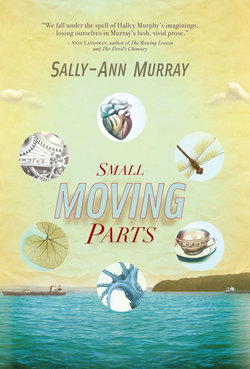

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Rule of three

ОглавлениеWherever she began, numbers were stories. A man was 1. Which meant In the Beginning. It meant The One and Only. And One of a Kind. She was always looking out for Number One, a slight but important figure, scarce as a matchstick in an overgrown field.

A woman was 3. Curved. Curvaceous. But in Halley’s family, their mother became The One, through slow excoriation taking away from her rounded self almost completely to provide for the two little girls. The one raised finger and the only firm footing.

In between were the children, 2. Halley, and Jen.

Daddy was gone, so he was 0. But even nought was something, not nothing. Not a big loser. O 0 ○ was part of a keyhole.

Like escutcheon, which was another part. Her mother said a child was never too young to start learning, so then she explained about the metal shield around the keyhole. For neatness, and niceness, to soften the ugly hole.

Escutcheon, Halley said, fingering the beaten brass on the old kist, the little plate hammered in with the smallest of nails. She added them up, the nails. But the big word only snagged in her throat and exploded against her palate, a poor rabbit caught by its back legs in a terrible trap.

Halley couldn’t believe how many words her mother had. They came out of her mouth and her head and the dictionary and went into the air. Some kinds came out mainly late at night, when she sat at the kitchen table scratching with a pen. She put them into the tiny white squares and they stayed there, balanced with all the others, buffered by the black blocks.

For the crossword puzzle, her mother didn’t like to use a pencil, because that was cheating.

In kindergarten, Halley wrote 1 2 3 4 5 on a fresh page. She shaped each numeral perfectly, because a number was a beautiful shape. Shapely as Aunty Sybille at the flats, with her hourglass figure.

In class, the children were allowed to draw whatever they wanted next to each number. The only rule was to match the numeral and the number of things.

Halley crayons

1 (next to) picture of a diamond ring

2 (next to) picture of an ice-cream cone picture of an ice-cream cone

3 (next to) picture of a mouse picture of a mouse picture of a mouse

In this exacting task, Halley’s work was most exactly done, both correct in number and incredibly detailed, because Halley liked making pictures, and she loved how numbers and pictures formed a series of relationships: 1 *, 2 **, 3 *** , a wonderful linking of lovely and logical.

She was extremely satisfied with what she had discovered. This was a worthwhile thing: I can have the number and the picture! Both together! Two for one, which equals some extra.

That’s how Halley tried to think things through, always wanting more, and weighing up effort in relation to returns and factoring in bonsela.

Already, she’s learnt important things. How every number has its own word, and that a simple letter can do magic, changing ‘cat’ into ‘hat’.

But, really, she’s always known that language is tricky. Like when their mother says to her daughters one dark morning, You don’t have to get up yet, girls, it’s still old and curly.

Jen says What? just with her face, while Halley feels herself floating for a moment, she’s not sure where. And then suddenly she and her mother realise. And the language, this time, is a delicious, shared joke.

From the first, the report cards are carried home as if by angels, a white page shining through a sealed brown envelope . . .

Davaar Kindergarten School

A little work, a little play, a lot of love and that’s the day

Name: Halley Murphy Age: 3 years and 5 months

Halley is a joy to teach. She is eager to learn and applies herself to every task with great enthusiasm. She is an excellent all-rounder who shows an especial aptitude for language, nature study and art. Halley needs to be kept very busy, otherwise she is inclined to fidget and wander off. She is always polite and neatly dressed. (A credit to her mother!) She enjoys her own company and keeps her own counsel. Halley must be encouraged to guard against a tendency towards over-seriousness. Instead of thinking so much, she should play more with little girls her own age, and learn to be a child. However, we have been delighted to discover that she is a natural actress. When she is so inclined, she engagingly entertains both teachers and peers with amusing skits of her own origination.

