Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHO do we live with? SINGLE FATHER

ОглавлениеTimothy Alfred Bentler-Jungr with Miroslav Aleksander Bentler-Jungr

Following his mother’s tragic, early death, teenage Miroslav is being raised a little unconventionally by his writer father, Timothy, who is determined to see him develop into a well-travelled, well-rounded young man, capable of taking on all the challenges of life that await him. In response to the question most frequently put to single parents, about the lack of a male or female role model in their child’s life, Timothy says he doesn’t think much of the idea that children must have a male and/or female role model. He doubts whether children actually need these kinds of stereotypical role models to grow up into well-balanced adults. In any case, there are plenty of women in Miroslav’s life; there always were and there always will be.

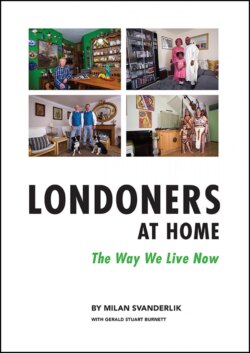

Photograph: Timothy Alfred Bentler-Jungr with his son, Miroslav Aleksander Bentler-Jungr at their London home. (Photography: 12th April 2017)

The full story:

The great majority of articles written about single parents focus on the predicament of the mother and I, too, propose to cover this topic once I find a willing volunteer. However, I was equally keen to hear about the experiences of a lone father raising his child and I was therefore very pleased to be invited to photograph, and interview, Timothy Alfred Bentler-Jungr and his son, Miroslav Aleksander Bentler-Jungr, aged 13, at their south-west London flat, not far from the Thames.

“I was born in America, in a very rural part of Minnesota; there, I grew up in a land of farms, lakes and woods; even the towns were very small.” I told Tim that this sounded idyllic, to which he replied: “Nowhere is ever idyllic but it certainly was a good place to grow up, in a big extended family, in a place where everybody knew everybody else and everyone’s business was common knowledge, which can be both a good thing and a real headache.”

“I admit I was pleased to leave, though I do return every year; while I still have family and a house in Minnesota, I am more comfortable living elsewhere. In fact, I have lived in five or six different countries since then, over a period that is now significantly longer than where I lived as a boy. And, in marked contrast to my childhood existence, I have lived mostly in big cities, like Washington, London, and Tokyo.”

I asked Tim if he ever dreamt of returning to the farms, lakes and woods: “Sometimes I do,” he says, “and the life of a hermit does have some appeal for me but such longings are not realistic; I am essentially a metropolitan creature now and I’ve learned how to make my home wherever it is I’m living at the time - I’m a sort of outsider everywhere but a bit of an insider too. I feel that we decide for ourselves where our home is. For example, 30 years ago, when I was 25, I lived in Japan; I taught English there. At that time, you were always conspicuous as a foreigner; it made you feel that you were always visible, that you couldn’t just blend in. While such feelings could be liberating, they were sometimes oppressive too. Interestingly, it’s not like that any more: when I returned last year, it was clear that people are much more accustomed these days to having foreigners living amongst them, and foreign faces no longer produce the palpable reaction they once did. Living there today would be far easier for an outsider.”

“When I was living in Japan, I met my wife, Carolyn, who was also working there; she was teaching too but she also wrote textbooks for a local educational establishment. We were together for twenty years, during which time she built a substantial career for herself within the World Bank, while I mostly worked from home, writing. She travelled a great deal on business and was located in a number of different countries: we lived in Japan, here in England, in Taiwan, and in Serbia. We had just moved back to the US from Belgrade, in Serbia, and we were about to move again, this time to the Middle East, when Carolyn had a sudden heart attack and died; she was only 42 and our son, Miroslav, was but four years old.”

