Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? I, DANIEL LUL, FEAR LOSING MY HOME

ОглавлениеDaniel Lul

Daniel became desperately ill with meningitis; as a result of the infection, he finally had to have both legs amputated. While he made a long, gradual recovery from the illness, struggling to come to terms with the terrible loss of his legs, and learning slowly and painfully how to stand and walk on new, prosthetic limbs, the evil workings of the benefits system threatened to deprive him of the welfare payments that were essential for him to keep his home, a flat specially adapted for wheelchair users. He is safe for the moment but should the DWP succeed in doing its worst, and should you ever come across young Daniel turned out on to the street, on a rainy night, in his wheelchair, with his prostheses in a bag beside him, together with his few other worldly goods, you must refuse absolutely to stay silent; you must howl in rage at our political masters for having wilfully cast aside any kind of moral compass and for dehumanising our society through the dogmatic promotion of a creed that only allows the fittest to survive. Daniel’s crime was to be taken seriously ill with meningitis, a disease that might easily have robbed him of his life, not just his legs. Having worked for seventeen years, paying his taxes and making his National Insurance contributions, might he not have reasonably expected to be given support during the inevitably long period of his recuperation, a period in which he had to learn to walk again? If the DWP succeeds in pulling the rug from under his feet, his amputated feet, it will be an act of unimaginable cruelty, a crime against humanity that should make every one of us hang our heads in shame.

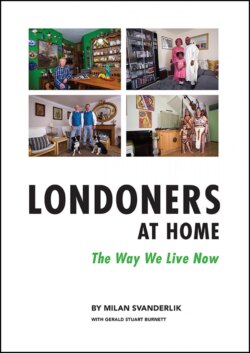

Photograph: Daniel Lul at the new home he fears losing. (Photography: 10th May 2017)

The full story:

A few months ago, I went to see Ken Loach’s latest film I, Daniel Blake, which won the director his second Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and was referred to by the New York Times as ‘Daniel Blake, Stuck in the Bureaucratic Hamster Wheel’. The film takes us through the recent life of a 59-year-old carpenter from Newcastle who is recovering from a major heart attack; on medical advice, he is not to undertake any work during what will be a substantial and necessary period of recuperation. We watch him as he struggles through the maze of regulations, an appalling nightmare of bureaucracy, that the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) has seemingly created for the sole purpose of frustrating and degrading claimants, and minimising their claims for benefits to which they are completely entitled - benefits that are crucial for their survival.

It is quite plain that Daniel is not yet fully recovered from what has been a life-threatening health crisis and although his doctors have clearly stated that he is not well enough for work, he is nevertheless assessed as being fit for employment by one of the privatised government agencies now appointed by the DWP to carry out such assessments. Before our very eyes, we see a decent human being, who has worked all his life and paid all his dues, destroyed by a process that is cruel and vindictive and where common humanity seems to have no place.

At the end of the film, as if to demonstrate just how ill he really is, Daniel Blake collapses at his appeal tribunal and dies on the spot. When the cinema lights went up, most people remained in their seats, motionless, shocked and appalled by the terrible injustice that they had just witnessed; some people were actually crying, while others stared aghast into the blank screen. Someone commented angrily, “How can this be done in our name?” but one thing is certain, those who shape the policies never go to see films like this, having no wish to see so starkly the awful consequences of the decisions they take. For myself, I felt numb; my first thought on passing out of the cinema and into the cool drizzle of a London evening was, ’I need a drink!’ The film is a piece of fiction, of course; thankfully, there is no real Daniel Blake, but there are too many claimants exactly like him.

Little did I imagine that, a matter of a few weeks later, I would be standing in front of the door of a real Daniel, Daniel Lul, who is grappling with an almost identical claimant’s nightmare right now. This Daniel is a tall, handsome, smart-looking young man with the sort of face that gets noticed in a crowd. He greets me wearing shorts and a broad, friendly smile, as he balances, slightly insecurely, on his two new prostheses - he is a double amputee. Daniel’s flat is almost minimalist, though perhaps this is not surprising given that he only moved in two months earlier and the builders are still working outside, putting the final touches to this newly-built block in Borough, in the south-east of London.

Daniel speaks with the merest hint of a foreign accent but his conversational English is almost perfect. I asked him to tell me something about himself and his background, which he kindly did: “I was born in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, where my father was working, but we considered ourselves to be Italian, Italian was certainly the language we spoke at home. Both of my parents were born in Eritrea, formally part of Ethiopia, and though my grandfather was Italian, my grandmother was Eritrean, hence my olive skin colour. Eritrea was an Italian colony for quite a long time so a mixed Italian-Eritrean heritage is not uncommon.”

