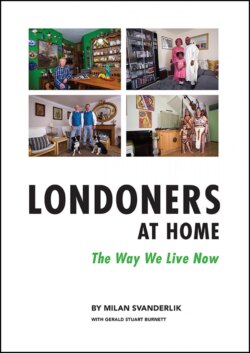

Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? LIVING IN A GARAGE

ОглавлениеDennis Albert Reynolds

In this great city of ours, a city of almost unimaginable wealth and the capital of a country that brags endlessly about being the fifth richest nation in the world, some Londoners struggle to find anywhere decent to live, with many reduced to sleeping in cars, in paladin bins, in garden sheds and, indeed, in garages. Dennis was one of those Londoners, for his home was a lock-up garage in Brixton. However, Dennis’s predicament is not wholly an economic one; it is also a manifestation of his powerful desire to lead an ascetic life. A deeply religious man, he has abandoned most of his possessions, and with material things no longer having significance for him, his mission to purify his life has led him to act in ways that may puzzle some and antagonise others.

Photograph: Dennis Albert Reynolds in front of his windowless garage - his home in Brixton. (Photography: 29th April 2017)

The full story:

One Sunday morning, I found myself chatting to an impeccably-dressed, young sales agent, close to the smart reception desk of one of the many new glass and steel tower blocks that now reach high into the sky along the banks of the Thames. The building was still under construction but most of the flats were already sold. I was conducted to see a two-bedroom apartment with only a side view of the river (all the premier, river-facing flats had already sold) although this unforgivable shortcoming was reflected in the more modest price - under five million pounds. The show flat was lavishly furnished and the careful attention to every detail was truly impressive, but the view was indeed somewhat impaired by the less than elegant facades of the adjacent office blocks.

“I fully understand your concerns about what is not such a perfect view,” said the charming agent, very politely. “The flats on the front elevation, with the full river view, were sold by our overseas offices within minutes of being released. However, we do still have one remaining, four-bedroom apartment on the 40th floor, and that has an unobstructed, panoramic view of the river and the City. That one will sell for around £36 million but it is, of course, rather more than a flat, more than just somewhere to live; it should be seen primarily as an investment.” The charming agent smiled an impeccably fabricated smile, the sort of ever-so-slightly menacing smile of someone who knows that she has completely wasted her time.

Three days later, I emerged from an Underground Station in south London to be met by someone equally well turned out, though not this time a sales agent; this was Dennis Albert Reynolds who had kindly agreed to let me photograph him at his home. He is a well-built, muscular man, someone who must turn heads even in his forties. He leads the way and soon we enter a secluded courtyard. He unlocks, then pulls up the metal shutters, opens a door and invites me in to see his home - it is a garage. He apologises and explains: “Well, this was my home until this afternoon. I was three days late with my rent, it’s £100 a week, and my landlady made such a big fuss about it, so now I’m out of here. I’ve had enough.” There were no windows and no running water either; the temporary cable that brought electricity into the otherwise dark interior was now disconnected.

Of course, in the circumstances, Dennis was a man of few possessions; he is a barber and the few tools of his trade all fit into a small holdall. Dennis folded his canvas bed, supported by a few metal rods, and took it outside, ready for his final departure. I then photographed him in front of what, until that afternoon, had been his home. Standing there, peering into this gloomy lock-up, I could not get out of my mind the opulent interiors and panoramic views I had been gazing at the Sunday before, the glass palace in the sky that overlooked the Thames; it is that image that contrasted so starkly with the picture that was now before me, a serenely smiling young man who had just lost the only place he had to sleep in. Bizarrely, he seemed more disturbed by my concern for him, which I had clearly failed to conceal, than with his own sorry predicament.

