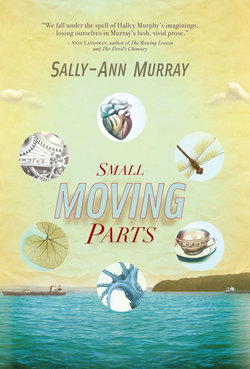

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Toothless cavity

ОглавлениеA few more weeks pass, and Nora is over the worst of it with the baby. No more crisis, somehow. She doesn’t know what it is. Maybe they’re just used to each other. Even their bad habits. The skinny thing gains, though it’s ounce by ounce, and it remains distressing to see her little body naked. Half starved, she looks; an awful rebuke to a mother.

And what with being so busy with the child, and going off to work, constantly reproducing her labour in order to live, Nora herself doesn’t want to eat. It’s like a reciprocal scientific law: as the baby picks up, the mother loses. Nora becomes nauseous, and the child less fretful.

Slowly, the infant fleshes out, her angles more padded, though there’s never a baby’s chub-cheeked bum, and the mother, well, she’s not yet skin and bone, but sure there’s not much for a husband to hold on to, were he home, and should this have been his desire. Though he might well not have wanted to, for such a body would have him running the gauntlet: the collarbones stick out, stark as a wooden coat hanger to beat him about the empty head.

Then, without warning, the mother feels fragments of grit in her mouth as she bites into her (single) slice of (dry) toast.

She spits and checks. It’s tooth. Hey. Would you believe it! When she goes over to the mirror, the glass confirms the feeling of her tongue. Cracked back molar.

Which is the beginning of the end.

By mid-morning, more than half of this tooth is broken off at the gum, and other teeth have begun to chip in thick, bizarre flakes, like scales. Yet others foliate around the silvery, mercuric fillings, which is but a precursor to the inevitable breaks.

Nora is very poorly, and deals with her baby daughter only as well as she’s able. It’s one of those situations where generous amounts of Woodward’s Celebrated Gripe Water are useful, administered by the capful, straight down the gaping throat. Gooi sommer net. Amazingly, the child does not hurl it up. She sleeps.

After this, it’s all Nora can manage to find something for her own pain. A swig comes in handy. And another. Though it’s only gripe water, and some paregoric, which is really for bad stomach, but it’s an opium tincture so it might help. Then one by one she crushes Disprins in a teaspoon, adds a few drops of clove oil and applies the burning paste to her gums, wadded over with strips of soggy cotton wool saturated in TCP. She tries every trick she knows, desperate to find an amalgam against her pain. She sniffs self-consciously, aware of . . . that strange smell. A dispensary. Herbal and hospital, the door of death, or healing.

Barely able to speak, her words thick and slurred like those of a common drunkard, she telephones the dentist and fixes an urgent appointment. Which unfortunately is Tuesday 8am, soonest, about two and some days away. Then she swallows a paper of Grandpa headache powder and tries to pass out past the pummelling and pulverising in her jaw.

She makes it through the rest of Saturday. On to Sunday. Monday first thing she calls the office to book off sick.

The rotten, metallic taste in her, the chafed tongue with nowhere to hide. Inside what ought to be her mouth, although she cannot stomach a close look, there opens a red cave of bloodied ice and bone as if some brute monster has been feeding on flesh. Her jaws snap to in horror. Trapped, she can feel how her inflamed red tongue lies in its pool like some flab of raw animal fat.

When Tuesday finally comes around, Nora takes the baby to the neighbour downstairs, as she always does on workdays, and the woman minds it along with her own two for a small sum. Then she walks down to the circle on Queen Mary and catches the City bus, holding a handkerchief discreetly to her mouth as she pays the fare, but removing it immediately afterwards in order to appear dignified as she faces the other passengers while trying to find a seat.

Every gear shift shudders in her head. The sheer lawn hanky may seem refined, but Nora needs it to disguise the swelling and take the bloodied spittle. And to conceal the smell of fouled blood which has begun to suffuse her person.

She has seen black women who come to town in quite smart clothes, but with slipped, vigilante doeks wrapped around their lower jaws and tied at the back of the head. Protecting their mouths from wind and germs, she’s surmised, since they have ‘the toothache’.