“My father was a nautical engineer and as he would go wherever there was work to be found, I first went to school in Saudi Arabia where we happened to be at the time, though the school was within the international compound where we lived. Most of the teachers were Americans, as were the majority of my schoolmates, so English quite naturally became my second language. It was truly an international community: in addition to lots of Christian Americans, we lived amongst Muslims from Lebanon, Pakistan and the Philippines; there were even some ‘proper’ Italians too. As you can see, during my formative years, I was exposed to a great variety of people from diverse backgrounds and I can honestly say that, from the very outset, I felt comfortable in that kind of environment, something I rediscovered in London, many years later.”

Daniel continued: “When I was nine, our family moved to Modena, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, near Bologna - this was a sort of return to the Mother Country where I had never actually lived before. In Modena, I continued my education, finally graduating in Arts. While the area was lovely and it was certainly a pleasant place to live, I always had the feeling that it was a bit of a provincial backwater, though perhaps some would say that’s what gave it its charm.”

“When I was 23, I came to London for a six-month visit, to work and to brush up my English. But once I was here, I discovered the joy of living in a vibrant, diverse and exciting city, a city that never seemed to sleep. As an unattached young man, I was free to throw myself into London life; I made many friends and pushed the boundaries as often as I could. And somehow, here I am still, eighteen years later, with my six-month return ticket now most definitely expired.” Daniel laughs. “I worked mostly in the hospitality industry but then, after a number of years, I made a switch, becoming a charity fundraiser. It seemed that I had the personality for it, the ability to encourage individuals and companies to give financial support to organisations that look after people unable to help themselves. I shared a flat on the top floor of a Victorian building in Camberwell. Life was kind to me and it felt good to be alive.”

Daniel continues his story: “Then, on one unremarkable weekend in August 2015, as I was returning home from friends in Ealing, I suddenly felt exceptionally tired so, wanting to be fresh for work on the Monday morning, I decided to go to bed early and have a good night’s rest. I don’t actually remember very much after that, to be honest. My flatmate found me in the middle of the night, in the bathroom, where I had fallen with something of a crash. I vaguely remember the paramedics attending to me and wondering what all the fuss was about; then I remember finding myself in hospital and wanting to get up and to go home - after all, I thought to myself, I had work in the morning. Then there was darkness, a darkness that lasted two weeks, though it might as well have been an eternity.” Daniel was indeed in a critical state: he was in an induced coma, having been diagnosed with Meningococcal Meningitis and Septicaemia, both truly life-threatening diseases. His body was awash with intravenous antibiotics, he was heavily sedated and stuffed full of painkillers. “When I eventually opened my eyes, I saw friends gathered around me - even my brother from Italy was there - so I realised that I must have something that was life-threatening but I didn’t know what it was. I was high on a cloud of morphine and I’m sure I must have talked complete nonsense, yet I do remember distinctly worrying about my rent for the month - there was £1,000 due that I had to pay. As I was single and self-employed, I had no-one to take care of such things.”

While he was worrying about practicalities, Daniel did not fully realise that the septicaemia had caused gangrene to develop in his legs and that his arms too were turning black. Daniel says: “I knew that I was seriously ill but I was happy that I was still alive, that I seemed to have made it through. I was in hospital for two and a half months altogether but even after that length of time, when I was discharged, my arms were covered in sores, one of my fingers had been amputated and both my legs were gangrenous. At home, I was bed-bound for two months in my top-floor flat, from which I had to be carried down and back up again by the paramedics, so that I could attend for my regular visits to the hospital. The nightmare continued, but at least I was alive.”

“Despite the doctors’ best efforts, in January 2016, they told me that I would need to have both of my legs amputated below the knee. I was just 40 and my life as a severely disabled man had begun in earnest. After the surgery, I remained in hospital for another two months and was then transferred to an amputee rehabilitation unit for seven more weeks. There I was fitted with my new, artificial legs, my prostheses, and there I had to learn how to walk again, how to take my first steps. Oh, how we take our limbs for granted …” Daniel exclaims tearfully.

