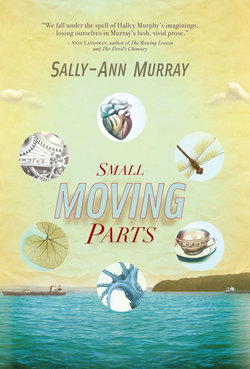

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Gardens

ОглавлениеWhen they were making plans, the town planners probably imagined Kenneth Gardens as a gesture of green faith in human nature; a garden suburb, the sure, civic-minded sign of change for the better, countering war-weariness.

During construction, to soften the look of brutal housing estate, some mature trees are retained, then the spacious grounds are planted with flowering shrubs, indigenous and exotic, the entire world in this green shade, giving space for families to grow. Numerous frangipanis and jacarandas. Lucky beans. Yesterday-today-and-tomorrow. Poinsettia. Pride of India. Some dense thorny elms, and the sparse, jagged towers of darkly louring Norfolk pines.

More homely are the names of the flats, since each block in Kenneth Gardens is named for an indigenous flower, the letters bevelled into the masonry above the entranceway. Ixia Court. Like everyone else the Murphys say Exia.

Ixia, Watsonia, Iris, Jasmine, Arum . . . At the time when Kenneth Gardens is built, the flowers are intended as a welcome home bouquet for the ex-servicemen, and they represent the whole blooming bunch of beautiful South Africa, paradise on earth.

By the 1960s, when the Murphys move in, the gardens no longer exist; only the tough old trees soldiering on near the wash-lines, and down in the park. So the names of the flowers carved into the plasterwork are merely the mark of a person’s address. Ixia. It’s where you live.

Since the gardens are long gone, it’s the wash-lines which dominate. Every day, there is the burden of daily washing weighing down a woman’s arms, and then pegged onto the plastic-coated wire strung from metal T-bars. Only the dark provides relief, as then the lines become invisible, despite some things being left to hang around all night. A saggy bra. A lone pair of limping trousers, slowly dampening home into another pegged-out day.

Every kitchen door opens onto the shag of grass strung with communal wash-lines. Nora hates it. Hates having to look at other people’s washing, dirty or otherwise. Nora prefers privacy – why should it be a privilege? There are things in life you shouldn’t have to see. But with the wash-lines you’re as good as walking around naked, since the neighbours can see your business out there every day, without even the trouble of having to pry.

Boys and girls swing on the gibbeted T-bars and run through the washing ka-flap ka-flap, their arms outstretched. They carry on even after they’ve been shouted at. Halley too, if there’s no chance of being caught. Because it’s fun. The quick brush and fast pull past of fabric which lets you pretend different things, like you’re hitting people, or trying on their clothes, or you’re putting your spirit into what they’re going to wear. That’s how much power you have. I am in . . . vin . . . ci . . . ble!

But also you can get frightened among those rows. The cloth smothering your face. And the washing can turn on you, especially if it’s a windy day.

Once, they’d gone visiting with friends to a house past Durban North, and bold Halley took all the children exploring in the nearby cane fields. Somehow, she got them lost. Halley was so so lost, but couldn’t let on. What happened? asked the worried adults later, demanding an explanation.

She couldn’t say. All those horrible hours pretending to the kids that you knew where you were; so conscious of the day getting shorter, the night drawing in like hidden cane rats, waiting to attack.

So sometimes, when she looks at everyone’s clothes on the lines – there’s Aunty Beulah, there’s Sheila and Belinda, there’s Uncle Zach, there’s . . . there’s me! – Halley understands the idea of emptiness, of herself as inside out.

Halley has the Weet-Bix flower card collection. A series of 100 cards issued by arrangement with the United Tobacco Companies. There are also mammals, and fish. She has these too.

Nora often gives the girls Weet-Bix cereal for breakfast, since Weet-Bix is very filling. It is an economical food, especially high in fibre, and it keeps a body regular. You can’t be too careful on both these counts.

Halley contemplates the Weet-Bix in her bowl. A single biscuit, doused with warm milk, swells to double its size. The process is good as a biology experiment, digestion just about occurring in front of your eyes. Which makes up for having to eat cardboard.

But Halley wants the flower cards, so she eats Weet-Bix. Lots of. Then she cuts off the end flaps and pastes the pictures into a special album to make her own book. Our South African Flora, it’s called, and it is full of interesting information, selected and arranged for you by actual scientists. You only have to fill in the blanks.

The cards and the album are part of an educational brain system which helps to make your head full of ideas. This suits Halley fine, as she is already consumed by seriously big thoughts. She’s read one book, see, about people trying to live through the Second World War? And there were such terrible things happening that it didn’t seem shocking even when soldiers tore pages from The Bible! for rolling their cigarettes. Man cannot live by bread alone, she knows that. Also, she found that article near next-door’s dustbin. From an old Scope magazine. About a strange girl who refused to eat anything but paper, so that she felt full without getting fat.

The Weet-Bix flower cards are fun. They give you something useful to do with your mind, so that you don’t seem like a cow while you eat. Years later, however, she can’t remember one thing she ever learnt from them. Nothing about flowers. Nothing about Ixia.

She was such a bookworm, Halley Murphy, curled up among her papers and pages, but she didn’t know that she was housed undercover, beneath the sign of an indigenous flower. All those years she’d lived under the cover of Ixia, a secret, flower-fairy greenery which covered itself, along with everything else.