Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? LIVING ON THE WATER

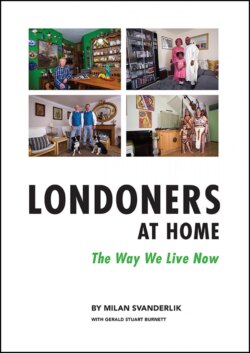

ОглавлениеJustine Armatage and Charlie Finke (with Valentine, the dog)

Justine and Charlie are both accomplished musicians and describe their longitudinal existence on a narrowboat, on the River Lea, as part of a community of ‘off-grid’ people. Inevitably, certain types of people tend to be drawn to the watery lifestyle - environmentalists, a surprising number of LGBT people, sometime travellers, and lots of other folks who don’t quite relish mainstream living in the little boxes of the new nappy-valley estates, or who simply want to be closer to nature and to the water. Perhaps above everything else, the astronomical cost of London housing has contributed to the ever-increasing number of people who choose, or who are forced, to take to life on the water; many of these people simply cannot afford to buy conventional homes. It is estimated that over 15,000 people now live, all the year round, on the UK’s numerous narrowboats and the numbers are rising.

Photograph: Justine Armatage on the left, Charlie Finke on the right, and Valentine in the basket. (Photography: 13th November 2016)

The full story:

Instead of living in a flat the size of a shoe box, Justine Armatage and Charlie Finke live on a narrowboat, moored in north east London’s Lea Valley. Having photographed them in late November 2016, I returned about a year later to interview them at length. Wishing to know a little more about Justine, I took the liberty of asking her first about her background: “Milan, yes, you can call me a true Londoner. I was born in Barnet, in north London. My father was a jazz drummer and my mother was a teacher. They split up when I was still young and, while my brother and I lived modestly with our mother in a council flat, Mum made sure that I still had my piano lessons and my ballet classes - something of a middle-class thing going on there, I suppose.” Justine smiles.

Justine went to a local primary school in Harrow, from where she progressed to secondary school, though the time she spent there was not entirely fruitful. Justine continued: “Once I was a teenager, I just gave up on school; all I wanted was to be a punk and to join a band. Of course, by that time, I had acquired quite solid, classical musical foundations, both in piano and violin, but then other music started to occupy a bigger part of my life. At the age of 15, I joined a horrible punk band; I just wanted to make a racket, to churn out lots of angry noise. I loved it. We all loved it - this was the age to do it, the time when we all wanted to be punks.”

Justine has a well-deserved reputation for projecting an image of herself that is always considered yet always original. She continued: “The punk trend influenced me a great deal: I often had my hair an extraordinary colour and wore vintage mixed with charity shop clothes which made me stand out. While my father proved pretty phlegmatic about my being in a band, I always knew that my mother would have much preferred me to go on to music college and become a classical musician. Unfortunately, I felt strongly otherwise.”

I asked Justine how she had progressed from that point and she burst into laughter: “Milan, I don’t think I progressed at all! I am still in the same boat, if you’ll pardon the pun.” If she didn’t progress, Justine certainly moved on, becoming a member of a succession of bands until she began to get bored with it all; at that point, she returned to classical music. She attended college and arranged private tuition in classical piano from a concert pianist, in return for which, she taught his young son. She also did a number of temporary jobs, including a stint as an art school model, but came to realise that she both enjoyed, and was quite good at, teaching. So, from her early ‘20s, she has taught piano; indeed, she continues to do so, right up to the present. “Then, when I was about 30, Charlie came for piano lessons and, as they say, the rest is history.”

I then asked Charlie if he would tell me something about himself, about the years before he decided to spend his life in the same boat with Justine. “Unlike Justine, you could have called me a country boy - perhaps not any longer, but I was born in a small village in the Midlands. There were two of us children, me and my older sister, and looking back on our childhood, I especially enjoyed all the fun and freedom we had in the many open spaces around us - I think fondly about those days even now. I suppose you could have called my parents ‘aspirational’: my mother was a teacher but my father considered himself to be just a bit posher than he actually was. He had indeed gone to a minor public school and at one time, he certainly considered himself to be better than anyone else. But sadly, he wasn’t particularly successful professionally and worked mostly as a door-to-door salesman. Consequently, I went to the very ordinary, local comprehensive.” I asked Charlie how well he’d done at school: “Badly, Milan, but having said that, I did enjoy some of it, especially the English and Art. Unfortunately, it was the sort of school where you had to be either academic or good at fighting, and if you weren’t one or the other, you didn’t get much respect. There was plenty of bullying, unless you were clever and cheeky, and that was me. Together with a few kindred spirits, I used to cause trouble in class, and through that mechanism, we were able to manipulate our popularity - it proved to be an effective way of not getting beaten up, but it was not the best place to be as a teenager.”

“However, I wasn’t just a troublemaker, I was also a keen cyclist in my teens; at every opportunity, I used to cycle off to the nearest town, which happened to be Northampton. I observed life and people; I spent ages looking at records, listening to music, and dreaming of having a nice stereo of my own. This is how I spent my Saturdays, days that helped me stay a bit more in touch with the world. The kids in the town simply looked so cool - compared to them, I must have seemed a provincial farmer’s boy. So once I reached the grand old age of 17, I moved out of the village and rented accommodation in the town. It was there where I went to college and did the Art Foundation Course, supporting myself by continuing with my job on a farm.”

Having done well on his Foundation Course, there was only one obvious choice for Charlie - head south to London and enrol on a degree course at a reputable college of art; he chose Hornsey, well-known for its progressive and experimental approach to art and design education. “I did well there, especially in the area of painting, life drawing and landscape, though once again I was going against the grain - almost everyone else was so deeply into conceptual stuff, my work seemed almost iconoclastic! Mind you, I did branch out into abstraction later on.”

