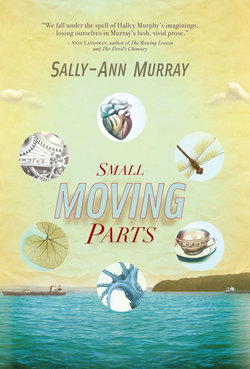

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Intimations

ОглавлениеYou always asked your mother about what came first. What was before. And she told you some, but always with such exaggeration that you knew she was leaving big gaps.

The story started with sand, she said, though you thought that unlikely.But that’s the start of a diamond, she explained, so then you listened.

Because how fun it was to imagine a scene where you were a child in the olden days before the Big Hole was so big and empty and when everything was still possible without complicated machinery and maybe you were just walking down the dirt road as usual and you stubbed your toe on a rock and when you looked down there it was a diamond in the rough the biggest diamond the world had ever seen and you were famous and you made your family so rich that your mother didn’t ever have to work again and you gave some to the poor children because that was the right thing to do.

Though your mother’s diamond story is first about beach sand and how people never think of it, or if they do, they think it’s just always there. Constant, she murmurs as if it means something, constantly there.

Halley listens. Hears how the sand she saw just yesterday is never the sand she might see tomorrow; not exactly. How sands can shift.

So if we sat over there, last time at the beach, near the trampolines? Nora reminds her, the stripy towel spread over the soft golden sand . . .

Well, twice a day the tide turned, making that sand afresh, churning and dredging, mixing it all up. Sand is always on the move, says Nora, shiftless, and there’s no guarantee that a beach is forever.

Where you sat, it could be scooped away, hurled into a hull of exposed rock. And only a fool would deny the force of water on brick and concrete when the twisted remains of a pier are exposed on a gutted, concave beach.

It was very difficult to understand her mother’s tale when everything was only sand and rock and water. Jen was sleepily bored, which Halley supposed did serve the purpose of a bedtime story, but Halley waited for people to arrive in the picture, which would make it more interesting. That’s where a story really started, she believed; the rest was just setting the scene.

Once upon a time, Nora began, There was a boy from a poor family. She looked across at Halley and Jen, all playful.

Not only was he poor, worse, he was unlucky. In love, and generally. He had half a mind to call it quits and light out to sea, never to return.

Poor, poor chap, she played the line, larking about in language, For all we know, he had bad breath, two left feet, was all thumbs and not much else. The works.

Yet he was a nice young man, their mother continued, And deserving of more than he’d been given. One evening at dusk, the lovelorn youth was mooning along the Golden Mile wondering how he could come upon the money to marry his girlfriend, who of course was expecting.

Although the lad was stout of heart, he found himself close to tears at the narrow range of options that presented themselves, which was exactly none. When wragtig! his eyes spied a faint gleam. Was it . . . ? It was not a glinting bottle top embedded in the sand, but a ring, and in the glow of the lamplight it shone and beckoned like a fallen star.

Ay yai yai yai! Nora exclaimed.

Si si señora! Halley sang in refrain, happy to have her mother acting up.

Now this was a lucky strike, and the youth knew it. He was smart enough and enough in love to know exactly what to do. On foot, despite the distance and the late hour, he covered the miles, made his way straight to the home of his lady love. Her parents’ house. Rapped sharply on the door with his special knock – nok, nokkie nok nok – and when it opened said Good evening and Very sorry, Sir to her father, but a man’s gotta do, and when he saw his sleepy lovey even in her old dressing gown and rag curlers come looking over her father’s grumpy shoulder, he went down on his one knee, holding out his glinting, sparkling, magical finger.

He begged her to love him, to have him, as he loved and would have her.

Had had her. Had she been had? Would she be had?

Halley’s mind was reeling at her mother’s spinning tongue, all these confusing possibilities cast out upon the waters.

The suitor offered the ring as evidence. Of his true love, her mother said, her eyebrows twitching, because what else could it be?

And the ring worked. It wove its enchanting spell and the girl was persuaded, imagined that she saw in the unbroken circle the very hold of undying love.

