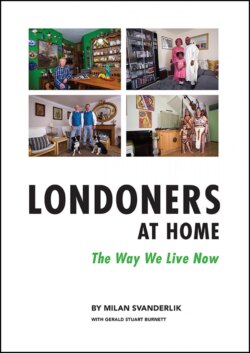

Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? LIVING IN A HOME FOR THE ELDERLY

ОглавлениеDiana Athill OBE

Diana Athill OBE lived past her 101st birthday at a home for the elderly in Highgate where, living comfortably herself, she raised quite forcefully the desperate state of social care for the great majority of England’s old folk who are denied the same standard of accommodation and care. Local authorities have seen their funding drastically reduced at a time when the demand for the provision of care for the elderly is rising exponentially and private providers are demanding significant increases in fees. This is what some would call the inevitable clash between market forces and the public interest, right in the middle of which are our unfortunate senior citizens, caught at exactly the time when they are most frail and in greatest need of well-funded, expert and humane care. In the case of domiciliary care, which is crucial in enabling the elderly to stay in their own homes, 95% of such care was directly provided by local authorities as recently as 1993; by 2012, this had fallen to just 11%. Nearly all these services have been privatised, largely taken over by private companies, and mostly operated for profit; if and when such profits can no longer be realised, the care service is simply terminated and vital provision is further diminished.

Photograph: Diana Athill OBE in her private room at the Mary Fielding Guild, Highgate Village (Photography: 8th February 2017)

The full story:

Diana Athill OBE, at the age of 99, kindly accepted my invitation and allowed me to photograph her in the residential home for the active elderly, where she lives in Highgate. Understandably, she is now quite frail but her mind is as alive and sharp as ever. Having been a well-known literary editor, with her own publishing house at one stage, she has worked with some of the most significant writers of the 20th century. She has worked for the BBC too and, in her own right, is a successful novelist and memoirist. Diana has lived a long, fulfilled, independent and exciting life; she has never married but has never lived in solitude by choice; she has never had children but has been able to maintain a dynamic and successful writing career right into her nineties - indeed, her most recent volume, A Florence Diary, was only published in the Autumn of 2016, when she was already 98.

Diana now lives in a pleasant building, surrounded by a fine garden, in London’s Highgate Village; it is the property of the Mary Feilding Guild, a charity established in 1877 and one that prides itself on offering the elderly an independent life in a safe environment, with some provision of personal care, as required. The Guild encourages residents to maintain their outside interests and respects their privacy, while seeking to promote companionship and a sense of community - vibrant social, cultural and creative engagement is what the Guild seeks for its residents. During the photo shoot, Diana observed: “I love living here: I am able to continue to be active and still know that if I need any help, such help is available; all the staff are so kind and good to me. I also made many delightful friends here, almost at once - people from so many diverse professional and cultural backgrounds. One is never alone unless one chooses to be.”

Diana’s decision to move into what she thought of as an ‘old people’s home’ was never easy. In her recent memoir, Alive, Alive Oh!, she writes: “Few events in my life have been decided by me. How I was educated, where I have lived, why I am not married, how I have earned my living: all these crucial things happened to me rather than were made to happen by me. Of course an individual’s nature determines to some extent what happens, but moments at which a person just says, ‘I shall now do X,’ and does it are rare - or so it has been in my life. Perhaps my decision to move into a home for old people is not quite the only one, but it is certainly the biggest.”

Diana writes touchingly about how difficult it is to face the day when you must move out of a fine home, lovingly created over the years and filled with memories and beautiful possessions; above all, she speaks of the wrench of leaving behind hundreds of books and paintings, to move into a single room that can only accommodate a few personal possessions - some books and a few pictures. But her memoir is not steeped in regret; she accepts that her move was not only sensible but also necessary and, all things considered, she is happy in her new home. Significantly, she writes: “Newspaper stories about nasty happenings in homes for old people, when untrained, probably underpaid and obviously ill-chosen staff have bullied and manhandled helpless residents, have been shocking, but no more so to us, who are residents in such a home, than to outsiders. Being old ourselves, we naturally feel for the victims, but apart from that, such stories have nothing to do with us. Our home - and no doubt the same could be said of many others - is one in which such happenings are unthinkable. Basically, this is because ours is not one of the many run for profit.”

