Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление538 Second Street

3

ELIZABETH Q. BULATAO, NORMAN F. QUIMPO, NATHAN GILBERT QUIMPO, LILLIAN F. QUIMPO, AND SUSAN F. QUIMPO

(Susan)

YEARS BEFORE WE moved into the cramped two-bedroom apartment on Concepción Aguila Street, our family life had every semblance of normalcy. The family lived in real homes—houses with vegetable patches in the backyard and room for children and dogs to run with abandon. I was born in 1961 when my parents and siblings lived on 538 Second Street. The “street” was one of the nondescript alleys in what was known as San Beda Subdivision. Nor was the area much of a “subdivision,” for it merely consisted of five dead-end, rather decrepit-looking streets that bordered San Beda College.

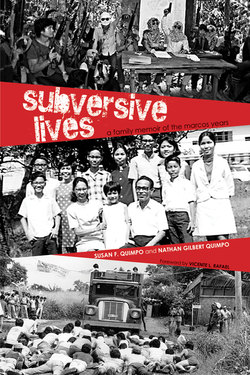

On the couch in the rented house on 538 Second Street are (from left) Nathan, Ryan, Jan and Jun, with Caren, Emilie, and Lillian behind. Seated on right are the sons of the house owner (1959).

538 Second Street was my first home, one that was in sharp contrast to the apartment on Concepción Aguila. And although the two addresses were only a short distance from each other, they came to represent completely different worlds for me.

(Norman)

MY FATHER, ISHMAEL (Maing) de los Reyes Quimpo, was the eldest son of Lolo Jose Quimpo and his first wife, Maria. Jose and Maria had fourteen children. When Maria died, Jose fathered another four with his second wife, Paz. Lolo Jose had been the provincial treasurer of Aklan before World War II. Aside from the local language Kinaray-a, he spoke Chinese, Spanish, English, and later also learned Japanese from a Japanese businessman whom he taught Chinese. Jose could have been considered a wealthy man because he owned property in Aklan and Capiz and tracts of land on the slopes of the mountain on the Aklan-Capiz boundary. He was also assigned to Tuguegarao as the provincial treasurer for Cagayan province, in northern Luzon.

My mother, Esperanza (Saning) Evangelista Ferrer, was her father’s favorite. Modesto Ferrer, whom we fondly called Laking, Pangasinense for grandfather, was the vice governor of Pangasinan during the time of President Elpidio Quirino. He was a member of the principalia and owned farms and mango orchards. Modesto lived in an old Spanish house in the town square of Mabini, a small town 11 kilometers from Alaminos. Laking was a traditional politician, a Liberal Party diehard. He used to declare that his tenants had to vote “straight Liberal” or else find some other fields to till. He had the habit of taking me along when he went to see his good friend, an incumbent congressman of Pangasinan, who lived in a palatial home somewhere in Quezon City. I used to accompany Laking to a small project house in Roxas district where the congressman kept his mistress.

Dad and Mom met as students in Manila. When World War II was declared, Dad went to Mabini, Pangasinan, Mom’s hometown, to say goodbye to her before joining his University of the Philippines ROTC unit which was preparing to move out of Manila. When he got back, his unit had already left for Bataan. Dad decided to return to Pangasinan. Thrice he tried to go to Manila so he could board a ship bound for his home province, Aklan. Twice the checkpoints set up by the Japanese military prevented him from proceeding farther. On his third try, he was apprehended by the Japanese as a possible spy (probably because he was an obvious stranger, not knowing how to speak the vernacular Pangasinense). In the nick of time, he was taken out of a file of prisoners destined for the firing squad. It was Laking who intervened and negotiated for his life. Dad then had to stay in Mabini. He and Mom were married soon after, and lived with Laking and Baing (grandmother) in Mabini until the war ended.

(Susan)

AT THE WAR’S END, Dad and Mom moved to Manila so Dad could complete his studies in engineering at the UP. Mom never finished her music degree at St. Scholastica’s College. By the early 1950s, they had moved to Iloilo City where Dad was hired as an engineer for the local Coca-Cola plant. With each move came new additions to the family. Elizabeth (Lys) was born in 1943, and Norman in 1945, in Laking’s old Spanish house in Mabini. Emilie was born in postwar Manila in 1948. Caren (1950), Lillian (1951), Nathan (1952), Ronald Jan (1954), and David Ryan (1955) were all born in Iloilo.