Though she wasn’t actually that much of a romantic, Nora tossed in. Life had taught her to be realistic, and in the jeweller’s scale she’d weighed up in her mind – Nora’s fingers delicately indicating the minute balance – against her big belly – hands round and full – against the leaky heart – palms sweeping away – against the pressure of the times – fingers clawed into a clutch – the suit of her suitor.

And so because it suited her, she said Yes. That’s all she said, and that was all it took. Meaning I do.

Something like love and luck, my darling, said Nora to her fascinated little girl, tucking the blanket in, and patting the other, sleeping child, these were held in a ring that the couple liked to think was magic, though they did not rely on this obliging circle to provide the happily ever after. Not them. It was only a ring, after all, not a genie.

So you want something? Nora said they would one day ask their children, You want something big and you want it badly enough, the only hope is you must go out and make it happen for yourselves.

The end, said Halley, sighing back a laugh as her mother turned out the light.

So somewhere in all these stories, you come to believe, in what’s left of the coastal bush near Addington Beach, lies what was left of your mother’s love even before she went on to marry Your Father, the man who’d given it to her. The love. If that’s what he gave her.

He’d bound her with the obligatory ring, of course, a diamond flung towards the sea as she sobbed. There, vat terug. Have it! I won’t do it. I won’t take you back.

This was what she felt about her unsteady engagement to Mark.

The stone was small, true, but in the circumstances this meant real. A raised jewel in a solitaire setting. It stood proud, not only to make the most of the modest stone, but as a declaration of Mark’s love, his grown-up pride in the promise of firm commitment.

That ring cost him plenty pounds, which was dear when you considered his weekly envelope. She knew the exact cost, in fact, because he’d hurled that back at her in a rage after she’d twisted the ring from her engagement finger and thrown the narrow band across the dunes.

He’d paid the ring off as men of his kind did, but even this discipline was remarkable for a man like him, and with the ring vanished, his broken heart saw weeks of hard work gone to waste.

When she throws the ring, the stands of strelitzia and milkwood along this part of the beachfront are themselves already intermittent, broken up by hotels and parking areas and rickshaw roads. But even the remnant undergrowth remains dense; you try finding a ring in that lot. Gone forever as far as she’s concerned.

Not that she goes back to search, mind. That would be fruitless, not to mention humiliating.

So it’s just gone. Overs.

Soon, the ring is probably buried, that being the nature of sand. Tons of it, and constantly shifting. Swept by waves into dunes; tumbled and banked by undertows. We can be fools, can’t we, for love? Deluded. The whole obscure machinery coming in to play alongside the regular dredging of the notorious sandbar across the harbour mouth, countering littoral drift.

So the ring may not, after all, be buried forever. May not have been buried for even that long. Might have been spewed up by the trailing suction-hopper dredger near Tramps or Vetch’s and some lucky bastard found it with a metal detector, and sold it at Hard Times Pawn down Point Road. Which means, perhaps, that once upon a time, for real, the ring might come to encircle someone else’s dreams. And if nothing else, it makes a lovely story.

Unbeknown to Mark, his mother had intervened with his fiancée to patch things up through a series of handwritten pleas, letters scripted in a deliberate, upright hand.

Following the curves of Felicity’s copperplate, oddly pleased to hold the power of this rock, paper, scissors in her hand, Nora thought of iron, steel, tin . . . brass, nickel . . . some other clever alloy, anything solid that would allow love to prove its mysterious mettle.

And so there came the day that Mark and Nora were married. Not that it made any difference. Because then there were all the days that came after.

Dates have their significance for family and forensics. Yet figures are seldom the acid test of the individual. Number-crunching crunches; the cogs in the vast machinery grind. That, Halley would happily inform you – if she’s not in the spiteful mood of mine to know and yours to find out – is why rust resembles dried blood.

So yes, it was early 1960, and a child was conceived in the after-shadow of Sharpeville. Tumbled in the wake of the flood, the turn of the rising tide.

Deep and wide, they sing in church, Deep and wide, There’s a fountain flowing deep and wide. Plunge right in, Cleanse my sins, There’s a fountain flowing deep and wide.

Sharpeville, she later supposes, is one conceivable marker, though it glanced past some windows unnoticed, misapprehended by those who took it for a passing effect of weather, an inland pressure front curving towards the coast.