In the light of this devastating information, I hardly dared to ask how things had changed for him after Carolyn’s death. After some hesitation, Tim told me: “I was already the stay-at-home parent, as it was Carolyn who had the high-powered job and the bigger income. I was a writer and I worked from home; this was how things had been for many years. So I was already established as the primary carer for our son, which is not the case with most fathers. After losing Carolyn, I was fortunate in not having to return to work in an office; I could be a parent first and a writer second.” I asked Tim if, after Carolyn’s death, he felt the need to make major changes to his life with Miroslav, to alter his life plans. Laughing uncomfortably, he responded: “Mostly not: though lots of people talk about making plans for the way they’ll raise their children, to be honest, I’m not sure that there’s really much substance in any of that. Generally speaking, I think most parents just respond to what their children say (or communicate) they need. If you had a blank slate, you might perhaps be minded to think of strategies, to devise a ‘child-rearing master-plan’, but no child is a blank slate, you have to work with the child you’ve got. The difference I felt after Carolyn died was simply this: I no longer had a partner to bounce ideas off; at the end of the day, I could no longer converse with someone close and dear to me, the mother of my son; I just had to work everything out for myself. But in my case, especially, it meant that my relationship with my son become exclusively one-to-one, almost a partnership, you might say. As he grew up, Miroslav inevitably became more involved in making choices about his life, much more than many children of his age are. I clearly remember old friends of mine in the States telling me that they couldn’t do what I was doing, bringing up a child on my own, and I said: “Of course you could; you just get on and do it, you have to, and you figure it out the best way you can!”

I put to Tim the question that is most frequently asked of single parents, about the lack of a male/female role model in the child’s life; hesitating just a little, Tim replied: “I don’t much like the idea that you need a male or a female role model. I don’t consider myself a ‘typical male’ anyway, whatever that might be, nor could I say that my wife was a ‘typical female’; I don’t think children need these kinds of stereotypical role models. In any case, there are women in Miroslav’s life, there always were. I remember the time when gay marriage was being discussed, and people were saying, ‘a child needs a father and a mother’ and I remember saying to someone, so if your wife dies, does that mean you should give your child to another couple, just so that he or she can be raised by both a man and a woman? Of necessity, children grow up in all kinds of circumstances and as long they are loved and cared for, and have a sense of belonging, they will grow up into well-balanced, adult human beings. I really don’t feel you need a mother figure and a father figure to raise a child.”

“It has been almost 10 years since Carolyn passed away and we have learned to live as we do - it is now quite hard to imagine living any other way. We’ve managed together and we’ve worked things out together. When Carolyn died so suddenly, I was in shock, of course I was, but I still had to get up and feed the kid. Sometimes, I just wanted to sit in a chair and cry, or just sit and do nothing at all, but that option was not available to me: at his age, Miroslav was entirely dependent on me, so I had to be both mother and father, and I got on with it as best I could. It was as simple as that. A child makes you carry on but it also enables you to carry on. Now when Miroslav was no longer a little boy but started to turn into a young man, a young man who, quite understandably, would begin to seek his independence, I started to wonder what my future would be then. For years, we have been a pair, but the time will come for us to part, and that is the way it must be. Just as I left my little place in the woods, all those years ago, when the time was right for me to go, so will he, and then I will be on my own - after all, so-called ‘empty nest syndrome’ is experienced by most parents. My job will have been done, perhaps it already is.”

During the last three years, Tim and Miroslav have led a rather unconventional existence; they have travelled extensively and lived in many different places. I ask what was the motivation for this unusually peripatetic lifestyle. Tim explains: “Carolyn and I lived all over the world and we always had the idea that Miroslav should grow up in an international environment; after all, we were an international couple ourselves and, with our own family heritage being a mix of several nationalities, that made good sense. In the years immediately after my wife’s death, I felt that the priority was to maintain as much stability for our son as possible, so Miroslav attended a local elementary school in the States, but when the time came for him to start middle school, I thought that this would be a unique opportunity to take three years out and to travel extensively. Miroslav could then return to the US, enter High School, proceed from there to a university, and then on to a job, his life back on the normal track. But I saw this time as a one-off opportunity to make a change, to do something different at the moment in Miroslav’s life when this was possible.”

