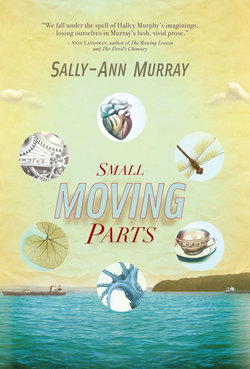

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Name-calling

ОглавлениеWhen her second labour begins, Mark’s off again somewheres, still hopelessly seeking his fortune. Nothing new there except a new baby which tips the scales at a hefty ten pounds and some change. A girl, again, but feisty this time, and a real devil to deliver.

This child is constantly hungry and she clamps to her mother with a gusto that goes beyond hearty, a warning clear enough for anyone to heed. The hospital staff cannot credit their ears. What newborn screams like that at its mother, shattering the hard-won quiet of the general ward? That’s some pair of lungs, god forbid, and the fed-up face on her!

I want more! this baby yells, regardless of the rebuking stares, its mouth a violent cavity opening into a deep maw. More! Gulping greedily – nipple, air, milk – until the plump chin is crusted with curds and her body, saturated for now, floats, farts, puttering into the swell of a choppy history.

Though Nora’s had it with history for the present. How it has no respect for privacy, ignores doors, closed or otherwise, rather like the extremes of Durban weather.

Just the week before, driven by that pregnant urge to tidy the nest, she’d been sorting through Mark’s musty clothes, the signs of his long absence taking up too much space in her heart. And wouldn’t you know it – in the pocket of his sports coat, there it is. The blasted love note that detonates the little she has. She slumps on the lino, letter in hand, her pregnant stomach swilling like a buoy in the wake of a bulk carrier, all the world’s flotsam bilging on the surge.

But she pulls herself together and recovers her equilibrium. She’s not finished by the blast, and nor does she lose a limb, though for that moment she feels torn apart. And likely looks it too, she hmphs, pushing the ragged hair from her face.

However, she’s not dead, for heaven’s sakes. Am I dead? she asks the woman in the mirror. I am not.

It would take much more than this to do her in, so yes, the written evidence being small enough and her own insight now hard won, her life remains intact.

Although she cannot deny how suddenly it hits her: that this is all you have, how history is all you get to live in, the hard times and missed places. A big box of small moving parts which is hard enough for anyone to carry, and certainly ought not to be handed out without warning. Would it help, she wonders, to have a label that says This is not a toy – it can kill you? Who knows, people do what they want, warning or none. Some days, though history can seem so terribly ordinary, a moment that begins before you even realise it, there comes the instant you know what you’re holding and you can’t put it down; then you can’t stop yourself from thinking that the point of it all is only to get you dead. Or at the very least to leave you crying, and falling apart.

Whatever it is, in the morning the carpet is darkened by a patch of wet that must be cleaned, and with all that’s happened in the house of the world, it’s not so hard to believe that this is blood.

When the father comes round again, chastened for the mo’ by another failed enterprise, he once again wriggles past his evasions and he and Nora kiss and almost make up. It’s then he meets his second daughter, by which time it’s way past the date to register her birth.

To correct his paternal lapse, Mark Murphy makes his way downtown to Home Affairs, and he is channelled into the appropriate line, where he must wait along with all the others who require certificates of birth, and death, identity books, and the various species of paper which will entitle them to pass into the public record.

The Murphys have decided to call the infant Jennie, and the father, inspired by fresh starts and new leaves, queues with unusual patience to enter this piece of very ordinary information in the requisite government register.

He stands inside, dreamily thinking. Looks at the big clock on the wall; the sparse, balding scalp of the man in front; the sign which says Oswald Pirow Building. Finds himself chuckling at the ridiculous thought of ‘Oswald’. Imagine! What a name! Not what he’d call any son of his . . . If he had a son, that is.

