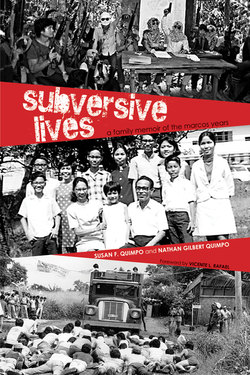

Читать книгу Subversive Lives - Susan F. Quimpo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеForeword

Distinguished historian Vicente Rafael, whose encouragement and support were instrumental in the preparation of this memoir, received an early copy and was invited to provide his reflections. His response was the following essay on the book as well as on communism and its role in shaping Philippine history, one of his current interests as a historian. Some of the authors played important roles in the Communist Party of the Philippines or the National Democratic Front during the period covered by the memoir. Although this book was not intended to be about communists and communism, it does touch on these subjects from a personal perspective, focusing on the collective experiences of the siblings, several of whom found themselves attracted to the same political solution to the Philippine crisis that was laid bare during the Marcos regime. —The Authors

Radiant Hope, Dark Despair

THERE ARE NO monuments to communism in the Philippines. Instead, there are numerous statues of nationalist figures. Whereas it is common, perhaps even essential, to commemorate national heroes, the nation seems unable and unwilling to acknowledge those whose nationalism was colored by communism. Even the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, which is run by a private foundation and not by the government, commemorates the victims of the Marcos regime primarily as nationalist martyrs rather than members of a radical revolutionary movement. Why this absence of memorials to communists?

Since the beginning of the 20th century, communism of some sort has been around in the Philippines. In 1901, Isabelo de los Reyes returned from Barcelona where he had been imprisoned, loaded with Marxist and anarchist literature. Along with other ilustrado nationalists like Lope K. Santos and Dominador Gomez, he led the formation of militant labor unions during the first two decades of U.S. colonial rule. In 1930, some 34 years after the start of the Philippine Revolution and 13 years after the Russian Revolution, the first Communist Party of the Philippine Islands (CPPI) was founded. It later changed its name to the Communist Party of the Philippines (after its merger with the Socialist Party in 1938) and became more commonly referred to by its Tagalog name, Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas (PKP). It was first led by a printer, Crisanto Evangelista. Flourishing in the Commonwealth era in the midst of the Great Depression, the prewar PKP was nurtured by the Communist Party of the U.S.A. and was linked to the Third International, or Comintern, based in Moscow.

In 1968, on the 55th birthday of Mao Zedong, in the same year as the Prague spring, the general strike in Paris, the student uprisings in New York, and the Cultural Revolution in China, a new communist party emerged, often referred to by its English name, the Communist Party of the Philippines. Where the old PKP was founded in one of the oldest sections of Manila, the new CPP was established in a remote rural area of Northern Luzon. Influenced by Maoism, which the new Party regarded as the culmination of Marxist-Leninist thought, it was and continues to be led by former PKP member and UP English instructor Jose Maria Sison, who has lived in exile in Utrecht since 1988.

Without doubt, both the old and new communist parties have played important roles in the political and cultural history of the Philippines. The PKP was active in shaping labor and peasant unions though never quite able to control them. It sought to radicalize the issue of independence by linking national sovereignty to anti-imperialism and forged international affiliations with the communist parties of the U.S., Indonesia, Japan, and China, sending party members to attend meetings and universities in Moscow and demonstrating on behalf of Republican Spain. Following a Comintern directive, it formed a Popular Front aimed at containing the spread of Japanese fascism, though it failed to unite the front’s different elements. It lagged behind the peasant-led Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan (HMB) in resisting the Japanese during the war but fielded candidates, as part of a left-wing alliance, for local and national offices in the postwar period. The PKP’s leadership under the Lava brothers at first denounced, then promoted, then gave up on the HMB or Huk Rebellion just as it initially resisted then capitulated to Marcos and martial law.

The new CPP began small, breaking away from the old PKP over ideological and strategic differences that reflected the global rift between the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union. But in the 1970s, it was quickly growing to be the most organized and militant alternative to the repressive Marcos regime. It benefited from the intellectual and organizational skills of committed cadres recruited from the university-educated, multilingual middle classes. By the early 1980s, the CPP and its military wing, the New People’s Army (NPA), had succeeded in controlling significant parts of the country while forging an international solidarity movement, under its legal face, the National Democratic Front (NDF), that included overseas Filipinos, Filipino-Americans, U.S. congressmen and Western Europeans to put pressure on Marcos.