Charlie continues: “Coming down south, being in London, felt like walking on air. Every night I was out; something incredible appeared to happen almost every day; and I tried to see as many bands as possible. London really was the place to be.” The BBC’s John Peel proved to be a great influence on Charlie’s development as a future musician. “Absolutely everyone of my generation would listen to his wonderfully eclectic selection of music. As a northerner, he wasn’t the least bit ‘London-centric’ and played requests from people from all over the country. He introduced me to many different genres of music, as well as a great range of artists; he didn’t merely play bands from all over the world, he played bands from the Midlands too. These were often bands that I already knew, bands that I reckoned were good, bands that I wanted to be like. I also saw what was the increasingly well-established route into pop music through art college; everyone who was cool had taken that path.”

I asked Charlie how he’d actually come to be a musician, and later on, a singer: “Well, a few of us in College decided to give it a go. We bought instruments and taught ourselves how to play. I started off with the base guitar, which I bought in London, the cheapest one in the shop. But we were keen and quite soon, we were able to start rehearsing together and I felt instantly liberated. We called our band, Hinnies and we performed extensively - we even got taken on as a support band for Blur, during one of their European tours. With the benefit of hindsight, I’d have to admit we were rubbish, but at the time, it was undoubtedly an exciting period in my life. Between 1990 and 1993, the Hinnies even managed to release three records.”

“While I think I did quite well, I was never entirely satisfied with the music I wrote end performed. And in the end, it all came crashing down simply because we weren’t really very talented - we were just enjoying ourselves. However, those three years gave me a taste for music and for performing. Later, I switched to a proper, ‘fuck-off’, post-punk, rock band called, Penthouse. I was their lead singer and during seven or eight years, we toured the world and made three albums. While we didn’t make a single penny out of it, we had a great time and I made lots of friends and many contacts. I learned to have great respect for all those artists who are living on the edge, and I realised that this was the place to be. This was also the time when I met Justine.

Justine and Charlie are both accomplished musicians and, having each been members of successful touring bands in the past, they have for 10 years now had a band of their own, The Cesarians, and the band not only tours in the UK but also in Belgium, Italy, France, Germany, and Austria - it’s especially welcomed by discerning fans in Switzerland. Charlie says, with a smile: “What we play is very much alternative pop, with jazz and classical influences, so we do have quite a broad appeal and we always try to maintain a strong sense of individuality.” Both of them are wonderfully stylish too, with attire that references punk, alternative, and classical influences while remaining firmly grounded and delightfully unpretentious. They have lived on the water for over 10 years together, now sharing the boat with their dog, Valentine, and cat, Elvis, who proved a bit camera-shy on the day of the photo-shoot.

On visiting Justine and Charlie, the first thing that would strike you is that living on a narrowboat is, as the name itself rather implies, very much a longitudinal existence, although a surprising range of home comforts seem to have been fitted in through the use of the most ingenious design solutions, despite the confines of the long, narrow interior. They have even managed to fit in a piano and live music can often be heard emanating from their windows, windows that are no more than an oar’s length away from the canoes and rowing boats that frequently go swooshing past.

Like all the folk whose boats are moored along the same stretch of river, Justine and Charlie belong to a community of ‘off-grid people’, that is, people who generate their own electricity through the photovoltaic cells on their roof. And what is immediately apparent is that ‘off-grid’ is exactly what this great community is. Inevitably, certain types of people tend to be drawn to the watery lifestyle - environmentalists, a surprising number of LGBT people, sometime travellers, and lots of other folks who don’t quite cherish mainstream living in the little boxes of the new nappy-valley estates, or who simply want to be closer to nature and to the water. Justine adds: “By now, our neighbours are well accustomed to seeing us walking along the towpath in our somewhat outré performance attire, as we head off for a gig.” They are a well-established part of this unorthodox world which, like a colourful, bohemian ribbon, lines the banks of London’s River Lea.

Perhaps above everything else, the astronomical cost of London housing has contributed to the ever-increasing number of people who choose, or who are forced, to take to life on the water; many of these people simply cannot afford to buy conventional homes. It is estimated that over 15,000 people now live, all the year round, on the UK’s numerous narrowboats and the numbers are rising. “Not many years back”, Justine says, “there were only a few of us on this bank; now, the line of boats stretches far out of sight.”

After a short, dormant period, The Cesarians are active once again and performing, with their European fans keenly awaiting their return. But a crust has always to be earned: while not creating music, Justine gives piano lessons and Charlie goes labouring, though he says optimistically: “Every time we write a new song, we are totally confident that this will be the one, the one that gives us our break. And every time we think that this is the one that will make our fortune, I dream of never again having to pick up my bag of carpenter’s tools and head off to a windswept building-site somewhere. I carry on in the hope that, one day, someone will hear our latest song and go ‘WOW’, and all our past work will then be rediscovered too and that will be seen as equally good. Milan, I have no shame and no regrets but I do continue to be a little surprised at my own level of optimism; still, one day …” Charlie laughs before continuing contemplatively: “I do wonder sometimes if perhaps I wouldn’t be writing the sort of songs I write if we didn’t live the kind of life we do. I suppose I must be the eternal optimist. Mind you, if there’s something that does keep me awake at night, something that even I can’t be optimistic about, it’s Brexit and the fear that should we actually, finally part company with the EU, Britain could find itself increasingly abandoned, forgotten in the stagnant backwaters of Europe.”

Interview date: 13th November 2016

Text edited: 25th November 2016

Text re-edited: 25th January 2018