(Norman)

DAD EVENTUALLY BECAME chief engineer of the Iloilo Coca-Cola Plant. He had a good salary and a lucrative sideline repairing refrigerators on weekends. Life in Iloilo was pleasant although the family had to adopt a modest lifestyle due to the sheer number of mouths to feed.

My aunts said that the Quimpo family wealth was lost during the war in the panic to flee from the approaching Japanese.Lolo Jose died in 1949. Soon after, my father and his 17 siblings experienced poverty. In my father’s eyes, education was to be our deliverance. Dad and Mom vowed that their own children would have the best education possible. In Iloilo, this meant the Calvert School, the best elementary school where the province’s elite, mainly sugar barons, sent their children for their education.

(Lys)

GRADE SCHOOL AND high school were not particularly happy years for me. Growing up in Iloilo and going to the Calvert School with all the big shots, I was resentful of the fact that Mom and Dad had so many kids and couldn’t provide adequately for the family. As a grade school kid, I felt embarrassed going to the Calvert School riding a bus or a jeepney with Norman, Emilie, and Caren in tow and paying a two-for-one fare. I recall that on many occasions buses or jeepneys would bypass us because we were one too many kids. I would sometimes vent my humiliation by being very strict with my siblings, and even pinching Caren and Emilie if they so much as strayed from where we were waiting for a bus. Poverty and deprivation are harder to bear when you go to an elite school.

(Norman)

AT THE CALVERT School, I remember four of us Quimpo kids during recess, opening our common lunchbox containing mommy-made sandwiches and having to share those tiny bottles of Coke of the 1950s. (Since Dad worked for Coca-Cola, we were faithful Coke drinkers.) On the other hand, I had a classmate who showed me a 50-peso bill that was his allowance for the day, an amount that many workers counted as monthly pay back then.

(Susan)

UNTIL THEN, MY father had avoided taking his family to Manila where the cost of living was significantly higher than in the other provincial towns and cities the family had called home. But Manila eventually became a necessity. As an infant, my brother Ryan contracted polio and had to undergo five operations on his legs before the age of 10. The country’s only orthopedic hospital then was in Manila. That alone was enough reason to make the move.

In 1957, Lys and Norman were sent to live with Auntie Fe, my mother’s elder sister, and Laking and Baing in Roxas district in Quezon City. Lys started high school at Holy Ghost College (later renamed College of the Holy Spirit), a Catholic school for girls in the heart of Manila. Because of good grades in Calvert School, good entrance test scores, an obvious need for financial aid, and Mom’s earnest championing of her son, Norman was offered a scholarship at the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila Grade School and later a scholarship at the Ateneo High School.

The siblings, then nine, pose for a Christmas photo in Diliman, Quezon City (1960). The boys in front are, from left, Jun, Nathan, Ryan and Jan. Behind are Lillian, Caren, Lys, Emilie and Norman.

(Lys)

FOR SOME PART of my high school years and part of Norman’s grade school years, the two of us lived with Auntie Fe. It was the second time I lived with her. She looked after me when Mom and Dad returned to Manila after the war, until I was seven, and she thoroughly spoiled me. She would often take the trouble to curl my hair Shirley Temple-style. On several occasions, when I did not want to go to school, I had to be bribed with a promise of a new dress or new shoes or a new bag.

This time it was different. We sensed that we were really a burden to my aunt, who was doing Mom a big favor. We depended on Laking and Baing for tuition as well as for our daily baon (allowance), and Auntie Fe paid for our transportation to and from school. The family left us with them to continue our studies while they stayed for a few years in San Fernando, Pampanga, within two hours of Manila and the National Orthopedic Hospital, where Ryan’s treatment for polio had started.

(Norman)

DAD WAS A GIFTED person. His brothers marveled at his confidence in overhauling their father’s car when he was 14, without his father’s knowledge, at a time when cars were a novelty in the province. He reassembled the car without his father noticing any change in its performance. Dad had an ear for music, shared a love for the classical composers with Mom, and could tune a piano. He made wine, cured and cooked his own ham for Christmas, and prepared many a dish with Mom.

Dad steadily advanced from junior mechanical, to mechanical, to plant, to professional engineer by taking all the government regulatory exams. His affinity for machines was such that his company made him a member of teams that built the large San Miguel breweries in Polo (Bulacan province) and Mandaue (Cebu province) and Coca-Cola plants in various provinces.