Passes and permits, the black leadership declared, These are their water pipe, and we will close it off.

Or as Nora read in a cutting from The Star that her sister Agnes mailed with a letter from Vanderbijlpark: ‘Police open fire under a hail of stones’. The opening volley of a gathering storm; a mourning tent of darkened sky thrown over the early Sixties, pegged to the ground with tense, booming wires against the winds of change.

Though Halley’s conception, really, was predictably prosaic. The father (not yet hers, after all) was on the razz, thrusting blindly, bluntly, in riotous conjuncture. The mother (similarly no relation) might be imagined more quietly, much less simply, as wanting to make from this some love.

Love me, she urged.

I am, he grunted.

Possibly, she lay back looking over Mark’s solid shoulder, her gaze tracing the blotched water marks on the ceiling, drawing their indistinctions into . . . amoebae, clouds, group areas, crosswords, galaxies, paper dress patterns, my goodness, a foetus!

When it came to marriage, theirs was more a shot in the dark than made in heaven, and to establish the State of the Union, it’s important to understand that Mark Murphy liked Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, a blaring, razzling trumpet brash enough to blast the rainy-day blues into the shine of the good time; he was keen on Sophiatown music, Charlton Heston, Charles Bronson. Brigitte Bardot. His brand was Texan Plain, a pack a day. His aftershave, Old Spice.

And Nora Hoare? She liked Bing Crosby, Perry Como and Ransom 20 Special Filter Mild. Made a box of twenty last a week, meaning Monday to Sunday, the full seven days. She found Dick van Dyck a laugh a minute, and both the Hepburns were gorgeous, in their different ways. She loved Hey, there, Georgie girl, and her scent was 4711, or Chanel No 5 as an extravagant gift. And if you were bringing chocolates, please: make it Cadbury’s Milk Tray, not Black Magic, which was soft-centred pastel fondant, the chocolate too dark. And when it came to flowers: glads, definitely, best you didn’t even consider tacky carnations.

Of course these are over-simplifications, a list invariably listing and leaving out, close-fisted against the indignant exclusions which are beating at the door, unable to see eye to eye.

So, if you like, add that both Mark and Nora had a thing for Frank Sinatra’s crooning; that they loved to sing, and really could. That he played with a band called The Metronomes, and when he wasn’t blowing the sax or doing a Lemmy Mabaso kwela on the penny whistle, he had a soft spot for the bottle while she barely touched a drop and sang solo with the ensemble choir at Manning Road Methodist.

Seeing her there, for the first time, he thought he’d met an angel, he told people later, pausing for effect before playing the fool, explaining that it didn’t take him long to come down to earth.

There were the newlyweds, settling into a flat near Tollgate Bridge on Durban’s Berea. In April 1960, had they looked outside themselves, behind them or in front, there would have been the day they could see a huge black cloud crowd moving marching making its way towards the city centre from the depths of Cato Manor, swelling closer and closer from over the ridge and far away, more than enough menace for an anxious population to consider a horde.

Figures in classic khaki gardeners’ outfits and floppy hats; kitchen boys in white shorts suits edged with red braid; factory workers in overalls hanging loose over worn, stretched singlets. Other protesters wear nothing but long, long-sleeved shirts, as if they have freshly fallen from an old-fashioned bed. There are some in checkered twill clerks’ trousers, the peaked cloth caps of delivery boys. Yet others go sweatily bare-chested and might be naked for all it can be determined, their bodies concealed below the waist by the density of the crowd. Among the throng are women, too. Some in house-girls’ dustcoats; in office skirts and blouses; in full, circle skirts sashed at the waist. Women in mismatched, make-do tops, or with lengths of printed fabric wound beneath the arms, a bulky knot holding the drape together across the breasts.

Hundreds of blacks. Thousands. Workers, the unemployed, rough-shod individuals and some studying correspondence, all determined to be people. Some men have sticks in hand, some – Jesus, are those pangas? as they churn through the whites’ green suburbs, having broken the police line. The mass picks up form and movement on the way, swelling into a collective that includes black men in jackets and snappily pressed slacks, women in flared coats over smart frocks, a cluster of difference that slowly morphs into a single, fluid body, surging towards the Durban Central Gaol to demand the release of political prisoners.