Today, nursing her mouth on the bus, for once she would like to be so regardless of self, so without self-consciousness, that she could claim in public the comfort of evident warmth against her ache, shamelessly revealing her distress. Though the fact of having to weigh up the idea shows her how impossible this would be. Even when she’s in agony, she agonises. She is much too mindful to forget herself; all she can think is that she’d really look a sight.

Then, thank heavens, without having to wait she is in the chair at Eagle Building, her stinking, odious suffering handed over to Dr van Toren.

Flinching, though faintly, evident only in a superficial flicker about the nostrils, the dentist leans in to consider what is left. Finds horrifying caries. Spalling. Corroded enamel perforated to pulp; parts fragile to powdery. Several teeth: dentine evident; molars – the grinding stones – themselves ground down to nothing, even disintegrated. Septic roots.

What is this? he frowns, suspecting. Then turns away from the patient to the steriliser in order to grimace to the eyebrows. It can be only prolonged vitamin and mineral deficiency; calcium, he thinks, over the frame of his glasses, the cloth mask. What else to explain this extreme oral pathology?

Nothing that will comfort this poor woman; a slight, elegant young lady wearing imitation pearls. She is in a worn, mint green pastel twinset and fawn pencil skirt, her slim, stockinged legs extended past his bent waist, feet enclosed, he has noticed, in classic two-tone pumps, scuffs polished out, but rather down at heel. Still, yes, most lovely; an effort to appear chic.

He pulls his mask down and in an engaging, broken English, repetition with variation allowing him pause to place the words he needs, he finds this not good, no, and for this he is sorry. Not before is he having seen such a terrible thing. Now please, he requests with an upturned palm, To rinse. Twice, he indicates, raising two fingers like a scout’s honour. And while she does, he scoots crabwise to the counter on his stool, and with his back turned, pens notes into a folder.

With each sip from the glass of pink liquid – discreetly sloosh, and spit – Nora avoids following the debris that swirls down the porcelain cavity.

Then Dr van Toren swivels around to face her, capping the pen. And for me, he continues, I must say to you. What also I am seeing here today, you (another beautiful, sophisticated gesture), this is a lovely lady. But, however, she is too thin. And I am asking why. This is my big question. What can be the reason? So if you would please to tell me: What is it, the food you are eating?

And then there is very little to say.

And so there is Nora, in her early twenties. And despite having been careful, she has a runty baby, a half-day clerical job (plus typing at home, addressing envelopes for various companies), a part-time husband, and not a tooth in her head. Single, whole or otherwise.

She is toothless. Which has to be some loss. More than any young woman might have expected, and certainly so much less than she had hoped for.

On bad days, Nora will become sarcastic, which is the closest she can get to humour. So much for the dream! A rocking chair, a cup of tea, a book and a baby. Forgot to include the husband, didn’t she. Took it for granted. And yes, the teeth. Now look at her. She gargoyles into the mirror. On worse days, as you may expect, she cries, unable to tolerate the sight of her slumped lips and flayed gums.

Nor was it possible, at that moment in the dental surgery, to appraise her face through the image of the dentist’s expression, the neat, considerate man who probed her sensitive mouth. Not only because he kept his emotions politely in check, or was man enough to deflect instances of imminent professional failure, but because she herself could not bear it. To look. See her degradation reflected.

In the chair, she focused on his name, worked in black satin stitch above the upper right-hand pocket of his white coat. Van Toren. What did his name mean? And why the need for the stitching? To identify him back in dental school? Kept, in his present practice, in case, distracted, he forgot who he was? Perhaps he was even accustomed to losing his coat, which again would make him forgetful. Perhaps it was merely a requirement of the dental profession; a rigorous, upfront code of ethics; a sign of the workmanship one might expect at his hands. Certainly, the stitches were extraordinarily precise. Machine embroidered, probably, otherwise an unusually dedicated wife.

Nora tries not to think of his hands, as they ebb and flow, away from her and back again. She studies his head, the dark, oily curls clustered above his forehead, giving his sallow skin a suggestion of youthfulness. He is maturely handsome, she sees, though scorns herself for such a conventional observation when she’s not remotely looking. The dentist leans back, pausing. Nora notices that in the left pocket is a black-and-silver Parker pen. Fountain. Capped. Still might leak. And a tiny penlight torch. Though off, unlit. Still, pen:light. They lie comfortably together.