Still waiting, to pass the time he hums an old English country air that’s been enjoying a popular comeback. ‘I dream of Jeanie with the light brown hair’, words and tune lilting in his head. For a moment, he almost begins to sing aloud, carried away by the catchy, silent soaring. Then he thinks of his sister Norma, the surprise of how the baby resembles her. Remembers the car accident in which Norma died, on her way back from a twenty-first bash with her boyfriend.

Mark, musing, waits so long in the tedious queue, so mindful of the pretty melody and the sad descant of his dead sister, that when he arrives at the counter and must provide his daughter’s chosen name, he gets flustered. He’s been far away, plus spelling was never his strong point. Many things have had to be spelt out for him, and even then . . .

So on the form he prints ‘Jeanné’. Steps back from the word a pace and slightly cocks his head. Looks at the man behind the counter who is studying him quizzically, on the verge of impatience.

Humh. Does that look . . . can that be right? Mark squints at his efforts, then laughs. Oh well, can’t take it back now. What’s done is done.

The clerk ratifies firmly. Stamp!

And thus Mark shackles the baby to an impromptu title which no one will ever know how to pronounce, or spell. When calling register, teachers will hesitate over ‘genie’ (maybe?) or (could it be?) ‘zhjaan’, or (possibly?) ‘zhjannay’. Perhaps it is merely ‘jean’? They are unable to reconcile the exotic spelling with the child’s curt, plain-spoken correction. Jennie. Really! People are affronted. Was such rudeness called for? Jeanné takes to spelling the name how it was meant to be, aloud, as if for some mentally deficient chump: jay ee en en ai ee. Pretty simple, huh? Though teachers, especially, consider her a liar or an idiot when they try to reconcile the vowels.

But Jennie’s logic is clear. She is completely intolerant of learning; sees no point if even careful spelling and enunciation cannot teach teachers the absolute basics: how to recognise her name. No wonder she doesn’t answer when called. The music teacher will be particularly perplexed: it is completely beyond her how a child with an exquisite soprano and perfect pitch can seem deaf to her patient, inspired instruction.

Mark, having stood in the queue in that abstracted frame of mind, and then at the last minute feeling slight panic at his undeniable sense of having messed up, again, also decides, without running it past his wife, hell, why not, he’ll give the new baby a second name, which is Norma, after the tragic sister. Somehow he thinks that this will ease the ruckus that’s going to be raised when he gets home and has to hand over the birth certificate, which will show another misnomer confirmed by official pink ink.

Ever the cock-eyed optimist, he reckons blithely that look, if Jeanné won’t do, the wife not happy with that, at least there’s a back-up. Quite sensible, really, and he starts to feel almost chuffed.

Norma. Will do the trick, no? Was a good name, that, good enough for his sister. Busy reasoning, he even convinces himself that ‘Norma’ marks an important gesture towards family tradition, and is some compensation for the fact that with their first-born he and Nora hardly knew what they were about, having had on the spur of the moment, as it were, to find a suitable name for a girl. This time he’d wised up, kept his options open and didn’t count his chickens.

He seems to forget, however, that his wife is not one to tolerate either male ineptitude or a man’s foolish flummery, not to mention his relations, so why he thinks she’ll be placated by ‘Norma’ is anyone’s guess. Nora is sick of Mark and his stories, and would like him to grow up.

But anyway, now it’s Jeanné Norma’s turn to start growing, and despite her father’s subsequent ridiculous fancy, a false memory par excellence – that yes, indeed, the name of his second was inspired by Norma Jean . . . Marilyn Monroe? – she grows increasingly to resemble the deceased sister. Jennie has thick, black-brown hair that frames her delicate face in lustrous waves, her eyes are dark and sultry, and there’s the mouth that makes no concession to propriety, sulky and sexy by turns.

Soon, she’s two years old, but even as a toddler, Jennie is a siren. Most unlike her sister, who at three can whistle like a boy and already likes to trumpet her own importance.