Yet even had Mark and Nora seen the crowd, or heard the strident voices, would they have understood, noticed the little leaves gathering force on a growing stream? Liliesleaf was one thing, but they both laughed at the joke about how the natives were revolting. For Nora, okay, so black people worked hard and got a raw deal, but as her husband said, wasn’t that because basically they were (not to be blunt or anything) still so bladdy bush, more or less raw themselves? And if there were pass laws, he explained, you knew they were there, like all laws, for a reason. It was logical. A ruling party had to rule, otherwise it was only a party, and things would get out of hand.

Hell, but Mark knew how to make a person laugh! When she thought quietly, Mark’s gregarious buzz absent from her head, even then the best Nora could do was a pretty tight tautology: Wouldn’t things improve as they improved, meaning black people and things, if they could only be more patient?

So perhaps the Murphys succumbed to the belief that history was only a way of time passing. Passing time. Time came and went, the days rolling around and away, but history was theirs, wasn’t it, because people like them were the ones who were making history happen.

And of the knot in the stomach, the thorn in the sole, oh what is that sound that so fills the ear . . . ? Perhaps they preferred to know nothing, indifferent to the growing body except for Mark’s pleasure in his beautiful darling, and she with the joy of his six-pack voice so resonant upon his flat, firm belly.

Reasonable rent and convenient location aside, the couple had chosen their flat because of the small enclosed balcony which jutted towards the distant water across the leafy canopy of the Berea. Though because of the buildings in front of the block, and the hilly slope beginning its slide down the back of the Ridge into the tangled subtropical bush, you couldn’t properly see the sea. Not unless you went onto the balcony and craned your neck, tilting the balance in order to catch a glimpse of the city’s one certainty, the constantly changeable water.

Before her birth, Halley had sensed the sea, floating in her watery sac, felt the beacon tug a body when the woman ought to have been indoors, making ready. But Nora was always on the balcony look-out, hoping to find the foetus’s father.

Oh, she’d found her man and they were married, but now she needed to know where he was. Was there a device for this, Nora wondered silently, something similar to a fish finder? She’d give her eyeteeth for such a convenience, but nope, not that she’d heard. And actually, who’d have the resources to waste on tracking down a wanderer like Mark? It made no sense to throw good money after bad, and when he didn’t give a continental about being found.

Some mornings, with the wind cutting off the sea, slicing sharply through the centre of town up to where they lived for those short months, the air was brisk with salt. The wind blew in through the open window, whipping the lace curtain, blurring the glass where Nora stood, drawing hearts and arrowing them with a cynical, dismissive finger. The wind stung her eyes, left faint, crusted traces on her cheeks. Made her sniff.

Endless blasted wind, she sighed, repeatedly washing the windows with water and vinegar, buffing a shine using the week’s old news, keeping at it until the glass was clear. Never crying, not exactly. Not Nora. Though there were reasons aplenty for tears.

Where was he this time, her husband? There was no one to ask. She was new to Durban from Bloem, without family, and the only friends she had were his, men who covered his tracks with sleek or tumbled stories, and lied to her face.

How Durban people laughed when Nora said she was from Bloemfontein, the very thought of it! They looked down on her, and mocked openly with calls of Vrystaat! Shame, they said, Flower Fountain! And obviously thinking volkspele, outydse tiekiedraai and vastrap to some fat oom’s piano accordion.

And she had nothing to counter them. What could she say, must she declare proudly that Bloemfontein was the most centrally positioned city in the whole of South Africa, so that if you lived there your life was equally close to every opportunity? That Bloemfontein had elegant culture such as these coastal types could not imagine?

No, she wasn’t stupid by a long shot, so she kept her mouth shut, knowing what a laugh this defence would raise among all the tanned, comfortable carousers, confident of their important lives in the country’s premier holiday destination.