Dr van Toren was thorough, but gentle. Thoroughly gentle. His pensive insight and compassion were offered lightly, without knowing regard for the authority he extended over the young woman in the tilted chair. He asked once, and did not probe further into Mrs Murphy’s unsatisfactory answer. His clinical enquiry was reasonable, and he hoped that she was too.

This left her both grateful and excruciatingly shamed. To be seen in such a debased condition by a person who saw her situation without her having said.

The only solution, understandably, was complete extraction. Of all the roots, and the shards of damaged crown and cusp which remained. Thirty-two. Nothing could be salvaged.

He tells her this. Against his wishes, and against her own best interests, he tells her more. He does this in the interests of expense, which he sadly appreciates is of more than passing interest to her.

For the procedure will cost substantially less if it is performed in his rooms, rather than under general anaesthetic at the day clinic in Durdoc Centre. And he means today, now, because she must know that this, what he has to do, what she must have done, it cannot wait.

The chair will also be more painful, yes, but since she has no choice, this is what she chooses. Afterwards, you see, there are still the dentures to consider, the cost of which will not be inconsiderable.

Dr van Toren spares his patient no details, refusing to pretend. He is not cruel, but neither will he deceive. For from what he can gather, studying his patient sympathetically, examining the damaged teeth, she has already been injured by complex deceits and denials, her own, even, and certainly those of others.

As always, the solution will be pain and money; both will be at her expense.

It was not unexpected, so Nora steels herself, consoles herself with nothing. What did she think a dentist could do? Save her? Save her teeth? Perform a miracle? That Dr van Toren, like some fantastical towenaar, could magic back that which had disappeared?

The questions burn like a dispassionate blowtorch as she cauterises her foolishness, making ready.

When he is done explaining, and has arranged, through the receptionist, to reschedule his appointments, have the neighbour look after the patient’s baby for the rest of the day, and for her place of employment to extend her sick leave, he proceeds.

Beginning with Novocaine injections, which are tolerable in the soft gum, but pierce her hard palate like inflexible wires, glowing red hot. When she is numbed, the man continues, tactful and courteous. However, he must lean over her and steady himself and grip fast and twist, using the resistance of the chair in order to do his work.

He cannot be clinical, for the action is not in the hands, merely, but the whole body. The torso strains in the manner of a labourer hauling a heavy machine. The feet and legs, too, although obscured from the knees down by the chair, cannot stand by indifferent to the whole business, as they are called upon to balance and counter-balance, rooting the dentist’s weight as if he were shirtless in an old-fashioned slaughterhouse among blood-stained workers, all in slippery aprons hoisting deadweight carcasses with hooks and chains that have been muscled over iron girders. So if the dentist is deft, he needs also to be strong. He is sweating. Heavily. Nora can smell him. It is far more than mere beads on the upper lip; his face is glistening, close enough for her to study the pores.

And so it proceeds, this extraordinary, deliberate violence. The specialist mechanics of the dentist. The crude instruments of medieval dentistry known as the pelican and the turnkey lying behind the gleaming modernity of stainless steel.

Because what happens, after all, is this. He makes her comfortable, after a fashion, then cuts a long, deep incision into the gums, the full curved length of her lower jaw. Using a fleam, the tissue is split into two pink, parallel labia, and one of these flanked, fissile leaves he peels back left, the other is levered right, and both are pinioned with the clips and cotton wool wads passed by his assistant. A tubular drain is clamped in the crease of the patient’s mouth, sucking away the copious liquids which rise and pool.

Using such rudimentary devices as a metal probe and varieties of grasping forceps, following the fragmented peaks and troughs of the stumps and the shadowy, submerged outlines of the X-rays, Dr van Toren locates the furthest reach of each root canal and with pliers and drill, individually extricates, eradicates, what remains of Nora Murphy’s teeth. And you would be surprised at how much this is. For although the upper biting surfaces, in the main, are pulverised and crumbled, many roots are deeply embedded, since that is the purpose and definition of a dental root. To hold fast. To fasten firmly to the jaw. Not to be pulled out.