Atavistic Jen is how the Murphy women are supposed to look, although the family has historically been predisposed, by preference as well as genetics, towards males. But as Jennie grows she repeatedly tries to tell people, No, she is just herself. They must stop comparing. She starts off so completely herself that this is how she remains; not even her two names are enough to hold her back, keep her in the odd relation that people have fixed for her. She shrugs off the ghost of the name. She is Jennie. She is Jennie on any and every document, naming herself as she’s been doing since she knew her name and was able to talk. If there are queries, which inevitably there are, given the discrepancy, and her birth certificate or ID must be produced to verify her identity, she produces it, blaming the inexplicable on her crazy parents.

Families, shrugs Jen, the whys and wherefores. They cannot be explained.

Names are quite a thing for the Murphy family. Something so simple, you’d think, but they find it hard to get right. So they don’t, really, and whatever you’re called, you simply have to live with it.

Though when it comes to names, Jennie and Halley have different strategies.

When the newlyweds were taken by surprise that their first-born was a daughter (meaning, mainly, that Mark was so fixed on a boy he hadn’t stopped to consider the only other alternative), the unborn son was already called Ryan Patrick. Both solid, traditional monikers which would merge nicely, melodiously, with Murphy.

(Though nobody had given a thought to the initials, which would be RPM, enough Revolutions Per Minute to make any child dizzy at the thought.)

And then he turned out to be a she, the wife not turning out a boy, so something had to be done.

The story goes (though maybe someone’s only talking through his hat) that the father picked several possibilities and scribbled them down on bits of paper, then invited his mother to draw the winner from a hat.

Take a chaaance, Mark encouraged, passing the hat as Felicity sat in the lounge at Ixia Court, sipping tea, Why not, Ma? This could be your lucky day. His eyes twinkled, his eyebrows wiggled.

Oh my son, she said, teared with laughter and shaking her head, You and your nonsense! And then she felt, with feeling, and picked.

There is no written record of the odds; nor is it known what the infant’s mother thought of her husband’s impulsive strategy. Though the winner, as you know, is Halley. Which for the child doesn’t feel like her real name, even though she will come to appreciate that she has reasons to count herself fortunate. For she is not Dorcas or Zibbeth or Zillah. Not Winifred or Zenobia. Among these may be good names, even good biblical names, and good enough for some people, but they’re definitely not hers. Not her. Any of these names would be a terrible cross to bear.

She’d heard some rumours that in the hat of names had been Karen and Barbara, two among her father’s scrawled possibilities when he’d found himself stumped for ideas when faced with the flabbergast of a female child.

And that Nana had almost cuffed him, after she’d drawn the lucky winner and was casually going through the hat, checking for the names that didn’t make it. Because Karen and Barbara were recent granddaughters from her other sons, born a few months ahead of Mark’s girl.

What were you thinking? his mother persisted, although Mark’s face was all fallen and forlorn, meaning why must someone always spoil the party.

Or not thinking, as usual! she shoved her silly son hard in the chest. Lord have mercy, did this man have no brains beyond the merest stretch of empty imagination?

In the beginning, when Halley thinks about her name, the fact that most stubbornly demands attention is the idea of the hat. A pebble in the shoe. A mote in the eye. An annoying fly in the ointment.

A hat.

She’d asked her mother, who’d only shrugged at this nit-picking, and observed that hats hadn’t been particularly fashionable for men back then. And Nana? Halley wondered, but she’d never seen her Nana wearing hats. Not even one single hat.

So the hat must have been her mother’s. If it was that obvious, why didn’t she just say so, then Halley could figure out where to start?

For Nora wore hats, many different hats, all of which she’d made herself.

After finishing school, which wasn’t finishing school like some place fancy in Switzerland, only Matric, but actually for a poor female at that time was exceptional enough and one of the upsides of the orphanage, which was sponsored by church and state, when she’d done with high school Nora was enrolled in a six-month evening milliner’s course at the Bloemfontein Technical College, so that she might acquire a socially useful skill.

