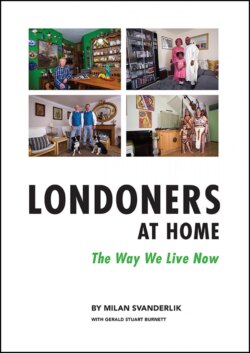

Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? SLEEPING ON THE STREETS

ОглавлениеBuuhan

For a young man called Buuhan, the streets of London are home, just like hundreds of others in the capital who are forced to sleep rough. Over the five years to 2018, the number of rough sleepers in Britain has doubled. Official estimates suggest that 3,600 people sleep on the nation’s streets every night but these statistics are disputed by the homelessness charities who actually work in the field and who see this figure as a significant underestimate. One thing is certain, however: a society can always be judged by the way it treats its weakest members: its young, its old, its infirm, its insane, its convicts, and its destitute. So what judgement would be passed on ’Global Britain’, in the Year of Our Lord 2018, the fifth richest nation in the world, when we consider the plight of those whom we have quite consciously abandoned to pass miserable lives on the streets of our greatest and wealthiest cities?

Photograph: Buhhan under a railway arch at Waterloo (Photography: 4th April 2017)

The full story:

I have now lived in London for over 45 years and there have always been rough sleepers amongst us here in the capital. Rough sleepers are found in most of our major conurbations and you might say that they are different manifestations of society’s underbelly. Amongst those found sleeping on our streets are people who may have chosen to opt out; people who have fallen through the holes in the social safety net; people who may have spent part of their lives in prison, in the services, or in some kind of mental institution; refugees, illegal immigrants and those who are on the run from unbearable domestic relationships, or from the demons inside their own heads; people who have gambled and lost; and people whose grip on reality has been fractured through alcohol or substance abuse, who sought nirvana but ended up in a nightmare on our freezing, wet streets.

Also amongst those on the streets are the simply homeless, those who just cannot afford to pay for a bed for the night, or a roof over their heads. During the last few years, I have seen the situation in London deteriorate markedly: now there is hardly an underpass, a bus shelter, or a shop doorway that, late at night, is not populated by rough sleepers, trying to keep warm in their sleeping bags or in a nest of newspapers and cardboard boxes. Some prefer to sleep in the warmth of night buses, travelling aimlessly through the darkened streets, to-ing and fro-ing from one bus terminal to another.

Rough sleepers are certainly an integral part of London’s streetscape and though I was determined to include them in Londoners at Home: The Way We Live Now, I understood how difficult a task it would be to find a suitable, willing subject. By sheer coincidence, pure serendipity, my attention was drawn one day to an obvious assemblage of objects under one of the railway arches near Waterloo Station, close to my gym. There was a sleeping bag, neatly rolled up, two pillows, a discarded but once very expensive office swivel chair, and a sweet collection of quite clean-looking stuffed toys, including a big-eyed white cat, a Captain Hook, and a rather jolly Mickey Mouse. As it was still daylight, the owner of these possessions, and resident of this patch of sheltered pavement, was not there; however, I took my chance and returning later on that evening, with my camera, I found a young man already tucked up inside his sleeping bag, but still reading his free newspaper.

As I approached, I could see from his his eyes that he was thinking, “What the hell does HE want?” But I took plenty of time to explain about the project and, at the end of my little presentation, asked him if he might be willing to be part of it himself. “I love art too,” he said, “so yes, I wouldn’t mind being photographed.” It was a chilly Spring night, it was starting to drizzle, and the railway arch seemed a great deal more like a wind tunnel than a shelter from the elements, but I did manage to take some photographs of this sad young chap. He even volunteered to tell me, a complete stranger, a few things about himself; of course, I listened: “My name is Buuhan and I came to London from Portsmouth. I am a theoretical physicist but things went wrong in my family and I had to leave home. But the hope of finding housing there was zero, because I don’t belong to any of the minorities who are entitled to be housed by the Council. So I came to London, where at least there are day centres where I can get some warm food and keep myself clean. I’ve been sleeping on the streets for six months now.”

Alas, at the very moment when I was getting some useful background information, another rough sleeper sat down close to us and started to construct a night shelter for himself out of a large cardboard box. He looked at me and my camera, then towards Buuhan and muttered: “See mate, fame at last! You’ll be eating at the Ritz next.” I felt that, out of respect for Buuhan’s privacy, I could not very well continue the interview any further. But I planned to return the following night and so we parted, with me heading off to my warm, comfy bed in Chiswick, leaving him in his sleeping bag, under a damp and windy archway, keeping close to his collection of fluffy toys and the inexplicable, sleek, high-tech office chair that looked, against the ancient, dirty, bare brick walls of the railway arch, more like an alien sculpture than a piece of office furniture.