When the decision was made to move to Manila to facilitate Ryan’s polio treatment and make it possible for all the children to go to better schools, Dad secured an assignment as plant engineer at the Coca-Cola Plant in San Fernando, Pampanga, a somewhat rural place like Jaro, Iloilo. But the move was not good for the family finances. He had started a business in Iloilo repairing refrigerators on weekends. His old-fashioned sense of craftsmanship endeared him to customers, so the business grew. He could have made his mark developing this repair service into a larger concern, but the move to Manila aborted this possibility. His partner, a mechanic with just a fraction of Dad’s experience and know-how, won a contract to service a large dealership of appliances just after our family left for Manila. The contract made Dad’s partner relatively wealthy.

(Lillian)

I REMEMBER A short stay in semirural Pampanga after Iloilo, during my preschool years. In our huge backyard, we would climb star apple (caimito) and guava trees. There were lots of banana trees, one big pomelo tree, and a very healthy kamias tree growing on an anthill. In a big, open laundry area by the backdoor, the maids would leave big tubs and barrels of water to soak up the morning sunshine and give us warm water for washing. Without a shower, we would use a tin can to pour water on ourselves, under the maids’ supervision.

The big, heavy, wooden kitchen door was barred at night. We had a maid who was quite determined to amputate the tails of all the cats in the neighborhood. She would hide behind the door and wait for the cats that raided the kitchen regularly. They would follow the smell of fresh fish, and she’d slam the door on their tails.

I remember the terrifying and exciting business of crossing the river that flowed between the house and the town proper. We had to use a wooden suspension bridge, holding on to a rope. It was a long walk to the bridge, but there was some compensation. In season, we would stop at a big aratiles tree and gather some fruit.

The major drama I recall was when Jan fell from a tall guava tree and into a big rubbish pit and broke his arm. Mom put his arm in a splint and hired a jeepney to take the two of them all the way to the National Orthopedic Hospital in Manila.

(Norman)

PAMPANGA WAS A way station to Manila, where my parents wanted to relocate and where Ryan was being treated for polio. Dad obtained another transfer, to work at San Miguel Beer Brewery near Malacañang and eventually other San Miguel plants—the Fleischmann’s Dry Yeast Plant, the Central Machine Shop, and the old Insular Ice Plant in Plaza Lawton. We rented a house near Auntie Fe’s in Roxas district. Ishmael Jr., nicknamed Jun, was born while we were there in 1957. My parents eventually tried to buy the house they were renting, as well as another unit in Project 8 in Quezon City, but both deals fell through. These failures weighed heavily on my parents, as if they had failed to give the family a proper home.

In Iloilo, the family lived on Lopez Jaena Street. In front (from left) are Norman, Emilie, Jan, Nathan and Caren. Behind are Lillian, Mom and Ryan (1956).

(Susan)

IN 1960, THE family moved to 538 Second Street in San Beda Subdivision, a short walk to the two schools my other siblings attended—San Beda College for the boys and Holy Ghost College for the girls. Like the Calvert School in Iloilo, our parents made sure these were schools known for discipline and academic excellence. And like the Calvert School, the tuition was beyond the family’s means.

538 Second Street was a two-story wooden house reminiscent of the airy houses built by the Americans during their colonization of the islands. The second floor was rented out to the Lee family, who were Chinese-Filipino; the first floor was our home. It had three bedrooms, each blessed with large windows with cast-iron grillwork. Its bathroom was dark and musty; a single bulb would cast enough light to occasionally expose a spider as huge as a man’s hand. The paint peeled, the floors were uneven, and the house itself seemed old and weary. Though it was unappealing, the house had one outstanding feature; it was surrounded by a yard, large by Manila’s standards. Trees stood sturdily every few meters, often laden with fruit—guava, cacao, mango and star apple.

The old house acquired the rural qualities of its new occupants. With the family came a host of pets befitting a farmhouse—ducks, dogs, a turkey, turtles, cats, parakeets, and the occasional hens and roosters. Clotheslines, thick wires suspended from erect metal T-posts, were installed along the width of the house. Close to the stone walls that surrounded the old house, we tended a vegetable patch with tomatoes, sweet potatoes, and the crawling, purple-veined alugbati, a popular vegetable on Panay Island. Behind the house, an outdoor kitchen evolved consisting of huge, thick aluminum pots propped up by construction bricks and firewood on the side, ready for camp-style cooking. Here, my mother and the laundry woman she hired would squat for hours either fanning the flames or doing the laundry, their skirts tucked between shin and thigh.