The fruits of her youthful labour remained in Ixia Court, stored in hinged hat boxes on top of the bedroom wardrobe. In one box, she’d even kept the milliner’s blank form, a funny wooden blockhead without hair or features, little more than a domed crown on a metal stand upon which to shape and balance her decorative craft, though these days she never did.

Halley knew about the headgear, having often seen her mother in a hat. But once, also, she’d gone mining in her mother’s things.

For years, the sisters were convinced that their mother had kept something mysterious from them. And if only they could sniff it out.

So one day when she was at work and the boring afternoon was stretching out beyond the possible, they dragged a kitchen bankie into their mother’s bedroom and stacked a chair on it so as to reach the untouchable hatbox collection stored on top of the high wardrobe.

They’d find something, they knew, because Halley said so. Something would be in there.

And something was. Hats.

Along with a hideous, perversely flattened albino cockroach, scurrying out of one box as if it had been pressed dead but a single chink of light had coaxed it back to life.

With such a skrik, Halley sent everything tumbling, hats, tissue wrappings, herself included, nearly conked on the head by the heavy wooden dummy, and she abandoned all their mother’s things where they fell in a headless sprawl of satin and ostrich feathers and nubbled felt. She quickly slammed shut the bedroom door, as if it might become at once an impenetrable boundary and an invisibility cloak.

After, when she discovered the meddling, Nora was really mad. As a snake. A hatter. A hooded spitting cobra, the images whirled in Halley’s head.

What the heck were they doing, rummaging like that? Fossicking among her things.

That fossilised word, plus the intensity of their mother’s anger, only convinced Halley that Nora really did have something to hide. More than ordinary hidden treasure even.

Plus, the girl had found the letter, folded among the hats, and she’d clutched it in her fall from the tower of boxes when she’d been startled by the monstrous kokkerot.

My dearest Nora, she read later, locked in the toilet . . .

You will excuse my writing to you, but as Mark’s mother I of all women know that he is not an easy man, and that things between the two of you have been difficult. As he tells me, they seem now to have reached an impasse and so I would understand if you threw him over.

I myself, dare I admit, had occasion to experience similar feelings towards his father, who as you’ve heard was a well-meaning but misguided person.

But please, my dear, please. If only for my sake and that of the unborn child: think about how much you love him. Without you, my son is likely to be ruined. He has always been slow to settle, and I fear that you will tip him over the edge when you could just as clearly save him. I know it.

I know my son. He has never loved any woman as much; I have never seen him so besotted. He merely needs a little time to work the waywardness out of his system.

Although I don’t wish to make excuses for him. Only to beg that you allow him a final chance to commit.

He has, I admit, made yet another mistake. One of consequence. Yet he has come clean, has found the humility to confess to you, and apologise. Won’t you be big enough, once again, to forgive him?

Please. Do not abandon him. The two of you can make it work.

And, Nora, you know that love is never easy, especially for the woman. Men are very weak. It is the woman who must be strong. You are strong, determined. I have seen this quality in you already. I admire it, and trust it will be the making of the relationship between you and Mark.

With my fondest wishes,

Felicity

Halley felt breathless, unsure about what she’d discovered. Had to tell Jen.

You can hardly blame Mommy, she said quietly to her sister, I think she wanted to believe in something, even if it was only herself.

Hatbox upon hatbox containing Nora’s creations teetered on high atop the wardrobe. Page upon page of memorable photographs, from before, show Nora wearing her various hats, the neck held erect, finery displayed to elegant advantage.

A newspaper cutting firmly creased across the paper waist: the Mayor’s Garden Party in Bloemfontein. ‘Mej. Nora Hoare was gister op die tuinparty geklee in ’n rooskleurige geëmbosseerde nylon-tabberd, waarby sy ’n grootrandhoed van dieselfde kleur gedra het. Haar lang handskoene, handsak en skoene was wit.’

You didn’t know all what it said, but your mother looked beautiful, all blossomy and poised.

