub Recorder. Apparently, the issue reached the prosecutor’s office and the whole newspaper staff of about 20 students were summoned to a lecture at the Manila City Hall on the “dangers of communism.” We dismissed the lecture and warning as mere anticommunist propaganda that had no intellectual merit. But to avoid repression, we gave another name to our local KM chapter. We called it the Bedan National Democratic Movement.

Not long after joining KM, I got a firsthand taste of state violence when our peaceful picket along Mendiola Street opposing oil price hikes was dispersed by the military. An army jeep manned by three soldiers rode right into our human barricade, shooting live bullets from a machine gun. With my heavy steel braces on my polio-stricken legs, I was left alone on the road as my comrades took refuge inside the San Beda campus. One of the soldiers in the jeep aimed his pistol at me. He was about to shoot, perhaps thinking that the crumpled manifesto in my hand was a handmade pillbox. Fortunately for me, a pillbox from a military helicopter that was encircling the area targeting the protesting students, fell near the advancing jeep, missing the students and distracting the soldier who was about to shoot me. That gave me the opportunity to slip inside the school gates. “Akala ko yari ka na! (I thought you were a goner!),” said one of the school’s private guards who had been watching everything through the grilled gates.

Policemen beat demonstrators with truncheons during a rally in front of the Philippine Congress (January 1970). (Photo from the Lopez Memorial Museum Collection)

In the two years that followed, I continued to join protest actions. But in every demonstration or protest march, I tried to anticipate any violence by positioning myself in a “safe” area or making arrangements so I could leave early when danger was imminent. I didn’t know it at the time, but this pattern of anticipating danger and preparing for different possibilities would strongly influence my behavior for the rest of my life.

The Mendiola experience underscored what I was getting into—a revolution. And it certainly was not a “dinner party.” It dawned on me that someone with a disability like myself had perhaps little chance of surviving a revolution, much less a protracted one. Like countless others, however, I saw no other path to social change, and tried to muster the courage needed to face the challenges of the day.

In November of 1970, I attended the second national congress of KM in Abelardo Hall at the University of the Philippines campus in Diliman. As congress delegates registered their presence and obtained kits, I was informed that someone had taken my slot. It initially irritated me that a kasama could do such a thing, but upon discovering who it was, I laughed. It was Nathan, who had come with Jan! Until then, it was only Jan who was known to the family as a KM radical activist. This chance meeting of brothers was not only a reunion; it also gave us an opportunity to seal a pact of secrecy—to hide our political undertakings from Dad.

Our secret did not last long. My father was suspicious and was observing our movements, especially when big rallies were announced. “I know there is a scheduled rally,” he said as the first anniversary of the FQS approached. “If any of you goes to that rally, you’d better not set foot in this house again.”

Jan went to the anniversary rally without hesitation. Nathan went too. But I hesitated. I knew that my father meant what he said, and I pondered the consequences of my active involvement. Jan and Nathan had their tuition, dormitory fees, and part of their stipends covered by their respective scholarships. Nathan had a scholarship from the insurance firm Insular Life, while Jan was a Philippine Science High School scholar. I had no resources whatsoever. If I left home, Dad would most likely forbid me to even seek refuge at the Jalbuena residence. Where would I sleep? At 15, could I fend for myself? Could a handicapped person like me live like the activists I met at the KM national headquarters2?

I had no answers to these questions. So I stayed home and missed the rally.

NOTES

1 The peso-dollar rate in 1970 was 6.44 pesos to 1 dollar.

2 The national headquarters of the Kabataang Makabayan was then located at the penthouse of a building on Quezon Boulevard.