Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? LIVING IN A HUT

ОглавлениеAli Tamlit

Partly out of choice, Ali lives modestly, close to Heathrow Airport, where he actively campaigns against the forces that seem content, in their never-ending pursuit of corporate profit, to poison the air we breathe and gradually to destroy the planet that is home to all of us. Following his graduation, though Ali had no ‘grand design’ for his career, he was already harbouring a strong desire to find some way of putting into practice those ideas that he believed could both influence change for the better, and impede the trends that he saw as socially divisive and environmentally destructive. He felt, and still feels, that direct action, peaceful protest and indefatigable campaigning are amongst the few effective ways to stop, before it is too late, the juggernaut of corporate coercion and greed that is currently ravaging the globe. It is his belief that every one of us, the whole of responsible humanity, must resist these pernicious forces and save the planet, before it is too late. He would certainly endorse one of the latest slogans of the environmentalists: “There is no Planet B”.

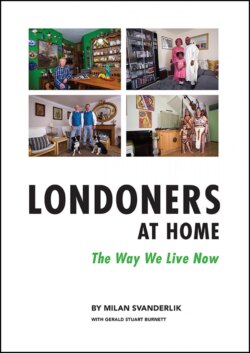

Photograph: Ali Tamlit in his temporary home, a hut at Grow Heathrow, an Intentional Community. (Photography: 21st April 2017)

The full story:

Ali Tamlit is the young man I met outside the wooden hut that he calls home; it stands underneath the remains of a large greenhouse. This is where fruit and vegetables were grown in what was once, many years ago, a large nursery. Ali’s hut is clearly a DIY effort but I am told that the previous resident, who designed and assembled it, was a budding architect, and it certainly does manifest certain characteristics that attest to his formal training. Ali tries to live in a carbon-neutral way within the compound of a well-established ‘Intentional Community’ that calls itself, Grow Heathrow.

The community has been located here for over seven years, right in the centre of the little village of Sipson - unlike the nearby villages of Harmondsworth and Longford, which will be completely razed to the ground, Sipson will only be partly demolished if the Airport’s current plans for expansion get the final go-ahead. The Grow Heathrow community comprises fifty or so people; it is largely ‘off-grid’ and as self-sufficient as possible, given its suburban location and the constraints of the site. Members of the community generate their own electricity, grow some of their own vegetables during the Summer months, and strive to live a carbon-neutral existence. Of course, they are also there to protest; together with the remaining local residents of the three doomed villages, they oppose the further expansion of Heathrow on purely environmental grounds.

After only a brief exchange with Ali, it was clear to me that he is deeply involved with the community and some would certainly see him as an environmental ‘activist’. Once the photography was completed, I asked Ali to tell me something about himself and what had brought him to this place; he replied: “Though I was born in Wales, I grew up in Yorkshire, in the countryside around Harrogate. I was raised on a smallholding, for my mum was into farming; she kept chickens, goats and pigs. All in all, it was a good place to be a child. You could say that my mother was a bit of a hippy and she certainly held strong and well-informed opinions about the environment; she also inculcated in me, from my early childhood, the fundamental ideas of fair trade and social justice, giving me an awareness of the consequences of inequality, both within our own society and worldwide. Those who live close to the earth, and who live from its produce, can often discern, instinctively, what is good for the natural world and what can lead to its destruction.”

Given that his parents clearly hailed from elsewhere, I asked Ali how well he and his family had been received within a small Yorkshire community. “I didn’t notice any difficulties in my early years, but as soon I went to school, I experienced racism; I was bullied there for the simple reason that I was different. Because of it, my mother decided to take me out of school and to give me home tuition up to the age of eleven. My father had grown up in Trinidad but was ethnically Chinese, so from the very beginning of my state education, I was exposed to blatant racism.”

“Aged eleven, I returned to state education and attended the local secondary school, going on from there to Manchester University, where I studied Geography. That was the place where I began to form my views and deepen my understanding, not only with regard to the physical condition of the world and its various systems, but also in relation to the way human beings can, and often do, shape life on this planet of ours. I started to comprehend the significance of what nowadays we broadly term ‘climate change’, and I began to understand the historical, political and scientific perspectives associated with that change. There were a number of Marxist lecturers at the University and they were happy to offer alternatives to the orthodox teaching of Economics; they helped me to understand how capitalism really works and how it has come to define virtually all the major economies in the world. Armed with all this knowledge, it was perhaps unsurprising that I became more political too. I graduated when I was 22 and while I didn’t have a ‘grand plan’ for my career, I already harboured a strong desire to find some way of putting into practice those ideas that I believed could both influence change for the better, and impede the trends that I saw as socially divisive and environmentally destructive.”

