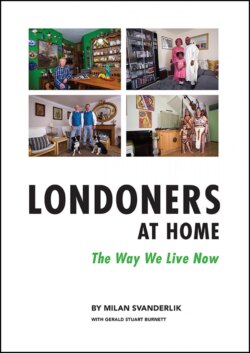

Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? LIVING IN A TENT

ОглавлениеAimée Lê

For Aimée, living under canvas for nearly three years was the only realistic and affordable option while she studied for her PhD. But she was not alone: camping in the shadow of Heathrow Airport, she was a proud member of the Grow Heathrow Intentional Community, a living protest against airport expansion. Not only had she found London rents astonishingly high, in comparison with the USA, but also, when she lived in a flat here, she always had the impression that she could be evicted at any moment. And living in dorms, where there were regular inspections, she felt that there was no privacy. Wherever she’d lived in London, she’d always had the feeling of not quite belonging, a feeling that she couldn’t go outside her own four walls. There was hardly any tranquility to be found in such a busy city, either during the day or even at night. In comparison, living in her tent was calm and quiet; her tent was her own private space; you were never disturbed; you could even hang your washing out in the open air to dry; and, if need be, you could always role up the tent and just move on. In her tent, Aimée found that she could think and write in peace.

Photograph: Aimée Lê at home, by her tent, in the shadows of Heathrow Airport. (Photography: 21st April 2017)

The full story:

One thing that keeps coming up in the stories associated with this project is the astronomical cost of housing. London is still a powerful magnet to many people, most of whom relocate to the capital in search of work - this trend has been long established. Yet never before has there been such an acute shortage of affordable accommodation. Even a graduate with a good degree, in one of the better-paid professions, will discover to his or her perturbation that the cost of renting in London can easily devour more than 60% of take-home pay. London has become one of the world’s most expensive cities to live in and it is therefore hardly surprising that numbers of single people, and occasionally families too, have been obliged to resort to what would, but a few years ago, have been seen as extreme measures for anyone in paid employment. Young people are now living under canvas on campsites around the periphery of London, or on the patches of undeveloped, post-industrial no-man’s-land that are dotted around this vast city of ours.

Not so long ago, campsites were mainly places where you would find teenage tourists or young students staying, at minimum expense, while exploring the city ‘on the cheap’. But not any more: large sections of these sites are now reserved for the growing numbers of so-called, ‘long-termers’ who see a tent as their home. Even here, the happy campers can expect to pay as much as £20 a week for a one person pitch - mind you, that does include services like showers and lavatories, essential if you are to turn up at work in a presentable state. Regular bus services operate from these campsites, ferrying the young commuters to and from their places of work.

To explore this topic, and to find out at first hand how it feels to make your home under canvas, I headed back to an established ‘Intentional Community’ that calls itself, Grow Heathrow; it is located in the centre of the little village of Sipson, one of the communities threatened with extirpation by the expansion of the UK’s busiest airport. The community is a group of 50 or so people who have primarily taken up residence there to oppose and obstruct the building of Heathrow’s proposed Third Runway. But the community also aims to demonstrate, by example, that carbon-neutral living in a large city is possible; they believe that it is high time to take action against our present way of life and the endless consumption that is bringing us closer and closer to environmental catastrophe.

Soon after my arrival, Luke, the community’s spokesperson that day, introduced me to a smartly dressed young woman, clutching a collection of books, a laptop and a small rucksack; she is Aimée Lê. Luke introduced her as “our resident poet and perhaps the only person who wrote a PhD thesis while at Grow Heathrow.” Having just returned from working at the university where she teaches, Aimée agreed to take me to see her tent, located under a tree, in a secluded spot at the very perimeter of the Grow Heathrow community. Her home seemed surprisingly small but the neat little tent, pitched off the ground on two wooden pallets, was surrounded by flowering plants. Though it lay under the shade of a large tree, it faced a brightly-lit, blossom-filled meadow where nature had been allowed to go about her business unhindered, despite the fact that the bustling Heathrow terminals were not that far away. The place was wonderfully peaceful and, somewhat surprisingly, rather than the noise of jet aircraft, mostly what one could hear was birdsong. “I came here in January 2016,” says Aimée, “and this little tent has been my home since then.”

Aimée continued her story: “I was born in Michigan, in the USA, but my dad came from Vietnam. Though my mother did come from Michigan herself, her mother was born in East Prussia and was originally German-speaking. So, while I certainly see myself as an American, I am very aware of my own international ethnic roots, of the fact that my parents’ views were always the views of outsiders, and that they were perceived as outsiders themselves by other people.”

As I spoke to Aimée, an artist and poet, I soon found it becoming clear that she was much more than that; she was evidently a person with very well-developed and strongly-held political views, someone with a comprehensive understanding of the world around her and how it works.

I asked about the kind of childhood she had had; laughing, she replied : “You could say that I grew up in the shadow of the University of Michigan and that was pretty influential, I guess. I was mostly surrounded by people who were not only better educated than my parents but also more affluent. Though my mother worked for the local courthouse, and my father worked in computer programming, they both had distinctly left-wing political leanings - this seems rarely to be the case with recent immigrants into the USA, especially amongst those from Vietnam.”