Miss M Milner

PRINCIPAL

So. From the beginning, the collected sum of herself.

Sometimes, when they have to sit quietly on their small chairs in the prefab classroom and listen, Halley hides her hands under the baby desk and uses the Tommy Thumb of each hand to touch the tips of the fingers on the same hand, repeatedly counting in her head while she listens to the teacher. She goes 1-touch 2-touch 3-touch 4-touch and immediately after that she shifts the power to Peter Pointer so she can leap from Baby Small and include the thumbs as 5-touch. All in secret.

Under the table on the floor inside her socks inside her shoes, both feet fidget out the same time, counting in order to make connection. Yet she is not calculating; only making patterns to stop her mind from wandering.

Sometimes they stand outside in their knickers and vests and do exercises. There’s even PE for the fingers. Stretch and clench. Halley’s fingers are long, and so flexible she can disarticulate from each fingertip, and push her rubber thumbs back to reach her wrists. In her mind she’s Twangy Pearl the Elastic Girl, but Halley can see that Miss finds both these tricks disconcerting, though whether it’s her authority or the limits of human physiology that are being challenged, how would Halley know.

You must be double-jointed, dear, the teacher says, as if that explains everything, but it only serves to keep Halley guessing. What does ‘must’ mean? Is the teacher’s remark based on what she has observed, thus constituting a statement of fact, or is it a guarded injunction, even a warning? Is that what the exercising children are being trained to master, absolute lability?

Halley keeps expecting that she will be asked to perform something impossible, and perhaps it’s this unexpressed anxiety that has her bending over backwards to please those who have the power to dish out or withhold reward. She would prefer to pre-empt imagined punishment, if that were possible.

Though they do not become her single definition, the flats in Durban define her girlhood. She lives in Kenneth Gardens, the corporation flats. If someone asks, Where do you live? Halley hesitates to admit, because all she has to say is Kenneth Gardens and people will know exactly who she is.

Her mother says the flats started out as a place for the Durban Corporation to help white soldiers when they came back from the war that time. Later, though, when the soldiers were finished, if you worked for the corporation – like a clerk or a bus driver or something – then you could put your name down on the waiting list.

Even later, by the early 1960s, the flats have become a popular choice for struggling whites, which means their address is the bane of her mother’s life. For Nora Murphy, the other tenants in Kenneth Gardens bring white poor perilously close to poor white, which is much too close to the bone. It’s a stigma that has been sniffing around her impolitely from the day they moved in, indolently lifting its leg whenever and wherever it will. Though Nora realises, where she’s come from, that she’s brought some odour with her. It’s something she’s been working hard to eliminate. All telltale smells and stains.

Yet despite all Nora’s efforts, here she is, living in Kenneth Gardens. By now, really, she had expected to have come much further.

Nora Patience Murphy (née Hoare) is near the tail end of thirteen children, the last bar one, born in Port Elizabeth and shunted to Durban. When she was five, Nora and all the young ones but Milton, still a new baby, were removed from their parental home and taken into state care. The boys went who knows where; the girls were kept together in a convenient handful, a short while in the Durban Children’s Home, and then shipped off to St Faith’s, an orphanage in Bloemfontein.

Where you had to have it, and keep it, faith, but it was damn hard, that hard home of your childhood. Though Nora is still on the right side of thirty, and has spent her whole life trying to improve on her bad start, things have not really panned out, yet, her plans, and surely she has grounds for complaint. But she doesn’t complain, not often, or at least not outside her head. She just keeps at it. For now, Ixia Court is the best she can do, so she does it.

Faced with her little family, she makes a home. She becomes unbelievably resourceful, industrious to the point that her voluptuous, womanly body pares down. Not to bare bones, at first, but to a lean muscularity.

And even after that she still had a way to go, and off she went.