It quickly became clear that, now he was mostly in a wheelchair, for Daniel to return to living in a top floor flat was out of question. Only then, did he begin to experience at first hand the harsh reality of the tattered remnants of what we used to call the Welfare State, before it began to be meticulously and deliberately dismantled.

“I applied for social housing, for accommodation that would be more suitable for me, a flat that was wheelchair accessible, but I was quickly informed that I was ineligible for such accommodation; to qualify, I would have had to be resident in Southwark for longer than five years. As I had only lived in the Borough for three years, I was asked to go away. Then, with the help of a Southwark councillor, I was encouraged to submit a request for accommodation through the Homeless Team, so I did, and thankfully my request was accepted.”

Of course, there is an acute shortage of all kinds of accommodation in London and because Daniel needed to be close to the hospital (he was still very ill and required constant observation) the search for somewhere suitable was made even more difficult. A ground floor room was found in a local hostel but the doors there were discovered to be too narrow to admit a wheelchair.

After more struggle, a suitable temporary place was finally found for Daniel and he lived there for eleven months, attending the hospital for further procedures and for continued monitoring. The septicaemia had not only affected Daniel’s limbs and other parts of his body, but it had also damaged his hearing. He was gradually learning how to walk on his artificial legs but the process was slow and often very painful; it was something that would simply take time.

Too sick to work, Daniel was receiving a number of benefits: the Personal Independence Payment (PIP, to help with some of the extra costs caused by long term ill-health or disability); Employment and Support Allowance (ESA, a benefit for people who are unable to work through illness or disability); and finally, a modest Housing Benefit (to help with paying part or all of the rent for people on low incomes). Daniel is a fiercely independent man and, having worked all his life, he was keen to return to work and to support himself.

In order to get himself back into the ‘world of work’, for seven months now Daniel has been doing voluntary work for a charity that looks after disabled people; he does there what he knows best how to do, he raises funds for them. He comments: “But I have to confess, I can only do this on days when I feel well enough, and on some days, I can only manage a few hours. Occasionally, I simply have to phone to let them know I won’t be coming in, because I feel so low or so unwell. They are very understanding, and of course, I am only a volunteer, but no normal employer would put up with this. So, as far as I can see, I am simply not yet well enough to return to full-time employment but I am confident that I will get there eventually. I am determined to get my independence back.”

Two months ago, Daniel moved in to his new home; it is a bright, newly-built apartment, so new in fact that the builders are still finishing work on the pavements outside. The doors here are wide enough for his wheelchair, which is just as well, for he says: “I still spend most of my time here. On good days, when I feel up to going out on my artificial legs, I can perhaps manage to walk for about a hundred metres, then I have to stop, to rest and to adjust them; sometimes, I have to take them off while the pain subsides. On a bad day, when it’s warm and my legs are swollen, I can’t even put the prostheses on; or even when I do manage to put them on, if it’s a bad day, I only take a few steps and I’m in agony. It just takes time; things are improving, but I need more time.”

Daniel is still on lots of medication to control his many symptoms. He suffers from terrible ‘phantom pains’ in his non-existent legs; he still has terrible nights and sometimes wakes up feeling so depressed that it’s hard for him to face the day. “Then I remember, I am alive!” He says this seeming to radiate with an energy that is almost tangible, but when I look into his eyes, all I can see is fear and apprehension.

Having moved into his lovely new home, where he hoped to be able to start gradually rebuilding his life, Daniel has discovered that he may find himself on the street, homeless. The glasses that his dear mother has sent over from Italy, a gift for his new home, may never get unpacked. Daniel is already £700 in arrears with his rent because both his ESA and his Housing Benefit have been stopped, following one of those infamous box ticking assessments carried out by the Healthcare Assessment Advisory Service (HAAS); they declared him ‘fit for work’ and axed his benefits overnight. The fact that Daniel’s GP and his hospital specialists all confirm that he is genuinely not yet fit to work, seems to have no bearing whatsoever on the decisions made by the HAAS, a body amongst whose frontline staff no doctors are to be found.

The HAAS didn’t even bother to send him a letter confirming that he’d been declared fit to work, but when they phoned to inform him of their decision, they did offer him the opportunity to challenge their decision via the process of ‘Mandatory Reconsideration’. Daniel immediately registered his wish to have the decision reconsidered but before he could do this, and argue his case properly, he needed first to see the evidence upon which the decision had been based. In the Kafka-esque universe that is the Department of Work and Pensions and its unaccountable satellite agencies, he received neither a statement of the original decision nor the promised Mandatory Reconsideration forms. Instead, some time later, when he phoned to enquire about the cause of the delay, he was informed that the Mandatory Reconsideration process was already completed and that the original decision had been upheld.