On the reverse of the cutting was part of an advertisement, a line drawing, severed by scissors. A telescope on a tripod, the long length rudely abbreviated, but still putatively trained towards the missing skies. A speechless, cryptic glimpse of something gone.

So, Halley thought, her name came out of her mother’s hat. If so, which one?

The nesting black osprey. The felted grey cloche. The black, beaded, shot-silk with seductive half net and mounted feather hackle. The swirled, pale pink ostrich feather cap, like a marshmallow dusted with shredded coconut . . . ?

A very odd practice, whichever one it was, Halley thought. Hatable.

Though come to think of it, maybe there were valid reasons for pulling a name from a hat, when you recalled that using other, more conventional methods Nana had come up with Matthew, Mark and Luke, for her three close-born sons, meaning that she must always, surely, have had the feeling that another, final son had failed to arrive; that a boy called John had gone missing, lost somewhere along the way. And then it’s her beloved, long-awaited daughter who goes, tipping the already precarious family balance into a mess of predictable men.

And how the established gospel of words meant that the fourth, empty place could never be properly filled, Halley thought, even if vivacious Norma had lived.

The hat trick. Halley teased it out, trying to tame the Medusa head of history; how to understand the trick with the hat. What did it mean?

Okay, so your ageing mother draws your baby daughter’s name from inside your wife’s smart hat.

Or, your hopeful mother-in-law pulls her puny granddaughter’s name from inside your empty hat.

Or, your aged grandmother finds your first name inside your mother’s old hat.

All of which are the same thing, it appears, the selfsame people and the very same cocked hat; the singular, unlikely name. Though the words make it seem impossible.

Halley knows about names. That some are more powerful than others, and that it isn’t always possible, or advisable, to name a thing as it’s commonly called, because this could mean trouble.

So he was never Daddy, but Your Father, and always with the slippery slope of italics. And because you were a girl, you had a koekie (and you must never smirk when offered a delicious, juicy koeksister). Children went for a tinkle, or did a jobbie, though grown-ups just went to the toilet without having to say, nothing about number one or number two. Except Nana, who always went to spend a penny, even at home, where you didn’t have to put the money in the slot. Also, you were to say excuse me if you made a poepiddy-poep. Which was a fart, though to say so was vulgar. And there was no need for even the silliness of willie in a family of females, forget about the other names, which were even worse words, and then no backchat you just had to eat soap.

But a name like Halley! This was a terrible punishment; plain stupid, really, and fit only for a complete ninny. So it didn’t fit her at all.

Halley had heard how in the birth register her father had meant to write ‘Hayley’ after Mills, but that he’d made a mess. For which he went on to blame his wife. Firstly, back when he’d admitted that the fresh-faced, girlish little blonde appealed to him, Nora wouldn’t leave off, always teasing and toying, harping on with words.

Hayley Mills! Oh really, she goaded her husband, And since when? So Miss Pollyanna appealed to you, did she? She what, Mr Murphy, pleaded with you? Said Kiss me, Mark, I beg you? And wouldn’t you just love that to be true, lover boy, another pretty one falling helpless into your arms!

After which brittle banter, words pulled this way and that, Mark didn’t know if he was coming or going, his brain in such a scrimmage from Nora and her sweet and sour tongue, her sharp, blunt mind.

And then secondly, about her name, Halley heard that Nora had often sung while doing chores, though what there was to sing about, her father said, buggered if he knew! In Nora’s repertoire, around the time of her first pregnancy, was the hit of the moment. Rock Around the Clock, by a certain Bill Halley and the Comets.

Oddly enough, she’d seen it spelt sometimes one ‘l’, Haley, and at other times two, Halley.

So who cared, you couldn’t hear in the song, trumped Mark. Or even know from the radio announcer’s voice.

But you could, Nora insisted, as only Nora could insist, attuning Mark’s ear, making him mindful of the consequence of spelling and pronunciation.