In time, it was plagued with internal debates brought about by its growth, leading to ideological rifts, horrific purges, bitter recriminations and strategic blunders, culminating in the party’s marginalization from the EDSA uprising that led to the ouster of the Marcoses in 1986. Fierce efforts at reform and rectification followed, along with internal dissent and expulsions, and attempted and actual assassinations of former cadres deemed counterrevolutionary. Its armed insurgency waned, then experienced a resurgence by the late 1990s, punctuated by on-again, off-again negotiations with the Philippine government along with open participation in national elections. Combining ideological rigidity with political opportunism, the CPP has been surprisingly resilient, surviving internal turmoil, repeated splits, state violence and international marginalization.

Communism has thus been part of Philippine modernity for over a century. It has supplied nationalism with its anti-imperialist outlook, mass movements with much of their organizational structure, aesthetic vocabulary and political strategies, and even civil society with the ideological ballast of “national democracy.” But unable to seize state power, communism has also been relegated to the margins of Filipino historical consciousness. It is as if it exists and doesn’t exist at the same time, much like the spectral presence invoked in the Communist Manifesto.

This is perhaps why there are no monuments to communism. Monuments act as tombs that bury and so keep in place the ghosts of the past. They allow those in the present to commemorate the dead and thereby overcome their absence. The fact that there are no monuments to communism as such means that there is something about it that defies commemoration and mourning. Though it has figured prominently in anticolonial struggles, its history remains unassimilated into the dominant narrative of how these struggles have culminated in national sovereignty. For this reason, communism seems peripheral to nationalist consciousness and so defines its limits. It haunts the nation in ways that cannot be fully accounted for, much less entombed by the historical narrative of nationalism. As nationalism’s uncanny other, it is bound to return in ways both unexpected and unsettling.

Symptomatic of communism’s recurring visitations is the recent spate of memoirs and biographies of those who were part of the revolutionary movement and the party, both old and new. Most of these tend (and largely fail) to be hagiographic: books on (and at least one by) the Lava brothers, or on Jose Maria Sison, or on martyred activists such as Edgar Jopson, Lean Alejandro, Lorena Barros and Emmanuel Lacaba. A few merge personal reflections with wide ranging policy critiques of the party, such as the books of Joel Rocamora and Bobby Garcia, whereas others offer intense personal reminiscences of youthful involvement in the movement, as in the essays in Militant but Groovy on the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK).

Subversive Lives encompasses these tendencies but adds something more. Written as a family history, it also furnishes us with powerful testimonies on the era of Ferdinand Marcos and Jose Maria Sison, along with narrative on the vicissitudes of the revolutionary movement. Each Quimpo sibling (even those who had nothing to do with the movement) bears witness to the events they and others did so much to shape. From aborted attempts to smuggle weapons for the NPA, to heady times organizing “spontaneous uprisings” and general strikes in Mindanao, from the cruel discovery of the cause of one brother’s death at the hands of a kasama (comrade), to the near hallucinatory tales of imprisonment and torture at the hands of the military, these stories remind us of the personal costs and the daily heroism of those who joined the movement. But they also bring forth its messy and unresolved legacies: of sons alienated from their father; daughters abused and victimized by the military and deluded by a religious cult; brothers lost to the war; friends betrayed, comrades purged, and revolutionary affection soured and then destroyed by intractable ideological differences. Such stories are much less about an unfinished revolution as they are about an inconclusive one.

To read these accounts, each so rich and distinctive in its tone, is to hear the rhythm of the revolution. There is the blast of pillboxes so omnipresent in the early days of student activism, bursting on streets and hollowing out heads; the sound of fists pounding faces and body parts shocked with electrical wires to the hiss of the interrogators’ demands for more information that one either did not have or did not want to give up; the chants of demonstrators as masses of bodies fill up streets, waving banners, defying cops, escaping tear gas; the quiet routines and rituals of prison life; the songs of solidarity and poems of militant resolve; the sigh of a guerrilla husband writing from a red zone in Bicol lamenting the absence of his wife forced to live underground in the city.