It would seem that the Department of Work and Pensions has a very fragile grasp of the notion of Natural Justice: quite rightly, a process is in place to allow claimants to challenge the decisions of the HAAS but these appellants are given no opportunity to prepare a case, they are denied access to the evidence on which the original decision was based, they are prevented from submitting any additional evidence that might counter the original decision, and they are given no opportunity to appear before the panel to present their case, either in person or via a representative. Kafka-esque is hardly an adequate description of what is a manifest denial of justice to some of the least privileged members of our society - and the British Government has the audacity to lecture foreign governments on the shortcomings of their human rights provision.

Daniel’s only remaining course was to submit a formal appeal to a benefit tribunal but for this he would have to wait several months. In the meantime, his benefits remain stopped and he will have to survive on so little that he is in danger of starvation, with eviction from his flat a real possibility. “I feel deeply that the whole system has been deliberately designed to frighten people, to make them extremely fearful; the whole system of punitive sanctions is conceived to inculcate fear. I am now so scared of becoming homeless that I may try to return to work even though I know that I’m not up to it yet, that I may make myself ill again, and that I will most likely fail.”

Daniel is only partly right: fear might be the consequence of sanctioning claimants, or depriving them of benefits on specious grounds, but the real intentions behind this inhumane treatment of the disabled, the sick and the vulnerable are much more sinister. Having rescued several ‘casino banks’ with billions of pounds of public money, HM Government has imposed on the nation what appears to be a perpetual state of austerity, ostensibly to repair the budget deficit and to ‘balance the books’ by some future date, a date that keeps on moving forward. However, this austerity offers almost the ideal climate in which to reshape UK society, to ween it off the post-war, ‘cradle to grave’ dependency model and to move it on to something altogether more spartan and neoconservative.

The British Welfare State, perhaps unique in the world, was built up through the twentieth century and massively expanded after World War II, with the introduction of the NHS and a range of other work and social benefits; it has, for generations, provided an invaluable safety net for all those who suffer life’s cruellest misfortunes, who find themselves unemployed, or homeless, or long-term sick, and this safety net is being deliberately and painstakingly dismantled.

In order to achieve the destruction of institutions that are much loved by the populace, society has to be deliberately polarised and fragmented - as we all know, once the masses are divided, they are easier to rule. The endless hunt for those now labelled benefit scroungers, shirkers and the undeserving poor has become a favourite sport for right-wing politicians and journalists, perhaps a sort of substitute for fox hunting. The British gutter press and the other popular media are an essential part of the brainwashing and, sad to say, such is their success that dismantling the Welfare State is now accepted as necessary, even by those who are likely to need it most. We now claim to have almost full employment in Britain but the fact is that government has imposed such draconian measures on the unemployed, that all those who are out of work are forced to accept almost any job they’re offered because those who refuse are immediately sanctioned and lose their benefits, thus being conveniently and immediately removed from the list of the unemployed. In other words, the system is not dysfunctional, it does work, exactly as it was designed to do; it brings down the numbers of the unemployed, it achieves savings, and the scroungers and shirkers are taught a lesson. The real costs of these measures, the impact they have on people’s lives, are never calculated.

Inevitably, once the unemployed had been successfully packed off to earn a pittance on zero-hours contracts, attention turned to those who claimed to be unable to work because of a disability or chronic illness. They were the next in line to receive a neoconservative lesson in self-sufficiency. Of course, most people would accept that there will always be a small proportion of disability claimants who, if they are not actually malingering, are perhaps on the margins of disability and who should therefore be encouraged to take up some economically useful work, but our political masters would seem to have concluded that everyone who claims to have a disability must be a deceiver and that this justifies the use of extreme methods, methods that are punitive, harsh and devoid of humanity. Ken Loach’s fictional film character, Daniel Blake, and our own very real Daniel Lul, whose story this is, have both become victims of a regime that is arbitrary, cruel and inhumane - Daniel Blake’s death is the inevitable consequence of treating vulnerable claimants as if they were criminal recidivists and the statistics that reveal the tragic outcomes for too many claimants are deeply shocking.