Nora felt nostalgic about Bloem, the peaceful, orderly city of her youth. Tough times, she certainly wouldn’t deny, very, but still her old familiar. The smart, handsome boys from Grey College, walking past St Faith’s, their eyes politely averted, but clearly wondering whether; the uppity girls from Eunice. Summertimes, free to feast on a glut of fallen fruit. And once she was free herself, out of the home, Sundays after church, piekniek at Maselspoort, the willows swaying. And long evenings looking over the rooftops from Naval Hill with Roger, her sweetheart, swept off her feet with love but also thinking about the silliness of names.

Naval Hill! With not a ship in sight, only the old British naval guns mounted on the crest. The sign on the flat-topped kopje which announced that Here Lord Roberts had stationed his Boer War regiment, and the accompanying naval brigade.

All that skill lubbered uselessly inland! Nora smiled to herself, Roger’s arm around her cool, uncertain shoulders.

Sometimes she wore him like a heavy overcoat, she knew, but it was often chilly up this part of the country, and bitterly cold in winter. So she had to have something.

On Naval Hill, the air clear as pure atmosphere, there was also the university observatory. A huge dome like a cranium centrally cleft by a precise, expert axe. And inside the eyeball, though you couldn’t see, was an enormous, powerful telescope trained upon the skies, gathering celestial information. Just knowing that the telescope was there made Nora want to do something crazy, like wish upon a childish star and keep it secret in the hope of luck.

Which wasn’t like her. She had no time for the magazine frippery of horoscopes and star signs. I ask you, she would have said, and What next! Though she was a Libra, that much leeway she was willing to grant, and Roger a Pisces. You had to know, since people asked.

But the telescope had caught her imagination, enclosed and protected in its scientific skull, and she’d wondered, looking up at the building from where she stood, whether astronomy could chart a future. Whether its earthly eye might help a person to see where she was in the world and where she was going, beyond where she’d already been.

When she’d learned of her pregnancy, and once she and Mark had reconciled and gone hunting for a place to stay, she’d thought of the balcony as a pleasant spot for a nursery.

Here, she could nurse the child, once it came, she’d thought, seeing herself settled into a rocking chair, with a cup of tea, a book. And a likkle baybee.

Though Mark put paid to all that. Her husband was even then stretching his neck in an impossible straining to catch a glimpse of the harbour glowing at night. That was the problem with the sea. It was alluring. In some shapes it promised change, in others constancy. It could be the force that brought you, or carried you away. Whichever one you wanted, assuming that you knew what made you happy.

She knew about the grass always being greener, but sailors afflicted by calenture envisage the seas as green fields, she thought bitterly. Who knows but that men stranded on land might manifest an inversion of the same tropical delirium.

Who can say what Mark was after? Though he was not, judging by the past, a man in a hurry to settle.

He’d bunked all the time from technical high the year he’d started, preferring to hang around at home taking pot shots at people’s closely guarded laying hens. Once, the head clean off a prize rooster. Fishing belly-up with home-made bombs, the used tins packed with dynamite nicked from a nearby factory and lobbed into the harbour. Wheeling and dealing with the Indian fellows by the Clairwood betting shop.

The last escapade, police had collared the boy way down the South Coast where he was following the sardine run and pinching what he could to manage. But they’d only hauled him back to his mother, treating the jaunt as the madcap jape of a miscreant male minor.

Not his mother, though. She’d well and truly thrashed him. There being no man to do a job that evidently needed to be done, she hadn’t held off, and while Mark had earned his fierce stripes, he still refused to go back to the books afterwards, since he hadn’t been at them in the first place. Life happened outside books, so why give a feck about flunking?

Fine, his mother had said, Forget school. Leave it for good, though god knows what good will come of it. But don’t think you’re going to sit around the house all day soaking up the sun, my friend. I’ve had enough with useless men. You’ll learn a trade. I haven’t raised you to be a good-for-nothing.

So Felicity Murphy had searched around and pulled some strings, people she knew who’d once known her convivial husband, places likely to take a high-spirited, independent-minded boy, if that’s how they could be persuaded to see it.

And so Mark was launched into the whaling business on the Bluff as an apprentice fitter and turner. For three years he learnt how to make machine parts and to repair engines. But not only in Durban, my china, more often on the move, sailing with the merchant marine far across the open seas.