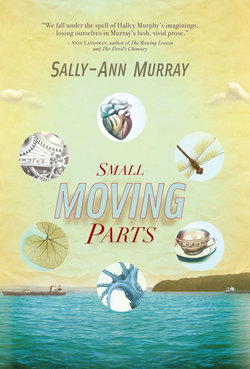

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Close-coupled

ОглавлениеAfter the baby, when the balcony unit off the Ridge proves too expensive, Mark and Nora move to the corporation flats. Kenneth Gardens. It’s Nora who finds the place, makes enquiries, takes her warm plate of pleas and thank yous to the official in the council office.

Though some people aren’t interested in listening. Mark’s friends, for instance, who are all too ready to make the new Murphy home at 4 Ixia Court into a den of thieves.

Nora doesn’t want them there, she tells Mark. Your cronies. A crew of ne’er-do-wells.

They bring bolts of fabric, wrapped in tough plastic, sealed cardboard boxes – goods they’ve skimmed from whatever ship they’ve been jobbing.

But Nah, it’s nothing, one of these chancers will say, You must just tell Mark to only keep it for a bit. Stash it till things cool off. He doesn’t have to move it or any.

So his mates always knew where to find Mark, and where to get tanked on the friendly beers he provided. But if they stopped by to drop off goods and Mark’s wife asked where he was, then they were close-mouthed against her questions, tight as mussels.

All they’d do was mock, joke like a brash of boys while they waited, toasting their dewy, golden bottles in the baby’s direction, laughing, always so much laughing. How Mark Murphy was a bladdy good seaman, and nobody can deny. Another peal unbottled for all to enjoy.

Halley never knew to laugh or cry. She was much too small. Just a baby. Yet even now, as she recalls her mother’s tightly knuckled face, it doesn’t sound funny.

Soon, the little Murphy has grown some, though she remains a bony, unappealing infant; never the sugared dainty of the preferred female standard.

Nor is she anything like the little blighter the father was expecting, just as he is nothing like the husband anticipated by her mother, so maybe things even out. But all this is of little account, and for the present Mark is gone. Somewhere up north. A job in Rhodesia.

Where if he didn’t realise it, Nora curtly told people who asked, There was no ocean, so no openings in the ship repair business.

Maybe he was planning to turn his hand to something else? Aunty Beulah from upstairs suggested, meaning find his luck or chance his arm, her faith in heavy engineering, if not in Mark, not completely undermined.

Now, now, Nora, she’d soothe, Could be that up there the going’s good? Some spin-off from Kariba, you know, which is a lake, after all. To a boat, she reminded her friend, Water is water, no?

Yes, said Nora, Because it has no need to slake a thirst.

The baby is hard work for the mother, with that thin, persistent niggle, and a tendency to be awake when most households are dead asleep. Often, the child still shuns the breast, so could be it’s lack of food that keeps her wailing.

What does she want, Nora grates, Why won’t she sleep? Cannot be teething: she’s too small to be cutting teeth.

Long, dark nights, Nora holds the wailer over her shoulder on the narrow back porch. Up and down she sleepwalks, one way then another, keeping watch, tramping grooves in the wooden floor like a trolley track, pat pat patting the baby’s ribbed back.

It’s only exhaustion that keeps her from hitting harder.

Soon the fractious patterns are established, and Nora cannot keep herself from thinking she’d been mad to want a baby. And that if she had wanted a baby, it certainly wasn’t this one. But imagine wanting any baby with that man, she stirs herself up, all defiant. And in this crazy country! Why are women so stuuupid? she wonders, angry enough to join the women who marched on the Union Buildings, instead of falling in love. But she’s missed that boat by years, she knows, and will never find out now if it was possible to have both.

But she also wants reassurances against politics, and they come, of a sort, through the voice of authority, namely Springbok Radio. On the news, listeners hear that 1960 is a thing of the past; that the unrest had been provoked by isolated Communist agitators and lone rabble rousers. That there is no longer a groundswell of organised black resistance. So the future looks strong, economically and politically. Trouble has been nipped in the bud.

Today will be mild and sunny, the temperature a pleasant twenty-four degrees with the possibility of light showers towards the afternoon.

This is some relief to Nora, the new mother, left high and dry with the baby of her unrest, husband gone AWOL. And the news must be true, isn’t it, because the sun rises, and sets and rises. Every day at sparrow’s the milk and orange juice are delivered as always by the boys from Clover, the trucks noisy as ever; and the dustbin boys and native girls are still coming to work without any trouble. So it seems that ordinary black people know which side their bread’s buttered on.

Or at any rate, like the rest of ordinary people, they’re caught by the short and curlies.

And then, after the referendum, the country is a new republic. So okay, it squeaks home by only fifty-two per cent, but narrow margin or not, you can’t deny the vote’s a majority. Which means it’s time to go it alone.