While the responsible arm of Government, the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) has set financial targets for savings on welfare payments, it has subcontracted its dirty work; the actual assessments are carried out by private companies. Atos, a French outsourcing company, pulled out of its ‘work capability assessment’ business (a five-year contract worth £500 million) one year early, because it had come under such repeated fire during its tenure. Labour MP, Dennis Skinner, described Atos as a ‘cruel heartless monster’ and perhaps with some justification: PIP claimants won 60% of their appeals against Atos between July and September 2015, with 58% of ESA claimants also winning their appeals. And some of these cases were truly shocking, with some appellants having lost benefit as a result of an Atos assessment when they were suffering from terminal cancer and other life-threatening illnesses.

The DWP has since subcontracted disability assessment to other companies whose reputations are equally tarnished. The hard fact is that if you contract with a private company, set tight targets for the achievement of savings, and offer rewards on the basis of targets met, you cannot be surprised to find that any company operating on these terms will do everything possible to meet its targets and to maximise profit. Humanity has no place in this kind of contract; the client is seen only in terms of revenue, as an opportunity for withholding costly benefits, so however nasty the work, it has to be done. The DWP achieves its savings and those in the upper echelons of Government, who are responsible for putting these systems in place, have kept their hands clean; they can sleep soundly in their comfortable beds.

Some even more telling statistics, grudgingly issued by the DWP, revealed that during the period from December 2011 to February 2014, 2,380 people died within 14 days of being denied their Employment and Support Allowance and declared fit for work by the DWP’s agencies. This is not to say, of course, that these claimants died because their benefit was cut, but what it surely does reveal is that their assessment as being fit to work was utterly and completely wrong - they were not fit, they were dying. Another 7,200 claimants died after they were awarded ESA but were placed in the separate work-related activity group, a category that identifies claimants who are not fit to work but who may be able to return to work in the future so need regular re-assessment - for over seven thousand of these poor souls, their only future was the hereafter. The DWP insists that these statistics should not be misunderstood, and claims that the above figures are not shocking at all.

But one thing is certain: a civilisation or a country may be justly judged by the way it treats the weakest members of society - its young, its old, its infirm and its disabled, its insane, its convicts, and its destitute. What then would such a judgement be of the UK in the Year of Our Lord 2017, ‘Global Britain’, the world’s fifth richest nation, when it exploits the crudest mendacity and the most abject incompetence to determine that terminally ill claimants are fit for work and, as these desperate people stagger towards death, contemptuously robs them of those paltry benefits to which they are absolutely and justly entitled?

Should you ever come across our young man, Daniel Lul, on the street, on a rainy night, in his wheelchair, with his prostheses in a bag next to him, together with his few other worldly goods, you must not stay silent, you must howl in rage at our politicians who have abandoned their moral compass and who have dehumanised our society through their dogmatic promotion of ‘Social Darwinism’, a creed that only allows the fittest to prosper. Daniel’s only crime was to be taken seriously ill with meningitis; having paid his dues for seventeen years, he might have reasonably expected to be given some support during the long period of his recuperation. However, our brave Daniel says: “I have been given a second chance - I am alive!” and he means it; he is strong and determined to get his life back and he could be an example to us all of what the human spirit can achieve in the face of the most extreme adversity. But, if we now pull the rug from under his feet, his amputated feet, it will be an unimaginable cruelty, a crime against humanity that should make every one of us hang our heads in shame.

Interview date: 10th May 2017

Text edited: 26th May 2017

Update (November 2018)

Since the above article was written, Daniel has continued to recover: he now manages to do occasional voluntary work, whenever he feels up to it, and is endeavouring to build back his strength by taking part in various charitable events and initiatives for the disabled. For the extraordinary efforts he has made as a committed volunteer on a local disabled people’s project (LADPP) including the recruitment and training of new volunteers, he was one of two people, in November 2018, to be Highly Commended in the Disabled Champion of the Year Awards.

But that very same month, on 9th November, Daniel had to face another assessment of his eligibility for the Employment and Support Allowance and, at the time of writing, he is living through another nerve-wracking period of waiting, full of stress and uncertainty; what if he should be failed again and lose his living and housing benefits? That would render him homeless once more - a man still recovering from a life-threatening illness, an illness that resulted in the amputation of both his legs, left to the mercy of the street. Is it any wonder that a recent report by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights should condemn the UK government as “punitive, mean-spirited and often callous” in its treatment of the country’s poorest and most vulnerable?

At this moment, for Daniel, the Sword of Damocles still hangs above his head; his future remains perilously uncertain and he fears losing his home, again.