“Inevitably, growing up in the company of all those academics had a profound effect on me. I went to Dartmouth College, an east coast ‘Ivy League’ establishment, where most of the students had wealthy, well-connected backgrounds; they were a bit out of my class. Nevertheless, I graduated with a BA Honours degree in English. Given my family background, I was a politically aware person from early on and when, in 2011, the financial crisis really began to hit home in the USA, I got together with a number of other left-leaning students and set up the Occupy Dartmouth initiative. While this was a local protest movement, it echoed the aspirations of the Occupy movement elsewhere. We offered general advocacy for students and workers and did our best to encourage people to engage in a different type of political discourse.”

During 2011, Aimée toured the US with Fiona Chamness, promoting a new poetry collection, Feral Citizens; the collection was published by the Red Beard Press and Aimée was listed as one of Muzzle magazine’s ’30 Writers Under 30’.

“I have been in the UK since 2013, so for almost four years now. I study and work at Royal Holloway, University of London, and I’m about to complete my PhD, but I also teach poetry there, as well as literary criticism, and I do an introduction to English poetry course.”

In view of these elevated academic pursuits, I asked Aimée how she had ended up living in a tent in the proposed path of the Third Runway. “I had some experience of living under canvas during my time with Occupy Dartmouth, but the tents we had there were much larger structures altogether. Having arrived to London, I shared a flat initially but I found the experience very depressing. University accommodation is hard to get and just at the worst possible moment, my lecturing time was reduced, so I just couldn’t figure out how to make enough money to pay my rent. London rents are astonishingly high in comparison with those I’ve been used to in the US. So, I simply decided to reduce the number of my possessions and join the Grow Heathrow community. Of course, my own political perspective broadly chimes with those of the people who live here, and now I’ve learned about and embraced the environmental aspects of the community too.”

Aimée talks about what she sees as some of the real advantages of living in a tent: “I got really depressed when I was living in London; I developed a feeling that I couldn’t go outside my own four walls, that I couldn’t enjoy any tranquility - it is such a busy city, both during the day and at night too. Living here is so quiet in comparison; you can even hang your washing out in the air to dry. When I was living in a flat, I always felt that I could be evicted at any moment, and when I lived in the dorms, there were regular inspections and I felt I had no privacy; I always had the feeling that this was not ‘my place’. By contrast, my tent is my own space. I feel I can always role it up and move on, if need be.”

“At the beginning, it sometimes felt a bit scary, but I have grown to like it. I now see it as something I could easily do in the future, if I had to. Because I am in my own little private area, I am never disturbed; I can think and write in peace. But because I also live in a community, I never need to feel lonely - there are always others nearby, we meet in the common spaces, we share food, we share ideas, and we make the place work by sharing the responsibilities together. One lives in a community with people yet it is still possible to have privacy here. Most importantly, I really feel that I belong to something worthwhile.”

“The major disadvantage of living in a small tent is simply the lack of storage. I’ve now learned to live with only a few possessions and I understand much better that most of the things that I used to haul around everywhere were pure ballast. Mind you, I do occasionally have to ask others, the ones who live in wooden huts, to store my books for me, and some of my clothes as well. My tent is rather small! In the past, I used to find it difficult to build deeper relationships with people, but that’s what I feel can do now. Generally speaking, living here has been a positive learning experience, and over this recent period, I have not once thought of moving anywhere else; this is probably the best indicator that I am truly happy here. If someone were to offer me a nice flat in London tomorrow, at £100 a month, I’d probably turn it down. Here, it’s so much easier to find some private space, unlike if I were living in a flat-share. In the chilly outside world, it is much harder to find a community where one can be happy and sociable but also be oneself.”

Aimée has been writing, reciting, teaching and publishing poetry for some time now, so I asked her where she might see herself in five or ten years’ time. “I am politically active and I hope to finish the large body of work I am engaged on at this moment. I am 26 and hope to travel more, to teach, to learn more, and to get even more engaged in political and environmental causes. In the US, I have been mostly involved with movements that strive to resist the ever-increasing power of the big corporations, and the unscrupulous, uncontrolled behaviour of the financial sector that every day enriches the top 1% at the expense of the majority. Having come here, I now understand far better the damaging effects of this global concentration of wealth and how this larceny connects with the promotion of rampant consumerism and the exploitation of those who have lost even what little power they had.”

“We face formidable opposition but I also have the feeling that the number of people who are starting to resist is on the rise too. I can now see quite clearly how the selfsame struggle connects these protest movements around the globe and I believe that I must continue to be part of it. Climate change is something that we cannot afford to close our eyes to and never-ending growth is definitely not the answer; it is simply unsustainable.” Coming out and saying this is still regarded almost as heresy, even within some universities where iconoclasm ought to be applauded and new ideas encouraged to bloom.

Having lived for three years under canvas, Aimée will soon be moving into something much more solid; no, it’s not bricks and mortar but her very own wooden hut - it will even have its own heating stove. The space will be larger and she can have her books around her, without the risk of getting them damp; but, she says: “I will always think fondly of living in my little tent; it was cosy and every time I’d been away, it welcomed me back, it protected me.”

Interview date: 21st April 2017

Text edited: 17th May 2017