As with the great majority of memoirs about the revolution, Subversive Lives is written in English, indicating the university-educated, middle class nature both of its authors and its presumed readership. This is not surprising given the fact that communism has historically drawn to its ranks the more progressive elements of the nationalist bourgeoisie, especially their daughters and sons. Poised between the conservative remains of a prewar colonial order and the emergent possibilities of a postcolonial society, Filipino youth were particularly responsive to militant calls for change. As with the youth of other countries in the 1960s, they saw themselves occupying a liminal position, at once agents of and traitors to their parents’ class interests. They thus came to embody the familial tensions characteristic of the revolution. They searched for new sources of authority and alternative bases for legitimacy. Drawn out of their homes and schools into the streets, factories and countryside, they came to assume novel identities that left them unrecognizable to their parents and teachers. They defied existing laws in order to create new ones while setting aside existing family ties to go underground and there forge new kinship bonds.

Indeed, this book shows how the revolution radically reshaped the fundamental features of middle class family life. The wall between the personal and the political, so characteristic of bourgeois culture, is completely, sometimes disastrously, demolished. Romance flowers while attending discussion groups and rallies. It intensifies amid the violence of fighting in the field, and is then cut short by news of the other’s death, or endangered by the strategic needs of the Party. (In the case of Emilie Quimpo, who joins not the Communist Party but something equally totalitarian, the Opus Dei, the effects of a disrupted life requiring displacement and disconnection from friends and family are functionally similar.)

Indeed, any semblance of domestic life proves impossible given the imperative to live underground. The revolutionary movement becomes exactly that: a life defined not by stability and routine but by constant movement from one safehouse to another, or from one prison to another. Itineraries become indefinite, arrivals deferred, meetings subject to detour and the constant possibility of ambush. Subversion entails leading a subterranean life, whether in Manila, Cebu, Davao, Paris or Utrecht. In this context, all identities melt into air, becoming flexible and disposable. Joining the insurgency means adopting new names and masking one’s own. Escaping the forces of the state requires constant disguise and deception. Forced into exile, one is constrained to ask for political asylum and take on a new citizenship, becoming foreign to one’s self even as one waits to return to a country and a family that will never be the same. Most painful of all, as in the cases of Jun and Jan Quimpo, one can die mysteriously or disappear altogether, giving up one’s identity and any hope of being identified, leaving behind a barely identifiable corpse, or worse, no body at all, and therefore, no legacy.

A mother is inexplicably killed in an accident, traumatizing the daughter who witnessed the scene, and a father dies deeply saddened by and unreconciled to the political paths taken by his sons. And the sons, seeking to overcome the world of their father, find themselves contesting the wishes of the Father of the party himself who comes to identify the fate of the revolution with the reaffirmation of what he takes to be an absolute, inflexible political line. Such a double defiance is bound to exact a high price, including alienation from the family and excommunication from the party.

Life in the revolution as revealed in this book consists of many things and many acts: mobilization, protest, debate, struggle, captivity, torture, killing, escape, exile, and so forth. It is not, however, a life of remembering and mourning. This is perhaps what sets communism, as it is driven by revolution, apart from nationalism. The nation, as Benedict Anderson has taught us, is an “imagined community.” Imagination is built on the inclusion of others within a bounded territory, including the dead, who are commemorated by the living as part of the same national “family.” By contrast, communism is not wedded to one place but from the start seeks to root itself like its enemy, capitalism, in every place. It is thus inherently cosmopolitan, bearing an internationalist vocation that urges the transcendence of national identities and the crossing of national boundaries for the sake of creating transnational proletarian solidarities.

