Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHERE do we live? NO-ONE AT HOME

ОглавлениеAbsent Overseas Owners

In some parts of London, around four in every ten properties are owned as investments by companies based in tax havens. Most remain dark and empty for years on end while ordinary, decent, hardworking, tax-paying Londoners struggle to find anywhere affordable to live. A 2016 Commons Briefing Paper indicates that 49% of prime London sales worth over £1m were to foreign nationals. More up-to-date statistics suggest that nearly 60% of the new housing created in inner London is marketed and sold off-plan in the Middle East and in East Asia. So there we have it: every day we can admire London’s ever more dramatic skyline - impressive towers reaching into the clouds - yet many of these glass palaces will never be more than outlines in the sky. They are merely architectural piggy banks for the super-wealthy whose names we are often not even allowed to know. Mind you, why should we need to? Most of us will never know the name of the young man in Brixton who lives in a garage at £100 per week. Some would call this the natural order of things; some might call it ‘Social Darwinism’; I prefer to use a plain English word, it is just the way of ‘the MARKET’.

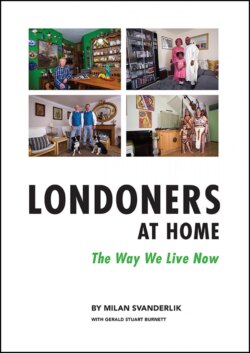

Photograph: A show-flat, one of thousands, routinely marketed to wealthy overseas customers. (Photography: 17th April 2017)

The full story:

One Sunday morning in the Spring, I found myself chatting to an impeccably-dressed, young sales agent, close to the smart reception desk of one of the many new glass and steel tower blocks that now reach high into the sky along the banks of the Thames. The building was still under construction but most of the flats were already sold. I was personally escorted to see a two-bedroom apartment with only a side view of the river (all the premier, river-facing flats had already been snapped up) although this unforgivable shortcoming was reflected in its relatively modest price - it was one of a few under five million pounds. The show flat was lavishly furnished and the careful attention to every detail was truly impressive, but the view was indeed somewhat impaired by the less than appealing facades of adjacent office blocks.

“I fully understand your concerns about what is not such a perfect view,” said the charming agent, very politely. “The flats on the front elevation, with the full river view, were sold by our overseas offices within minutes of being released. However, we do still have one remaining, a four-bedroom apartment on the 40th floor, and that has an unobstructed, panoramic view of the river and the City. That one will sell for around £36 million but it is, of course, rather more than a flat, more than just somewhere to live; it should be seen primarily as an investment.” The charming agent smiled her impeccably fabricated smile, the sort of faintly menacing smile of someone who knows that she has completely wasted her time.

To own a home of such distinction will set you back in excess of £20,000 per year in service charges and, should you want to park your Rolls in the secure underground car park, that will be another £100,000 per annum, thank you. Flats in the palatial, new tower I was visiting are by no means the most expensive London has to offer: in 2014, at the One Hyde Park development in Knightsbridge, a flat was reportedly sold for £140 million, and that was just for the shell - internal walls were yet to be created and all the essential services installed. Three years on, and the same flat has reputedly been valued at almost twice that sum.

Three days after my brief flirtation with luxury living, high in the sky, I emerged from Brixton Underground Station to be met by someone equally well turned out, though not this time an estate agent; this was a young man who had kindly agreed to let me photograph him at his somewhat more modest home. He led the way and soon we entered a secluded courtyard. He unlocked, then pulled up the metal shutters, opened a door, and invited me in to see his home - no glass palace this, high in the sky, but a lock-up garage. There were no windows and no running water either; the temporary cable that had brought electricity into the otherwise dark interior was now disconnected. The rent for this luxury home was £100 a week.

People may wonder why I should cover this particular topic, given that the essential purpose of this project is to reveal and to celebrate the diversity of London life, a purpose that will inevitably involve unveiling at least some of the huge variety of the ways people live. Of course, some people do live in complete luxury while others are obliged to live on the streets, with no home at all, but it was ever thus. Ironically, I discerned one similarity between the garage where our young man in Brixton resides and a great many of London’s newest luxury homes: they are all dark! Our young man frequently has to live in darkness because his garage has no windows and he is often without electricity, while hundreds of luxury flats remain dark because they are empty: no-one is at home; no-one ever was at home. A great many luxury flats in the capital have been purchased by foreign owners purely as an investment; they have no plans to live in them, nor to let them out to others to live in, thus they remain empty, often for years.

Some properties are purchased for more sinister reasons, primarily as a means of stashing away and eventually laundering funds that have in some way been generated improperly; sometimes wealthy owners, keeping on the right side of the law, simply plan to grow ever richer as they benefit from a seemingly unending upward trajectory in London property prices. In these days of low interest rates, high-end London property offers financial returns superior to virtually any other respectable form of investment, save for the most speculative and hazardous ventures.