It was in this house where my mother expertly managed the household. Although my father’s salary was considered a sizable income, it was barely adequate to support a family of 12. It was my mother’s role to bear and rear children, and to provide my father her unconditional support. At the end of each work period, my father surrendered to her his brown pay envelope with his entire salary in it, as it was then the norm among married couples. As spouses and as parents, they had fixed functions—he was the breadwinner, she was everything else.

(Nathan)

OVER THE YEARS, prices of goods and tuition rose steeply, and Dad and Mom could hardly make ends meet. Mom often wracked her brains thinking of ways and means to save or earn a little money, and to put food on the dinner table. Somehow we never missed a meal. Well, not exactly. I usually brought tuna or cheese pimiento sandwiches to school but the bread was so inferior and light that I often felt hungry again after an hour or two.

When the family was really hard up, we were down to eating rice and eggs, day in and day out. The rice was bought at the market, but the eggs were a different story. Our Aunt Toyang, my father’s sister, had a modest poultry farm and she sold eggs to Mom at a very low price. There was very little money for buying eggs, but Mom was too proud to ask if she could have them for free. Instead, she asked to buy the abnormal eggs and the rejects—eggs with cracked shells, eggs without shells, extra-large eggs, extra-small eggs, eggs with reddish spots. Aunt Toyang just gave them to her, insisting that these were of no commercial value anyway. Sometimes an old White Leghorn chicken came with the eggs.

Susan, the youngest, is with Lys, the eldest, at 538 Second Street in Manila, where Susan was born (1962).

One day Mom brought home from the poultry farm some gaily-designed muslin sacks used for B-Meg chicken feed. After washing the sacks thoroughly, she cut and sewed shirts, dresses, shorts, and pajamas for us, and sold the rest of the sackcloth to neighbors. Soon, sackcloth, best used for rags, became an important source of extra income for the family and our daily wear.

(Lys)

I WAS EMBARRASSED to take my friends to our house on Second Street because the living and dining rooms were so shabby—our furniture had torn upholstery that we tried covering with sackcloth, and Dad’s work table that overflowed with greasy tools and sooty machine parts was right next to the dining table. This would have been all right if you didn’t compare your house to the houses of your friends. And imagine coming from an elite school like Holy Ghost College and then wearing dresses made from B-Meg feed sackcloth! Of course I came to know better as I grew older, but the norms and the social milieu of the early 1960s were different.

(Norman)

DAD WAS A strict disciplinarian. I gathered from him and his siblings that this was, among other reasons, the result of their father’s having been a gentleman raised in the tradition of the Spanish colonial families. For Lolo Jose, the whip was the standard disciplinary tool. But being part of the tradition was only half of the story. My father and his siblings were raised in a mix of Spanish religiosity and American Bible faith. The version that reached us, the children of Ishmael, had a decidedly American flavor. Our preteen years were nurtured by the stories from a set of books called The Children’s Hour, published by an American Protestant sect. The books, a collection of Bible stories and stories set in contemporary American neighborhoods and inspired by Christian themes, always had a moral lesson to bring across.

I remember only two stories from those books. One was about a boy who liked to play with firecrackers. He was warned by his mother time and time again to be careful, but he was too stubborn. Bored with just lighting the firecrackers in open spaces, he experimented with the effects of the devices on various objects. He paid for his disobedience when a firecracker he lighted in a flowerpot sent shards of pottery flying, blinding him in one eye. The other story was of Jesus’s last meeting with his disciples. He promised them, “I shall be with you all days, even to the end of time.” That I remember these two stories in particular might be symbolic of how we, the Quimpo kids, grew up—between a sense of discipline and obedience, and an expectation of the coming of God’s kingdom.

(Susan)

MY FATHER POSSESSED such an air of authority that I always thought he was a very “large” man with a gruff voice. Actually, he was a mere five feet, four inches and probably weighed less than 120 pounds. One of my life’s earliest lessons was: “Do not do anything to anger your father.” Even at the age of three or four, I was aware of this. In fact, all of us siblings tried very hard to stay away from him. In our household, rules were rules; if you broke them, you’d get severely punished. The boys, in particular, had to learn this the hard way.