Nationalism in contrast tends to suppress class conflict in favor of cross-class alliances. Where communism sees the working class as the main agents of historical transformation, nationalism, despite its republican rhetoric, invariably sets the bourgeoisie as the natural leaders of the people (see the Malolos and all postwar Republics). Nationalism, especially in a colonial context, seeks sovereignty from a foreign power within a delimited territory, a market economy directed by the national bourgeoisie, and a stable class hierarchy led by elites acting as representatives of the people (see Rizal, Quezon, Recto, Marcos, Aquino, . . . Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo). Unlike nationalism, communism confronts capitalism in its global form of imperialism, in the hope of establishing a classless society that would lead to the withering away of the state. It has no time to mourn because that would require restoring the class and national particularity of the living who remember the dead. It would, in other words, mean allowing nationalist sentiments to rule over communist revolutionary resolve. “Workers of the world” would have to yield to “workers of the Philippines,” the “Internationale” to “Lupang Hinirang” rather than the other way around.

Compared to nationalism, there is thus something wildly impossible and highly improbable about “communism.” It is worth noting the origins of that word in the Latin communis, to come or be bound together, to hold something in common, which we can gloss as: to be by being with others. It was commonly used to refer to the pre-Marxist revolutionary movements and secret societies in France in the 1830s. Marx himself was notoriously elusive in his attempts to define what might constitute a communist society (see especially The German Ideology). For Marx, communism was not simply a political movement but also the social conditions that such a movement would ideally yield. In such a society, human association would be predicated on overcoming the very source of alienation: the necessity to labor itself. Surpassing both capitalism and socialism, a communist society would be one where freedom and justice were perfectly aligned, thanks to the abolition of all forms of human and natural exploitation. It would put an end to the division of labor and the invidiousness and inequalities such a division implied. As a radically egalitarian society, communism, should it ever exist, would foster unconditional hospitality and friendship for one another. It is not for nothing that communists refer to each other wishfully and without irony as kasama or comrade.

Nationalism has periodically sought to appropriate communism’s utopian vision only to turn away from its more radical demands. It is as if there is something about communism—its appeal for revolution as a way of life, for the destruction of private property, for the abolition of the state, and for the radical leveling of class, gender, ethnic and racial inequalities—that proves impossible, if not profoundly threatening to the constitution of the nation-state. The means for achieving communist sociality—revolution—is historically what links nationalism and communism in the Philippines. But it is also what separates the two.

As the Quimpos tell it, revolution requires a kind of dedication that calls for sacrificing everything to a single cause. It tends to subordinate all other forms of human relationships to a particular “Line of March,” reducing the world into stark categories of friends or enemies (as “revisionists,” “puppets,” “counter-revolutionaries,” and so forth). In the name of liberation, revolution ironically creates new forms of oppression as it seeks to transform everything into an instrument for the realization of its goal. While nationalism seeks to dominate revolutionary power, communism is inextricably bound to it. For nationalism, revolution is a means to an end and therefore a transitory condition. For communism, revolution is a permanent possibility, the exception that is also the norm. In revolution, nationalism and communism come together only to split apart, forming alliances founded on mutual suspicion, crass calculation, and potential enmity.

Memoirs such as Subversive Lives implicitly apprehend this fact without, however, fully comprehending it. Reading the lives of the Quimpos, one senses the deconstructive power of revolution at work, unhinging much of what we, during these unrevolutionary times, take for granted, such as the categories of national identity, private property, social hierarchy and political order. It is a power that the PKP-HMB and the CPP-NPA-NDF also sensed and sought to wield. But like the Philippine state, they too have always failed to tame its uncanny force, much less render a “correct” interpretation of its meanings and demands.

This is perhaps why communism with a small “c” cannot be monumentalized because, like revolution, it cannot really be buried. Every time it is declared dead and laid to rest, its specter returns to confront the vampire-like (as Marx described it) workings of global capitalism and the awful catastrophes these spawn. It still haunts contemporary articulations of Filipino nationalism in the latter’s attempts to counter the alienating effects of globalization, especially in its most pervasive form: the overseas contract worker.

Proof of this spectral presence are memoirs such as Subversive Lives that bring forth something of the revolution when it was still revolutionary, that is, still a movement, and thus still the living possibility of enacting the exorbitant promise of communism. It is, of course, a promise that is also a threat, bringing in its wake the prospects and perils of resistance and comradeship, the radiant hope and dark despair of a future yet to come. This much we have come to learn from our recent history, both national and global. The great value of this book lies less in conveying the lessons of this past as in enacting its unrealized possibilities and embodying its unsettling afterlife.

Vicente L. Rafael

Professor of History

University of Washington

Seattle, Washington