Читать книгу Londoners at Home: - Milan Svanderlik - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

WHO do we live with? BOOMERANG GENERATION

ОглавлениеBecky Ross at home with Janet Ross and Bjørn Harald

It is symptomatic of some of the problems of our age that when children have flown the family nest to go on to university or other education and training, they are subsequently obliged to return home. ‘Boomerang’ graduates struggle to find anywhere affordable to live and must of necessity put on hold the continuation of an independent life. Both Janet and Bjørn are pleased to have Becky back and partly because their work patterns are very different, they can all coexist in perfect harmony. According to the Office of National Statistics, a total of 3.3 million 20 to 34 year-olds were living with their parents in 2013, a figure that is still rising. The official figures show that the number of young adults who live with their parents (many of whom have ‘boomeranged back’ after university) has increased by a quarter since 1996, with high house prices, escalating rents, and limited employment opportunities as the main reasons why many are forced to remain in, or return to, the family home.

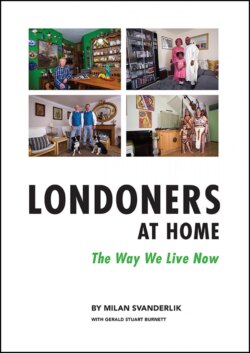

Photograph: Left to right - Janet Ross, her partner, Bjørn Harald and Janet’s daughter, Becky Ross at their west London home. (Photography: 3rd January 2017)

The full story:

The comfortable, professional lives of Janet Ross and Bjørn Harald, living at home in Aberdeen with two daughters, could in many ways be seen as thoroughly conventional. Janet noted recently: “When your daughters leave home to go to university, you experience the usual ‘empty nest syndrome’, but even though you have expected it, going through the feeling yourself is another thing entirely. Once the girls had gone, we felt it was time we had a change too and, after living in Scotland for over 15 years, we decided to downsize, moved to the south, and bought a flat in West London, which is where we live now.”

Janet’s daughter, Becky Ross graduated in Economics from Edinburgh University and, while she had a firm intention to embark upon the development of her professional career, she also wanted, as many new graduates currently do, to explore the world a little bit first. She spent almost a year travelling New Zealand, the Far East, and for an extended period in Australia, a time that was both great fun and also professionally useful, considering her hopes and plans to pursue jobs that would have some international reach.

In the meantime, Janet and Bjørn settled into their west London mansion flat and started to enjoy a new life in the metropolis, little expecting that Becky would soon be boomeranging from Australia back into the parental home, ironically to become a member of what is known these days as the ‘boomerang generation’. Now working in London and taking her first serious steps towards what she hopes will be a successful, professional career, Becky was faced with the daunting prospect of London’s unaffordable property prices and almost equally prohibitive rents. She was not keen, at the age of 24, to go back into flat-sharing, with the irksome and disagreeable limitations that sharing frequently implies, or into the dreariness of a seedy bedsit, all too often associated with the indigence of student life, so Becky moved into a room in the spacious new parental home. Both Janet and Bjørn are pleased to have her back and partly because their work patterns are very different, they can all coexist in perfect harmony. Unexpectedly, they now figure in some interesting new UK stats: accordingly to the Office of National Statistics, a total of 3.3 million 20 to 34 year-olds were living with their parents in 2013, a figure that is still rising. The official figures show that the number of young adults who live with their parents (many of whom have ‘boomeranged back’ after university) has increased by a quarter since 1996, with high house prices and growing youth unemployment as the main reasons why many are forced to remain in, or return to, the family home.

Becky has been welcomed back and is equally pleased to be at home again; she admits, with a big smile: “It’s a very comfortable home and the support of my parents really helps me to concentrate on my job. I am able to save some money, the fridge is always magically replenished, and even the washing seems to get done for me somehow.” It is obviously a happy home for all three of them.

But the experience of others is often less positive. Some parents feel that after the kids have left, they regain a sense of autonomy, finding more time for themselves and perhaps even spending a little more on their own pleasure, or boosting their savings as they plan for retirement. When their children return home, that new-found independence is lost and they feel responsible again; their finances are once more under pressure because young people can often struggle to find jobs, or jobs that are sufficiently well remunerated.

Bright young men and women used to dream of a life after university that somewhat resembled episodes of Sex in the City - lots of fun parties, eating out and a fashionable life in a designer apartment. Back home with their parents, it could hardly be more different - they feel like teenagers again, with the parents watching their every move, fretting about their future, and affording them little privacy. House prices in London seem ever-increasing and almost no-one on an ordinary wage can now sensibly dream of owning their own home. Jobs are hard to get and even when they are found, the contracts offered are increasingly insecure, with fixed-term and so-called ‘zero hours’ contracts ever more common. With such financial insecurity, young workers have little hope of getting a bank loan or a mortgage. On top of these impediments, graduates are burdened with the repayment of the huge debt represented by their student loans.

It is hardly surprising that the ‘boomerang generation’ feels anger, disappointment and sometimes despair at their dismal situation, as if they were imprisoned in a world that has no opportunities for them. In this lamentable predicament, some young people become irritable, depressed, and deeply anxious about the future - having their own home, with their own family growing up in it, is a future that they just cannot see as a prospect for them. Of course, some will work exceptionally hard, some will be lucky and secure a well-paid, permanent job, and some will be able to call upon the ‘bank of Mum and Dad’ to get them on the housing ladder; but others will just give up, lose hope and any kind of motivation, throw in the towel, and finally opt out of a society that seems to offer them so little. Surely no decent society can prosper when such are the circumstances that face so many well-qualified and highly motivated young adults unless, of course, one takes the view of the ‘social Darwinists’; they seem quite content that the unfortunate, the underprivileged, and the weak should be left to perish, while by contrast, the fortunate, the strong, the successful and the rich are allowed to prosper. These privileged classes lay claim to the ‘good life’ that seems fated only for them.

Interview date: 3rd January 2017

Text edited: 4th January 2017