Ryan and Jun were the best of friends and the worst of enemies. When they fought, I knew it was best to stay away, lest I get hurt. When they were around nine and seven, they got into a fight, the reason for which I no longer remember. What I remember distinctly, though, was that they did not expect Dad to come home early from work that day. Adequately briefed by Mom on the boys’ latest misdemeanor, Dad whipped out his leather belt and stormed through the house shouting for them. The boys expertly sneaked outdoors and in a flash, Jun climbed up the huge mango tree, discreetly hiding in its thick foliage. Ryan sought to do the same, but with his polio-stricken legs, he could only use his arms to climb the first boughs of our little guava tree that was barely seven feet tall! I can still remember Ryan’s spindly legs sticking out of the clump of guava leaves while I cringed, expecting the worst. Dad, of course, spotted Ryan in no time and yelled for Jun to come out as well. Soon they were both behind closed doors; the thud of the leather belt on their buttocks alternated with incessant crying.

Everything had to be in place. There was no room for excess. Every centavo was accounted for long before my father surrendered his pay envelope. And for my parents, there was no room for leisure. Through it all, Mom held the delicate balance—my father’s stubborn pride, the many children to feed and clothe, the exorbitant tuition, and Ryan’s medical needs. Despite the challenges, Mom made the house at 538 Second Street a home.

It was the home where Lillian had the habit of adopting stray kittens. She nursed them in a shoebox and fed them milk dispensed from an eyedropper. It was also where Lys groomed Duke, a handsome German Shepherd, a gift from a kind monk from San Beda College. Lys would send the dog after street urchins who scaled our fence and wrought-iron gate, coveting the ripe fruit in the trees in the yard. The fruit trees were always a cause for contention. My siblings would spend hours peering at the tree branches in search of a new clump of mangoes or the ripest guavas. They yelled “reserved” or “save” to claim that which was yet beyond reach. Then, when the fruits ripened, they would entice the fruit to fall with sticks and stones, and thereafter resume their fight for ownership.

It was at 538 Second Street where my mother taught her girls to sew—mending rips and holes on my father’s shirt collars and sock heels. She showed me how to stretch the ripped sections over bended knee, and weave the frayed edges into submission with needle and thread.

It was home to our many pets—the turkey and occasional chickens we would fatten before my mother would slit their throats and dip them in hot water to loosen their feathers. It was in this house where our pet turtle disappeared during a typhoon. When the flood waters subsided, we cried, having found the turtle box empty. But Mom assured us that the turtle was fine and living close by, happily enjoying its newfound freedom.

The Lee family, who lived above us, were the best of neighbors. They had a TV set, a car, bikes, skates, and most importantly, a generous nature. Whatever toys our parents could not provide us, the Lees shared with us. The Lee children were the same ages as some of my siblings, and ties were quickly cemented. One of the highlights of living on Second Street was the wedding of one of the Lee daughters. The entire neighborhood gawked in disbelief when the groom’s parents brought TV sets, a refrigerator, and a complete set of bedroom and living room furniture as dowry. We thought the Lees were the richest people on earth.

At home in Second Street are Ryan (left) and Jan (rear), with Lys and Susan (1964).

It was soon after that wedding that the Lees announced they were moving. After they left, the second floor of the house remained unoccupied. Our landlord refused to lease it to someone else. In fact, he regretfully told my mother that we also had to leave. It was too costly to try to maintain the old house, he said, and he was trying to sell it. He generously allowed us to stay while my mother searched for another abode.

IT TURNED OUT to be a long search since my parents could not afford to pay higher rent. We could not move farther from my siblings’ schools—without a car, it would be difficult to take Ryan to San Beda. The best Mom could find was a cramped two-bedroom apartment on a neighboring street called Concepción Aguila.

The old wooden house on 538 Second Street was demolished soon after we left. The new owner ordered the fruit trees felled, and the wrought-iron gate and fence were replaced by a high cement wall. Then a small building was erected, maximizing the space within the walls, leaving no room for a yard or a vegetable patch. We heard that the new owner earned a lot of money renting out rooms to students who attended San Beda and Holy Ghost College. I would often walk by Second Street, reminiscing about the fruit trees and the big yard and wondering how the turtle we lost in the big flood was faring.