But these ephemera – words, spelling, enunciation, listening – he couldn’t grasp these, or not easily; they were enough to drive him mad.

So Halley’s name, whether one-legged or two, however it tripped or hobbled along: Well, people, it wasn’t his fault.

And certainly not hers.

Like many another child before her, Halley set out through this gnarled linguistic quagmire on a quest to find her real name, the one she was meant to have. She knew it was out there somewhere, if only her parents had looked hard enough, long enough. With enough dedication. Forget the happenstance of hats!

Even if they hadn’t had the energy to go out hunting after the one true name, how Halley wished they’d listened. That they’d just sat quietly in the lounge and waited for the sound. To enter. To fill the void. Because maybe it might have come, even to the corporation flats.

Mournfully, the spirited girl imagined her name as an intended, wandering around like a restless spectre, sad and searching. For her. A home in which to settle. When I’m calling youooo oo oo oo, oo oo oo. Like the song.

But what would it call her? Halley wondered anxiously. And if she didn’t know what she was being called, even that she was being called, how would she answer to her name?

At least Halley knew that her name would never be Ruth, because she, Halley Murphy, was merciless; or Arlette, which was too small and sheer and frilly to cover anything. And not Tammy, either, again because of that goody two-shoes actress. It was . . . possibly . . . Ursula. Not Ur-soo-la, but pronounced boldly: Urshla.

Urshla was suitably contradictory. A sexpot filmstar a virgin martyr a natural wild streak that could forage in the wilderness for food. Halley’s real name would come out of the water dripping, both sleek and shaggy, having caught a shining salmon with a single sweep of the paw. Sniff the air at night and find berries, and pinpoint the bear in the starry sky, standing in its naked fur, up on its hind legs, ready to face down the fierce hunters when they came close enough within its short-sighted range.

But hard as she tried, her real name didn’t come to her, and she couldn’t find a way to go to it, although she closed her eyes and concentrated, whispering with spirited devotion.

So she changed her mind.

Names! Oh, rubbish! Please, they were only things given. By and to and away. Which meant not only gifts, but germs, or old clothes. Unwanted attention. A thing called cup was near as nuts a mug, and ‘Halley’ was close enough to any other name you thought you might better deserve.

But if she was stuck with Halley because other people were already stuck on it, then her best recourse was creative recasting. To take her name out of the hat once again and re-configure it in a narrative of her choice. Inventively feathered or flashed, the wide brim dashingly turned, but with some plausible elements in order to persuade people of its truth.

So using the base facts of Mills, and Bill, and having looked for possible links under H in the compact encyclopaedia, she came up with the skelly story that her great-great-great she wasn’t sure how many generations but far back, way on her mother’s side, she was related to the world-famous astronomer Edmond Halley.

Ye-es! she nodded as she told, great news, wasn’t it, emphasising that the appropriate response would be awe. And when people looked at her blankly – her own father only snorted Edmond! – she prodded them further, bright, tenacious girl that she was.

The comet, you know?

Until it dawned on them, Oh. Yes. Halley’s Comet. Fancy that!

And she studied their faces, not convinced they looked suitably impressed. Whenever she could, though, she put it about that she was indirectly named after an incredible heavenly body. An exceptional phenomenon.

Listen, she said, Hal, emphasising the peculiar sound of her name, not Hay, like straw. It’s got a double ll, see.

Which to her meant like the comet, with a distinctive, remarkable streak.

And it did come to be a distinction, of a sort, even if the elliptical comet were to be visible but once in her lifetime, and then rather indistinctly, and though the times seemed barely to register, never mind take notice, when to the watchers there appeared a mackle of blurred printing across the southern skies.

No fabulous spectacle or great shakes. People had been warned to anticipate nothing much. But there it was regardless, Halley’s Comet.

And Halley Murphy found something comforting in the brief collective ken of faces turned skywards. She was happy to catch even the faintest glimpse, ever hoping, from the uncertainty of earth, to see as it is in heaven.