I returned during the evening of the next day; he wasn’t there, so I left a note. I returned two days later and though his possessions looked as though someone had been rifling through them, my note was still there, untouched and presumably unread - Buuhan couldn’t have seen it. He would seem not to have returned to his patch for the two days since we had spoken, leaving his fluffy friends looking abandoned and forlorn.

Some of our politicians claim repeatedly that the UK is the fifth richest nation in the entire world but behind all our prosperity, behind the unimaginable wealth of the richest few, there is a deep-seated cruelty and contempt for others that should shame every one of us. We somehow imagine, or perhaps we convince ourselves, that poverty and homelessness only happen to the feckless and the irresponsible, but how wrong this is. The post-war settlement built nobly on a pre-existing, rudimentary welfare system, recognising that if everyone made small, regular contributions to a ‘national insurance’ fund, resources would be amassed that could provide a real safety-net for anyone who was hit by accident or misfortune, lost a job or a home, became ill, or faced a rough patch in their lives and needed temporary support or an affordable dwelling - basically, the help people sometimes need to rebuild their lives.

But the tide has now turned against such ‘socialist’ or ‘collectivist’ ideals (though nobody at all seems to find fault with ‘private’ insurance) and every individual must fend for him or herself. Those who fall by the wayside in this fierce competition for life’s material blessings are seen to be at fault and are thus labelled as ‘undeserving’. We are told that the Welfare State only creates dependency, turning workers into scroungers that the country can no longer afford. Harking back to Victorian times, we have again become a country that Dickens would recognise, a cruel nation that adheres to the dogma that the strong should be allowed to prosper without constraint, while the weak must pull their socks up and tighten their belts, or else go to the wall; they should not expect other hardworking folk to support them. The full-scale dismantling of the Welfare State, largely created by the post-war Labour Government, is now in full swing and all around us the harsh climate of seemingly perpetual austerity provides an ideal environment for turning this savage dogma into practice.

This is not to say, of course, that there were no rough sleepers on London streets during the period when the Welfare State was still fully functioning. There will always be people whose choice it is to opt out of society, those who suffer some degree of mental illness but who are not ill enough to be hospitalised, individuals who, through drink or drugs, are on a destructive personal trajectory, or those who have in some way or another gambled with life and lost everything.

Some of these rough sleepers will need to be helped by one of the leading charitable organisations in the field (like The Connection at St Martin-in-the-Fields, The Passage, Thames Reach, and St Mungo’s) who do their best to give them decent meals, help them to keep themselves clean and well-groomed, and try to assist them to find a permanent home, to get back into work, and thus achieve a more stable life.

Over the past five years, the number of rough sleepers in Britain has doubled. It is officially estimated that 3,600 people sleep on the nation’s streets nightly but these statistics are disputed by the homelessness charities who are working in the field and who see this figure as a significant underestimate. Most London shopping streets have people bedding down in doorways, or by air-conditioning vents, and the better-lit underpasses are generously populated with the homeless every night.

No-one will forget the memorable statement of a former Tory minister, who described the homeless as, “what you step over when you come out of the opera.” Such jocularity might seem cruel or heartless but it probably contains a germ of truth, insofar as the spacious entrances, porticos, awnings and covered colonnades of our numerous West-End theatres provide good shelter at night time for the legion of sleeping baggers. The situation in the capital is now so desperate that people have actually resorted to sleeping in council recycling bins.

The principal causes of this rising trend in the numbers of rough sleepers appear to be rising rents, savage cuts in Housing Benefit, and the ever-diminishing services provided by local authorities, whose budgets have been cut by around 40% in the long period of austerity since 2010. One contributing factor, especially in London, has been the marked rise in immigration from Eastern Europe. Many of such migrants are highly skilled and have no difficulty finding work, often in London’s booming construction sector, but others, those who lack trades and who may have been already on the margins at home, come to Britain in the hope of getting a decent job (or perhaps just a job) and thus making a better life for themselves.