So Tim had something of a ‘plan’ for Miroslav after all! In the light of this, I ask Miroslav, a highly articulate young man, to tell me something of the places he’d travelled to: “We came here to London first; we have a flat here and my mother’s sister, Aunty Barb, lives nearby; so this has been our sort of base. From London, we first went to Istanbul, in Turkey, staying there for a month. After that, we travelled to Iberia, visiting the great cities of both Spain and Portugal. Italy, France, Israel and Japan followed. Then … Well, to be quite honest, it would be quite hard, and probably a bit tedious, for me to list every country we’ve been to, well over 30 by now I should think, but we’ve certainly travelled extensively in Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia and South America. In all the places we’ve stayed, we spent large chunks of time, to get an idea of how it feels to live in a place, to see life there the way it is. Of course, we also made a point of seeing all the principal tourist attractions as well. Initially, it felt strange to be on the move so much of the time, but gradually it began to seem normal,”

From these various journeys, Miroslav has regularly dispatched to London his own personal travelogues. From even a brief perusal of some of these well-researched and rather eloquently-written impressions of, and observations on, the many places that he’s been to, one can see that, despite his tender age (he is but thirteen) Miroslav already sees beneath the surface, beyond the obvious, and is able to compose mature pieces of travel writing that are not only informative but also hold the reader’s interest. Miroslav continues: “What I like particularly about Istanbul and Rome are the layers, the complex, multiple layers of history. I like the way these cities have grown over the centuries, constinually building new structures on top of earlier ones, so that newer worlds now exist above older, very different worlds. You can see how society develops too, how ideologies and religions are embraced and discarded, like Istanbul, going from Roman to Byzantine Greek to Ottoman Turkish, a pageant of Christianity supplanting paganism then being superseded itself by Islam. It is fascinating to observe how people have lived together and rubbed along with one another through these multiple veneers of civilisation.”

Tim elaborates further on the value of travel and the opportunities it provides for understanding different peoples and their histories: “I feel that acquiring the long perspective equips us better to live through a tumultuous present, like the period of turmoil that we are going through now, and teaches us that just as all good things must come to an end, so too will all bad things pass. Indeed, as we live and age, we ourselves are becoming part of that history too. Though these are our moments in time, they are essentially the same as those moments in the past, and in the future, that we know others have had, and will have. Our travels through the world are also, in one sense, travels through time and they can teach us how to keep things in perspective.”

“Miroslav has always been self-motivated: generally, without prompting, he will prepare himself thoroughly for our travels, so that by the time we arrive in a new country or city, he will know something about the people who will be out hosts and have a good grasp of their history. All I do is point him in the right direction and draw his attention to what I think might be useful reading material; after that, he does the rest. The older he gets, the less I have to do. Because I know how methodical he is, and how well he assimilates what he learns, I expect that one day he will himself become an exceptional traveller.”

At the end of the forthcoming Summer, father and son aim to return to Virginia, where Miroslav will begin his four years in High School. His own experience has taught Tim a harsh lesson on exactly how fragile human life can be, so he says: “This really is as much as I feel I can plan ahead; after that, who knows. We shall wait and see what happens.” I asked Miroslav if, after these three fascinating years of travel, he is looking forward to a rather more conventional life, life under the same roof, sleeping in his own bed, day in day out; with a broad smile, he replies: “Yes I think I am, very much!”

Next week, Tim and Miroslav are heading off to the Balkans, to Serbia, which is not entirely terra incognita - years before, they had lived there as a young family - but it still remains one of the most turbulent parts of Europe, where West meets East and the tectonic plates of countervailing civilisations grind against one another, sometimes with appallingly destructive results. This is a critical line between peoples of quite different genesis; it can seem an impenetrable wall yet it also offers a gateway to an understanding of how twenty-first century European culture and mores have come to be what they are. Perhaps a sojourn on this great geographical, historical and cultural dividing line is an apt precursor to the new stage in both Tim’s and Miroslav’s lives: they are returning to the United States where violent political storm is everywhere and perhaps, after their extensive travels through the Old World, they will have acquired the perspicacity better to understand the New. Let us hope they can discern what is actually going on, make some sense of it all, and put it into some kind of perspective - perhaps in turn they might then help all of us here to understand a little better too!

After such an informative exchange, all that remains is for me to record my thanks, both to Tim and to Miroslav, for allowing me to photograph them and for letting me a little into their unusual lives; I wish them both all the very best for the future.

Interview date: 12th April 2017

Text edited: 28th April 2017