Ali continued: “I decided to study for a Master’s degree in International Development and, being an EU citizen, I was able to do this in Sweden without the need to pay exorbitant tuition fees (Sweden provides higher education free to all of its citizens and thus to other EU citizens too). This course had been specifically designed to train the new generations of NGO (Non-Governmental Organisations) practitioners, to prepare them for going out into the developing world to do fieldwork and to help with a range of pressing environmental and socio-economic problems. Alas, within a matter of weeks, I realised that I had set off on what was for me the wrong path; I also came to the conclusion that the course was pretty terrible too. Nothing is ever wasted, of course, and at least I came to a clear understanding of why I didn’t want to do the sorts of things that we were being coached for.”

“There will always be notable (perhaps even ‘noble’) exceptions, of course, and while there are NGOs that certainly undertake worthwhile, first-rate work, it was my perception that, basically, we were just being trained in the best ways of dabbling at the margins, promoting developments that were essentially no more than extensions of free market capitalism. It struck me that NGOs mostly go to the places where the funding bodies want them to go, places where, in too many instances, they ignore or ride roughshod over the wishes of the local people, the very people they were supposedly sent to assist. In the long run, these kinds of interventions quite often make things worse. It also became clear to me that the resources invested in various NGO initiatives, even when the figures looked impressively large, were really peanuts; in comparison with the vast sums of money that international corporations were pouring into destructive development, the NGOs’ resources were chickenfeed, completely inadequate for addressing the problems that were often created by the corporations in the first place. I didn’t want to have anything at all to do with this; I wanted no part in it whatsoever.”

“Though I completed the course, I decided against going to those parts of the world where NGOs tend to operate; instead, I stayed here in the UK, a country that I consider to be one of the major contributors to the ills of the world, both historically and currently - I see living and working in Britain as being, so to speak, in ‘the belly of the beast’ and this is where my work must begin.”

Ali is amongst those who are fiercely opposed to the expansion of Heathrow Airport which, with regard to air quality, has already rendered its environs amongst the most polluted areas in Europe. He passionately believes that the UK’s existing airport capacity is sufficient to meet the genuine needs of commerce; that a number of perfectly well-located airports are chronically underused; and that only corporate greed, political dogma and a lack of creative thinking prevent us from utilising a great deal of unused capacity.

As a true activist, Ali has no hesitation in taking direct action: in June 2015, he joined a group of fellow activists from Plane Stupid to make a peaceful protest against Airport expansion; they cut through Heathrow’s perimeter fences and locked themselves on to the runway, thus stopping all air traffic for six hours. For this, they were arrested, charged and brought before the Magistrates at Willesden; initially, they faced prison sentences, though these were later commuted to suspended sentences. In an essay published in ROAR Magazine, Ali wrote:

“Our occupation lasted over six hours and resulted in the cancellation of 25 flights saving hundreds of tonnes of CO² from being emitted that day. All thirteen of us were eventually removed, arrested and charged with aggravated trespass and unauthorised entry to a restricted aerodrome.

During our trial we used a so-called “necessity defence”, arguing that our actions were necessary to prevent death and serious harm. We showed that this was being caused both by the effects of climate change around the world and by the local pollution, particularly nitrous oxides, which have been found to be responsible for 31 premature deaths a year within twenty miles of the airport. While Judge Wright admitted that a clear link exists between aviation and climate change, she found us all guilty and told us to “expect jail” at our sentencing on February 24. If we do serve a custodial sentence, we will be the first climate activists ever to go to prison in the UK.”

This highly publicised campaign, together with a number of others staged around the country, did yield some results: in a pre-election pledge, David Cameron famously stated that there would be no Third Runway at Heathrow, “no ifs, no buts”, and the Coalition Government duly dropped all expansion plans. But of course, that wasn’t the end of it; in July 2015, after years of investigation, scrutiny and analysis, the (so-called) Independent Airport Commission recommended the expansion of Heathrow - suffice it to say, no-one was surprised. So, the battle is on once more. It would be truly amazing if an incoming Conservative Government, with a bigger majority and an almost manic drive to transform the UK into ‘Global Britain’, chose not to force through the Third Runway plans, making 2017 a shameful year to remember.