With but few exceptions, Britain’s most expensive homes are to be found in central London, with the boroughs of Westminster and Kensington & Chelsea frequently featured as the UK’s most expensive places to live. Here, in sequestered, treelined streets, there are blocks of flats worth more than whole streets of houses in provincial towns, and the prices of land and property in these areas seems just to keep rising. The rapidity with which these properties increase in value is such that foreign investors feel no inclination to rent out their places - for years, they remain dark, unoccupied and ever more valuable. These are safe, fecund havens for overseas investment capital, not properties for normal people to make their homes in.

Just as prices at the top end of the London property market have entered the stratosphere, so it has become well nigh impossible for ordinary Londoners to find anywhere to buy: the deposits necessary to mortgage most houses and flats are now unattainable, even for well-remunerated, professional couples, and the relentless rise in property prices has also distorted the buy-to-let market, sending the cost of renting through the roof - a situation made even worse by the fact that demand constantly exceeds supply. We have allowed massive overseas investment to skew the market, a market that will always ensure, naturally, that maximum profit is made without any regard for social consequences - after all, the market is amoral, it has no conscience.

It is becoming generally accepted that London’s housing market is thoroughly dysfunctional and is often now cited as a positive disincentive that prevents talented young people from coming to the capital to work. It is also a clear demonstration of how unregulated markets are often not free markets at all, as the dogma of some orthodox economists supposes, and how they fail to work in the best interests of most people. Such markets are mostly rigged in one way or another by international corporations and/or the mega-rich who create monopolies or cartels to steamroller small businesses and little people, all the while chanting the mantra of liberal economics, that it is impossible to interfere with the operation of ‘The Market’.

The House of Commons Briefing Paper (October 2016), Foreign Investment in UK Residential Property, indicates that the true scale of the overseas acquisition of houses and flats in London is difficult to estimate simply because so many purchases are made, not by individuals, but via complex networks of companies, many of which are registered offshore, or by individuals whose real identity or indeed domicile is almost impossible to ascertain. The paper does, however, reveal that 49% of prime London sales worth over £1m were to foreign nationals. More up-to-date statistics suggest that nearly 60% of new housing created in inner London is marketed and sold off-plan in the Middle East and in East Asia.

Nothing illustrates the crisis of London housing, and the absurd consequences of letting an unregulated market determine how we are to live in our city, as much as the recent, tragic Grenfell Tower inferno, where 72 residents were incinerated on 14th June 2017. This block is located in one of the richest and most exclusive of London’s boroughs, Kensington & Chelsea, and its conflagration illuminates everything that is rotten in our town planning policies. According to a piece in The Guardian, of 12th October 2017, four months after this horrific event, the Local Authority was still struggling with rehousing the 203 households made homeless by the fire: of these, 111 have accepted offers of either permanent or temporary accommodation, with 54 households having already moved into their replacement accommodation. This leaves 94 households who have yet to accept accommodation of any kind and remain temporarily lodged in bed & breakfasts and hotels, simply because the Borough has insufficient accommodation that is suitable and vacant.

One could argue that most local authorities would struggle to cope in similar circumstances; however, a closer scrutiny has revealed that 1,652 properties in Kensington & Chelsea are listed as unoccupied - the true figure may be higher. More than 603 of these vacant properties are recorded as having been vacant for more than two years, and over one thousand of them are classified as unoccupied and substantially unfurnished.

Of course, it would be simplistic to argue that some of the Grenfell Tower homeless should be moved into a vacant property owned by the former Mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg, who bought a seven-bedroom Grade II-listed mansion for £16 million in 2015, or into the 26-flat mansion block owned by Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the vice- president of the United Arab Emirates and ruler of Dubai, or into the many similar properties. However, The Guardian has discovered that there are, in fact, 64 homes listed as vacant in Notting Dale, close by the burnt-out shell of Grenfell Tower. Why can these homes not be brought into service, even temporarily?

At the very time this article is being written, a large area in previously neglected Vauxhall is nothing less than a forest of cranes, cranes that are transforming this formerly run-down quarter into what some have christened ‘Dubai-on-Thames’, or London’s ‘Manhattan’. Arriving here first was a high-rise, 50-floor residential skyscraper, the St George Wharf Tower (popularly known as the ‘Prescott Tower’ after John Prescott, the then Deputy Prime Minister, who controversially overruled the local planning authority and approved its construction). This building, with its spectacular, dramatic views over London, also boasts some impressive and advanced environmental and energy conservation features, generating a proportion of its own electricity and deploying carbon-neutral systems for heating & cooling interior spaces. This iconic building on the banks of the Thames is also energy-efficient in a way not exactly envisaged by its architects: it is mostly unoccupied and dark. Robert Booth and Hellen Bengtsson, in their Guardian article of 24 May 2016, disclosed that almost two thirds of the flats in this towering apartment complex are in foreign ownership, with a quarter held through secretive offshore companies based in tax havens. While the first residents arrived in October 2013, most of the homes remain unoccupied or are used for only a fraction of the year.