Given the state of Nora’s mouth, though, some teeth pull loose with relative ease; others are compacted, and must be forced.

The procedure is repeated for the upper jaw, with all the added complications of angle and approach.

Throughout, Dr van Toren must move in as closely as possible. He must do everything but straddle. He must yank and prise, wrestling with Mrs Murphy’s arched resistance while trying not to hurt her and hurting her all the same.

Throughout, though she may shut her eyes, despite their involuntary tendency to remain open in sympathetic horror, she has to keep her mouth agape, more so than the very mask of tragedy. The young female nurse is breathing heavily. When she is not cued to pass surgical tools from the tray, she holds the patient’s hand, stroking stroking soothing with her feeble, frantic thumb.

Nora is the patient, so it is up to her to be patient. Van Toren is the doctor, so he must doctor her. And there is the nurse assistant, who must nurse and assist.

For all three people in the room, over the course of several hours, the actions required are condensed to the most simple. Lie still open wide grip twist pass stroke pull. By the end, patient, doctor, nurse, all are reddened with blood.

And then it is over. Nora has found the wherewithal to endure.

There is no one to fetch her home, unfortunately, so again Nora weighs her options, and it’s the bus. Though sweet Jesus there’s a seat so she doesn’t have to stand and it’s the 86, not the Number 7, so she can get off right outside the gate, instead of having to walk up the hill from the tearoom.

With all the bruising, she looks a wreck, and for a while some neighbours suspect that Mark’s back on the scene, because Nora’s been beaten up.

Then after a few weeks the purple and blue fade to marbled olive, seeping to dull yellow. And then one day Nora looks nearly normal again. Her mouth is healed.

Dr van Toren takes the wax impression of the patient’s gums, and the dentures are fabricated to specification by the technician, methodically honed and buffed. Minor adjustments of tooth height and bite are made in the dentist’s surgery during Nora’s next appointment and, There. The teeth fit, as well as can be expected. Fixed up. The teeth become her.

Again, Nora looks like herself, comely, a ready smile with thirty-two serviceable teeth. Her full complement. Not snow white, which wouldn’t be credible, but reassuringly milky, just this side of cream. They are moulded of polymethyl methacrylate, a specialist acrylic plastic. Of course there is rubbing and discomfort, most of which diminishes as the gums harden, becoming accustomed to the new addition, though a few raw, ulcerated spots remain for always. And always the odd, clicking sensation of something extra, of talking with your mouth full.

In addition, she must become particularly vigilant about what she eats, which is quite a turn-up for the books, given that she’s spent her life watching out for food. How to get it. Enough of it.

But on the whole, she is, as they say, right as rain, though when she considers the pink, still toothless mouth of the baby, then she really wants to spit. And when she’s starting to forget, busy again with the inviting blankness of her crosswords, Nora chances on the word ‘prosthesis’. Reads 1. (Gram.) Addition of letter or syllable at beginning of word e.g. be- in beloved. 2. (Surg.) Making up of deficiencies (e.g. by false teeth or artificial limb). Part thus supplied. And she feels so stupid that a damn dictionary can make her cry, reduce her to tears. She cries and cries.

Every night, the young woman must remove her teeth like an old person and soak them in a sterilising solution, though never will she tolerate the glass on the bedside cabinet, the false teeth steeping, sleeping, next to her bed. Come bedtime, the teeth in their glass are banished to the medicine cabinet.

But despite this little, off-putting distance, and the lifelong fact that every morning she starts the day smelling like the chlorinated public swimming pool, her taste buds cringing, gradually she comes to accept.

Okay, for pity’s sake! The teeth are mine, all right, they are part of me.

Still, for some years she will try to hide the fact of the dentures from her small children, because she realises that they, like her, will be afraid of the person with the shrunken face. Yet with time the teeth become a familiar presence, even to the little girls. Their mom’s falsies. Like the cotton wool padding some women stick in their bras to give them bigger boosies. Over the years, the teeth become their mother’s, and it is only in wearing them that she is their mother and, to herself, a woman as becoming as once she was. Only people who know, know.