I asked Ali what it felt like to live in a wooden shack, amongst the Grow Heathrow community. Responding without hesitation, he replied: “I live modestly, I have few possessions and therefore I don’t need much space. Though the hut is constructed so it is above the ground, on a wooden platform, it isn’t rat-proof! The rats are a real nuisance; they manage to get everywhere and into everything; they really are, I suppose they always have been, nature’s perfect entrepreneurs, the ultimate opportunists. In a commune like this, there is the benefit of living in proximity to others yet having one’s privacy too. Of course, here at Grow Heathrow there is a real mixture of residents and they have a whole range of motivations for being here. There are umpteen different cultural and political backgrounds and sometimes this can lead to disagreement and disgruntlement when decisions are made collectively. But there is one huge advantage, and that is that everyone’s views get challenged; this probably wouldn’t happen if you lived in an ‘idealogical bubble’, just with people whose views were identical to your own. Here, even though we’re all very different people, we strive to cooperate, to work together, and to engage in collective decision-making - you can genuinely feel that you’re making a difference. How often could this be said of people who work in large corporations, where everyone is no more than another cog in the wheel, and where unorthodox suggestions or ideas are rarely welcomed, mostly ignored. I feel that by being here, through taking part in other activist groups, by speaking, lecturing and writing, I am making a real difference.”

In response to my question about how Ali saw his own future mapped out before him, he replied: “I will strive to continue my involvement in political and environmental activism. To me, being engaged is the most important thing; I will strive to get others engaged and I will carry on doing this for as long as I can. Being passive is not an option for me: a juggernaut of corporate coercion and greed is currently steamrolling around the globe and it needs to be stopped before it is too late. Humanity must resist and we must fight on.”

A recently-published report estimates that every year, in the UK, over 23,000 premature deaths are caused by Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) alone. Our own government had to be forced, by a CleanEarth court action, to publish its plans for tackling the UK’s toxic air crisis and yet, when the document was eventually released, it contained few concrete proposals for mitigation, largely shifting the burden of responsibility on to cash-strapped local authorities who have little power to effect change. When nothing happens, they will be left to take all the blame and it is they who will have to face the ire of their electorates when, in fact, it is central government that takes all the questionable decisions, overrides local authorities and local people on major planning issues (like fracking) and seems indeed to represent no constituency other than the interests of a few super-rich individuals and overbearing corporations, who already exercise extensive control over the world around us. As Caroline Lucas, Co-Leader of the Green Party, said recently of this long-awaited plan: “The government is standing idly by while Britain chokes. This feeble plan won’t go anywhere near far enough in tackling this public health emergency.”

Ali’s struggle will doubtless go on, for he and his companions are pursuing the struggle on behalf of us all. If we allow them to fail, or see them crushed, it will be at our own peril - we might be able to fly more frequently, or take even more cheap weekend city breaks, but in so doing we will be helping the children of West London to choke. If we go on like this, in the end, it may only be Heathrow’s rats that can survive. Perhaps they will prove to be the only future occupants of Ali’s hut, a little dwelling currently lodged in an oasis of hope under the flight paths. Grow Heathrow is certainly a place we can lean from.

Interview date: 21st April 2017

Text edited: 15th May 2017

Update (February 2019)

Ali Tamlit was one of the Stansted 15 who obstructed the take-off of a Boeing 767, chartered by the Home Office to repatriate people to Africa - a number of those due to fly either had pending appeals or had the right to remain in the UK. It was a peaceful political protest, to which the state made a disproportionate response: initially charged with ‘Aggravated Trespass’, all 15 were subsequently charged under the Aviation and Maritime Security Act, 1990, passed following the Lockerbie bombing and aimed at aviation-related terrorism. In January 2019, they were all found guilty; two received suspended jail sentences and twelve were given Community Orders. Having a previous conviction for aggravated trespass, Ali was sentenced to nine months in prison, suspended for 18 months, plus 250 hours of unpaid community work. The convicted are now appealing, in which endeavour they are being supported by a number of human rights organisations.

Though their action was clearly a peaceful protest, it attracted a great deal of hostile publicity and demonstrated yet again how the apparatus of the state can sometimes react in a manner that is not commensurate with the crime committed. It would seem that while Britain likes to preach to the world about the need for political freedom and the right to peaceful protest, it is willing, at home, to resort to increasingly draconian measures against those who dare to make public protest against government policy.