The Prescott Tower’s five-story penthouse is reputedly owned by the family of former Russian senator, Andrei Guriev, and as a result of its lengthy refurbishment, it has yet to be lived in. Guriev is believed to be installing a Russian Orthodox chapel inside his new home, and this has had to be carried up in the lift, piece by piece. Other luxurious apartments are owned by Ebitimi Banigo, a former Nigerian government minister, a Kurdish oil magnate, an Egyptian snack-food mogul, an Indonesian banker, a Uruguayan football manager, and a Formula 1 racing driver. The Guardian also discovered that not one of the purported residents of the 184 flats is registered to vote at the local Town Hall. “At least 31 of the apartments have been sold to buyers in the far east markets, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and China; 15 were sold to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates; and others were sold to buyers in India, Iraq, Qatar and Switzerland.” The Guardian’s list goes on to mention Vitaly Orlow, a Russian fishing tycoon, based in Hong Kong, and Sharshenbek Abdykerimov, a former MP and powerful businessman from the former Soviet Republic of Kyrgyzstan.

London’s new mayor, Sadiq Khan, has made speeches about cracking down on the foreign ownership of new homes in the capital: recently, he said: “There is no point in building homes if they are bought by investors in the Middle East and Asia. I don’t want homes to be left empty!” Many Londoners would share his view but the Mayor of London has little else to say on the matter. His office overlooks both the City’s old ‘square mile’ and the Isle of Dogs, where the City’s powerful tentacles have extended to the East; these two financial hubs manage billions of pounds (and other currencies) and it is the City’s big operators who largely determine what happens to all of us. The City of London is one of the world’s largest financial centres and it is intimately connected with the financial worlds that exist offshore, to where vast quantities of untaxed profit are channelled and from where much of London’s most expensive properties are purchased. The beneficial ownership of the companies operating from these tax havens is almost impossible to trace, even by government agencies on such occasions as they are minded to investigate. Some observers have also suggested that London has become the biggest and most trusted international laundromat for dirty money and thus is favoured by the world’s wealthiest and most powerful individuals, keen to conceal their wealth. Mayor Sadiq Khan will have his work cut out for him if he is to effect any change in the use of the London property market for ‘parking’ capital (clean or dirty) - holding one’s breath for early change on this front might well be ill-advised.

In May 2016, The Guardian and Business Insider UK disclosed that the number of London properties owned through offshore companies, based in tax havens, was on the rise, having grown by over 10% in a period of twelve months. “Nearly 40,000 residential and commercial properties in the capital are now owned by companies based in tax havens such as the British Virgin Islands, Panama and Jersey. … On an area-by-area basis, Westminster and the City of London have the highest overseas ownership, with as much as 10% of all property owned by companies based in tax havens.… While the offshore ownership of properties isn’t something that is confined just to London, the capital is home to more than 40% of all the UK properties registered as being owned by companies based in tax havens.” The article continues: “Foreign ownership of property in Britain, but particularly in the capital, is becoming an ever more pressing issue for politicians … all citing increasing numbers of properties being in the hands of super-wealthy individuals from overseas as a major problem for the market. Rich owners from overseas are blamed for helping push prices up, pricing out British buyers, and for encouraging developers to focus on building super luxury flats, rather than affordable housing for regular Londoners.”

But political rhetoric and realpolitik are two different things entirely, as we all know. While it is becoming obvious to some that the increasing number of London properties in the hands of the super-rich from overseas is a major problem for the capital’s housing market, some of our most prominent politicians are touring the Far East, the Middle East, and other countries perceived to have surplus cash to invest, inviting and encouraging the investment of these funds into Britain. Britain is not only ‘open for business’, it is literally ‘for sale’ - to any bidder. We don’t ask questions and we have the best estate agents and sales facilitators, the best financial advisors, property lawyers, and developers, and we keep on developing - as more and more steel and glass towers rise towards the sky, so profits head heavenwards too. And don’t expect our politicians to step in and interfere with these current trends: political parties of all colours are generously financed by those who benefit most from all of this. After all, this is business and as we well know, our Government is mostly interested in business; interference in the ‘free market’ is unimaginable.

The average London house price is now more than half a million pounds, roughly 16 times the average salary. That ratio has never been higher. Developers and speculators hold most of the land where affordable homes could be built for ordinary Londoners, but what motive would they have for releasing this when they can simply wait for the opportune moment and develop a premium block of luxury flats, to be sold to foreign buyers even before the London sales office has opened? They are in business to maximise profits after all.

Politicians do pay the price for their actions (or inaction) in the end; they all lose power when the electorate has had enough and throws them out of office. But as we have seen in recent times, many of them simply move to senior executive positions in the world of business - ineffective game keepers become successful, highly-remunerated, well-informed poachers who know how to manage the markets, and sometime politicians reappear as key players in the worlds of property and financial services.

So there we have it: every day we can admire London’s ever more dramatic skyline - impressive towers reaching into the clouds - but many of these glass palaces will be no more than outlines in the sky. They are just architectural piggy banks for the super-wealthy whose names we are often not even allowed to know. Mind you, why should we need to? Most of us will never know the name of the young man in Brixton who is forced to live in a garage at £100 per week. Some would call this the natural order of things; some might call it ‘Social Darwinism’; I prefer to use a plain English word, it is just the way of ‘the MARKET’.

Text edited: 14th October 2017