Diana Athill touched upon what is a crucial issue in what we in Britain now tend to call ‘Social Care for the Elderly’. Since 1979, there has been a substantial shift in this sector, where the provision of residential care, either by local authorities or the NHS, has been reduced from nearly 65% to 6% (as at 2012). In the case of domiciliary care, 95% of which was directly provided by local authorities as recently as 1993, by 2012, this had fallen to just 11%. All these services have been privatised, largely taken over by private companies, and mostly operated for profit. And this sea change has been characterised by a growing role for big ‘care companies’, with fifty or more homes, to the detriment of small, family-run businesses - five large chains now account for 20% of provision and this figure is expected to rise.

Many of these ‘care companies’ have attracted investment from hedge funds, off-shore trusts and other financial entities that expect speedy returns and unrealistically high profit margins. To achieve these returns, the most elaborate accounting mechanisms and company organisational structures have been put in place. The properties and other fixed assets are often transferred to off-shore holding companies (these pay no UK corporation tax) with the UK-based ‘care companies’ employing the staff and providing the actual service; these companies are then saddled with such extortionate rents and maintenance charges, levied from abroad, that they only just break even - they make no profit and so pay no UK tax either. And so tight are their margins that they are consequently obliged to employ untrained or poorly trained staff, on oppressive contracts and poverty wages - such staff are often forced to adopt self-employed status and are thus denied pensions, holiday pay or sick pay.

In a highly respected report from the Centre for Research in Socio-Cultural Change, it is unambiguously stated: “The report illustrates the argument about debt-based financial engineering through a detailed analysis of the largest chain, Four Seasons, which is owned by Terra Firma Private Equity, and controls 23,000 beds. The chain consists of 185 companies, tiered in 15 levels through multiple jurisdictions, including tax havens, which minimises tax liability for the owners and creates an opacity which is not in the public interest.” The report continues: “The accounts of one upper tier holding company (Elli Investments) raise issues about what is going on. For example, media reports note £525 million of external debt; but Elli’s accounts show an additional £300 million of intra-group debt charged at 15% which more or less doubles the annual interest bill (before profit can be made) to more than £100 million.”

Local authorities have seen their funding drastically reduced (by almost 40% during the last parliament, broadly speaking) while the demand for the provision of care for the elderly is rising and private providers are demanding significantly increased fees. This is what some would call the inevitable clash of market forces and the public interest, right in the middle of which are our unfortunate senior citizens, caught at exactly the time when they are most frail and in need of humane, expert and well-funded care.

In view of the increasingly parlous condition of social care for the elderly in Britain today, should we not be questioning the basis upon which this care provision is now made? Should care homes for old people, or the providers of peripatetic carers for the elderly still living at home, be supplied by big private companies whose only interest is profit and who take the most elaborate and questionable steps to ensure that the profits that they make escape UK taxation? Is it not the case that most people in the UK see the provision of health and social care as a matter for the state, to be run as efficiently and cost-effectively as possible, certainly, but not to pour money into the coffers of off-shore companies? This must surely be a pressing matter for public debate and for Government to resolve in such a way as to offer adequate, decent provision for an expanding elderly population.

You might care to read some of Diana Athill’s excellent and highly-regarded books, eg:

Alive, Alive Oh!: And Other Things That Matter

Somewhere Towards the End

Instead of a Book: Letters to a Friend and others

Interview date: 8th February 2017

Text edited: 13th February 2017

Update (January 2019)

We have to report the sad news that on Thursday 24th January 2019, Diana Athill passed away at the great age of 101; She will be greatly mourned by her family and by everyone who knew her.

Born: 21 December 1917; died 23 January 2019

May she rest in peace.