Sadly, not all such migrants do find work and even amongst those who do will be those who are paid so little that they cannot sustain a decent existence in one of the world’s costliest cities; they will remain desperately poor and be forced to live on the margins here too. All the talk of the tabloids, that these people are only here to milk our (supposedly) generous welfare benefits, is not sustained by the facts: these migrant workers are not entitled to any benefits.

In London, it is estimated that, at one stage, almost half of rough sleepers were from Eastern Europe. These people face additional major problems: while the homeless charities can feed them during the day, contrary to popular belief, they are not entitled to and do not receive any state support, nor do they qualify for hostel accommodation. They cannot even access sufficient funds to pay for their journey home. A number of rough sleepers are also refugees and failed asylum seekers; these sad individuals are trapped in a no man’s land, hiding from the authorities and terrified even to seek medical attention when they need it, for fear of being arrested and forcibly deported.

Sleeping on the streets has never been safe and it can often be frightening, with rough sleepers suffering the theft of their scanty possessions, attacks from fellow rough sleepers, often over ‘territorial disputes’, and the casual violence meted out by drunks and delinquents. Every year, a number of people sleeping rough in London are murdered. Those who have nothing, and who have nothing to lose, will often steal from others who sleep rough but who might seem, perhaps through successful begging or busking, to have more than they do. And rough sleepers are often attacked gratuitously by passers by; they are insulted and abused for their predicament, told they are idle and worthless, bottles and other refuse are thrown at them, their precious sleeping bags are set on fire, and some have actually been kicked to death - they are lucky if they only get spat at or urinated on. Some authorities have been known to round up the rough sleepers in their areas and relocate them outside London, making them someone else’s problem, at least for a while.

Ironically, a proportion of rough sleepers are actually in work, though they are only just surviving. Some pick up casual work from builders looking for a cheap day’s labour, no question asked, in exchange for which they get enough cash to pay for the day’s food but nothing else, certainly not for accommodation. There was a case of two rough sleepers who worked for an agency that sold street cleaning services to local authorities: they were paid so little that the only way they got by was to return at night to sleep on the streets that they’d cleaned earlier in the day - one motive for doing a good job, perhaps? And who is going to offer a respectable job to someone ‘of no fixed abode’? Well, we can all guess who: those individuals, companies and agencies who thrive on the exploitation of an expanding urban underclass, of those who have no rights and no representation, who are willing to work for a pittance and who are seen as a disposable ‘human resource’. And through our obsession with cost-cutting, saving, and protecting the taxpayers’ purse we, as a society, connive at this exploitation, this degradation of the desperate.

When I return once more to the railway arch where Buuhan had seemed so well ensconced but a few days before, his few remaining possessions are all in a heap, his fluffy toys abandoned; soon, the council’s street cleaners will clear even this away, making space for the next al fresco resident of this windy archway - another cardboard box to shelter another broken human being. I cannot help but wonder: “Was this young man who allowed me to photograph him really called ‘Buuhan’? Was he really a physicist? And did I, as a total stranger, have any right to ask him anyway? Any right to expect him to reveal more about himself?” Every day since taking his picture, I have wondered what happened to him, if he is ill or has been harmed, if he has disappeared for some personal reason, and will anyone notice anyway? Now only the photograph remains of that rainy, windy night when he gazed at me observing him through my viewfinder - two totally disparate lives, that have touched at a single point.

We all pass dozens of vagrants every time we’re out and about in central London, the homeless, mostly jobless people who line our streets, though our eyes rarely meet with theirs; we look away, giving ourselves a measure of protection from the pain of seeing what would become unbearable. Even when we give, we mostly don’t look; we avert our eyes from the eyes of the miserable because to look them in the face is an embarrassment, an indictment of our own affluence, our well-fed warmth and comfort, it is simply too distressing. How did we allow this to happen? How do we permit it to go on happening? Even those who have spent much of their working lives in the noble organisations and charities that help rough sleepers to survive, perhaps even to return to mainstream society, now talk pessimistically about the future, almost as if all of their work had been in vain and the fight for a more equal society lost. But there is one thing absolutely certain: a civilisation or a country may be justly judged by the way it treats the weakest members of society - its young, its old, its infirm, its insane, its convicts, and its destitute. What then would such a judgement be of the United Kingdom in the Year of Our Lord 2017, ‘Global Britain’, the world’s fifth richest nation, when we envision the plight of those whom we have abandoned to pass miserable lives on the streets of our greatest, our richest cities?

Interview date: 4th April 2017

Text edited: 20th April 2017