My original intention was to document the fact that, in this great city of ours, a city of immense wealth and the capital of a country that brags endlessly about being the fifth richest nation in the world, some people are obliged to live in garages. I had myself never met anyone in such a predicament but then again, most of us haven’t. However, one does hear about such cases and if one is to believe reports in the serious press, this is neither a new nor rare phenomenon. Of course, there have always been people who converted their oversized or unused garages into playrooms, or studios, or even granny flats and local authorities have often had to intervene where planning restrictions have been flouted, but now, with the cost of housing in London so high and the availability of cheap accommodation so limited, some Londoners are forced to live in places without any amenities at all, places that are worse than the shanty towns of Latin America or the Far East. But Dennis’s predicament is not wholly an economic one; I soon discovered that it is also a manifestation of his powerful desire to lead an ascetic life.

Fascinated, I asked Dennis to tell me something about himself; this he did with extraordinary ease, radiating warmth: “I was born in Lambeth, so I’m very much a local boy. Both of my parents came from Jamaica and by the time they arrived to the UK, they already had three children - in the end, they had nine of us altogether. My brother Derrick and I were identical twins and we arrived towards the end of this line of children.”

“I started in a local infants school but when I was six, my mother decided to take five of us back to Jamaica, back to what was her home country - it didn’t feel like that to us, of course, as my brother and I only knew life as Londoners. Having said this, I have to admit that I also felt we had, in some way, returned to our own community. I’d only experienced life as a metropolitan boy, so living so close to the lush nature of a tropical island felt really exhilarating. It also struck me that the people there seemed somehow more alert. Nevertheless, after living there for two years in what were pretty modest circumstances, I came to miss what now felt like luxuries - having a bath with running water and a flush toilet; these were perhaps small things but they were things I remembered, things we took for granted in London, which I saw as my real home. After two years, we came back to London but those memories of Jamaica will stay with me for ever. Perhaps that is my true spiritual home,” Dennis adds with a wistful smile.

Though Dennis’s father was a carpenter by trade, he freelanced as a barber and he was in great demand. His mother was the homemaker but she was a dressmaker too: “She had to be,” Dennis chuckles, “with nine children to kit out, she didn’t really have much choice.” He went on: “I went to the local comprehensive school where it was certainly something of an advantage to have several older brothers, who were big, strong lads and all prominent in the community. Both my twin brother and I were very creative and artistic; we were never anywhere without a pencil, sketching, or we would be building something, creating things out of nothing. This creative flare encouraged me to enrol at South Thames College, though that was the first time I became aware of explicit, raw racism. My own teachers struck me as intellectual racists and it was soon clear to me that I was probably wasting my time, hoping to get a job in the arts, simply because of the colour of my skin. At one point, I actually contemplated studying architecture but in those days, you never saw a single black face in any of the famous firms.”

“I was 18, my best years perhaps, and I loved the attention I used to get. I was always striving to look smart, to be ‘with-it’, so I went for ‘Option B’; I started to earn my own money and life was good. This isn’t to say that before then, us two brothers were idle; we’d both followed in father’s footsteps, both of us were cutting hair, and both of us were pretty good at it - I already had repeat customers when I was only twelve. To be honest, at that time, I wasn’t really aware of the famous, West End hairdressers, like Vidal Sassoon, but in any case, we were black, so making it big in the smart, mostly white parts of London, as a black barber from Brixton, would have been pretty improbable.”

In fact, Dennis became a very successful barber, and not just any ordinary barber. Having originally worked for his elder brother, Dennis broke free and, using the proceeds of the sale of his flat, he opened his own establishment, trained an Eritrean called Merron, and employed his twin brother, Derrick. I was told that his salon became the place to go to in Brixton, the place where everyone in the know went to have their hair cut - since the 1990s, when it opened, it was always busy. The twin brothers’ artistic flair also came into its own, and the salon itself was the most stylish place in the whole area.

Alas, all this success had its dark side too: Dennis continued: “We were full; we were always full; we could have stayed open day and night, never closing.” For the first time, Dennis’s expression changed and he suddenly became much more serious: “Milan, I felt that I had become a slave to it all. Everyone clamoured for my personal attention; I no longer had any social life at all; with all of this going on around me, I felt that my life had no space left in it for ME.”

“Mind you, it was not just hard work: when I was 27 and I’d got the shop, I felt an intense desire to have children and I got together with the sweetheart of my teenage years. We had two daughters; they’re now teenagers, of 15 and 18. They live with their mother as we don’t live together as a family any more. We parted company primarily because my spirituality and faith had started to be a more prominent part of my life and because we disagreed about the moral codes that should guide us as a family.”

Dennis’s father was not a religious man but his mother undoubtedly was; she was very much a part of the local Seventh Day Adventist congregation. Dennis was religious too but it was a supernatural experience at Whitechapel, when he was 26, that led him to start out on the spiritual journey that he continues on to this day. “It was a sort of wake-up call. I discovered the truth; I found that my fundamental faith was drawn from the Bible; and I am now guided by the Holy Spirit and Holy Ghost. Jesus is the Christ.” Having heard a ‘Voice’ that told him: ”Don’t you never drink, smoke or defile your body in any way. There’ll be a work for you to do when you get older,” Dennis is now a devoted follower, recognising William Branham as the seventh Messenger, the end-time “Elijah” prophet of the Laodicean Church age, who also claimed to have experienced prophetic visions.

“Once when I saw the light and the truth, I felt I was free. My business went down and so did my relationship with my children’s mother, but I was no longer a slave to either. Initially, yes, I sometimes felt alone but at the same time, I felt closer to God.”

Dennis abandoned his possessions, the material no longer having any significance for him, and his desire to purify his life led him to take actions that might puzzle some and antagonise others, but Dennis feels certain that he is being led by the Holy Spirit and that his path is often a testing one. “You have to understand,” says Dennis, “that I have no respect for the ‘flesh man’ and his desires in me; I only cherish the spiritual me and I submit myself totally to HIS pre-eminence in my life.”

I asked Dennis how he managed to master the ‘flesh man’ within him; how did he quell his earthly passions and desires? “That is a daily battle. I feel I am a prisoner of my own flesh and I strive to escape from it often, but sometimes I fail; I see this as a The Trial, The Test and all I desire deep inside me is godliness, charity and holiness.”

I ask if he ever woke up filled with doubts - after all, the world around him is so often diametrically opposed to the path he has chosen. Without the least hesitation and with a marked firmness in his voice, Dennis replies: “No, never. I believe that God does not make mistakes, and that I’m being led by the Spirit of Truth. I’m not a puppet, but I am a servant, and I submit to the Truth. If you choose to see me as a puppet, then I am a puppet by choice: I have allowed the strings to be tied to me. I know there is a new body waiting for me in the spiritual kingdom, a heavenly body, to live in for another thousand years.”

I was slowly beginning to apprehend why the ascetic life - living in a garage, extremely modestly, without possessions or comforts - was not a problem for Dennis. If the urban landscape of Brixton contained any natural caves, doubtless Dennis would choose to make his home in one, and to live like a medieval hermit. Except that Dennis is no hermit; he continues to be a social creature, he hasn’t cut himself off from the people he grew up with; and he still loves people. He is still a barber too but now he works at the Stockwell Park Community Trust, where he cuts hair for free or for anything that people choose to give him. He remains a member of this rich, vibrant community, a community overflowing with the usual passions, desires, wants and challenges of life; it must take tremendous strength of character not to pitch in, not to let the ‘flesh man’ free to roam again.

Will Dennis succeed in his spiritual quest, I wonder? Towards the conclusion of the interview, I asked Dennis where he saw himself in five years’ time; hesitating a little, he replied: “I see myself in retirement from my labours, perhaps as soon as the end of this month. I do not see myself on this planet, for there is something in the Bible that speaks of going away; it is called RAPTURE. In terms of me as a ‘flesh man’, I feel that I have planted my seed, so life will carry on; there is not much more to do for Him. And I believe the RAPTURE is imminent.”

I asked Dennis rather bluntly if he was confident that he would be one of those to rise upwards to Heaven in the Rapture, and to join Christ for eternity; this time, he replied without the least hesitation: “The Holy spirit has indicated that I am one of them. I denounce the world.”

Interview date: 29th April 2017

Text edited: 17th June 2017