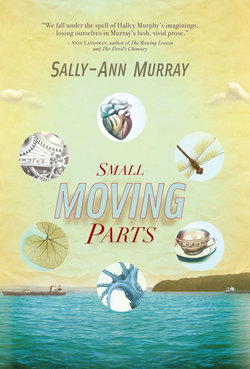

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mobility

ОглавлениеFor Halley, these may be flats, with flat roofs, but Kenneth Gardens is never a flat surface. Okay, she thinks, so yes, if they were seen from high above. But for the tenants this is never, though Halley is always trying to figure out how to climb onto the forbidden roof parapet so she can see down, like a bird, and maybe fly. How would you know unless you try?

For now, though, she’s obliged to live from the ground up, which is an altogether more complicated kind of complex.

At Kenneth Gardens each block has its own main entrance, a single doorless opening into a squat, curved tower. Except for Ixia Court, which has a functional, straight-roofed entrance hall. Halley believes that this is the only block with such a mediocre distinction, and it troubles her, because she likes the surprising accomplishment of the other buildings’ curves, the hint of superfluous style and refinement. The beautiful fullness which swells the access to every block except the one in which they live, where the blunt, straight line rules supreme.

Unfair! And of all places, she thinks, it is the entrance to their block which ought to be rounded, because their family is only females. There’s her mother, and Jen, and Halley. Which altogether makes 3.

Mommy sleeps in the main bedroom, you and your sister in the other one, and there’s a small enclosed porch off the back just for breathing space.

There is no substantial difference, in truth, between the block in which the Murphys live and all the rest. Whether the entrance is curved or straight, any pretence at flourish falls away as soon as you walk into the poky entrance hall, take two steps and come smack bang face to face with three rows of gaping wooden postboxes. Six, triple-stacked: 1 2. 3 4. 5 6.

Whichever block you live in, then, Ixia or Arum, Watsonia or Jasmine, any of the others . . . in all of them your options are limited. You can go up the stairs: on each floor there are two flats, shouldered side by side. Or, if you don’t want to head in, you can turn around and leave, wondering where to go. Or you can forget about what your mother has taught you concerning not messing with people’s private things, and climb into a postbox of your choice. If you could.

Since you can’t, using the matches you’ve stolen from your mother’s bag, or if those are finished the plain old sun forced to an excruciating focus with your pocket magnifying glass, you set alight the bundle of dry leaves and newspaper that you’ve wrapped around your own stinking shit and stuff it into the postbox marked Number 5. And then you scarper, run like crazy and leave people to think it’s the fault of the neighbourhood hooligans. Who of course are boys.

Because you are never naughty. You try not to be naughty. You are good. You try hard to be good. Though you do not yet understand that the existence of love presupposes that damage has been done. People may not know it, but love is a compensation; it must make up for what has been lost.

From the back porch, Ixia Court overlooks Walton Place, which is a short side street. Most of the other flats lie along Queen Mary Avenue, which is very long. If she goes out to the narrow front balcony, shared by all the tenants, Halley imagines she can see everything that’s happening on the avenue.

In the middle of Queen Mary are wide traffic islands, planted with trees. The exotic triumphal march begins way down the bottom in Congella with tall, waving palms, the long trunks thicker than elephants’ legs. Then it’s on to a broad-canopied stand of orange flamboyants, and then delicate pink camel’s foot near the Murphys’ block. After, the pattern almost repeats, but as if it can’t quite remember what it’s supposed to be doing, and then gradually it gives up, disappearing into tall grass and grow what may. But even once the islands end, the avenue continues in an absent-minded way, winding over the hill, up down up, until with some relief it arrives at The University. Here, it is delighted to be reconciled so unexpectedly with King George, and the two, well met, proudly survey the Jubilee Gardens.

Back down the slopes, even the Murphys’ end of Queen Mary would be quite scenic if the men from the flats didn’t use the shady islands as a parking lot and a convenient place to wash and fix their cars. Come weekend, rags, beers, radios and soapy buckets are hauled over from the flats; jumper cables, spanners, the works, are jumbled noisily out of gaping boots. You can’t go barefoot among this tinkering, because the men empty ashtrays and other rubbish on the grass. There’s lots of stompies and crushed papers and spark plugs. Gnarled wire, broken glass. So it’s not at all regal, despite Queen Mary.

And except for Mary, who was obviously a queen, the people after whom the roads have been named are strangers to the tenants of the flats. Nobody can tell Halley about Walton, who is their side street. Or the mysterious Kenneth of Kenneth Gardens, who maybe once owned this whole place when it was really a garden.

Most people don’t seem to care about the anonymity of the names. A road’s a road. The street is just your address, and while it would be nice to live somewhere better, here’s not always so bad.

Nora tells her eldest that whatever it’s called, a road is mainly a way of getting somewhere. From A to B, as people are fond of saying, Nora laughs.

Which Halley doesn’t reckon is really that far, if you look around.

For the children in the flats, what matters most is that you walk half-road down Queen Mary to get to the tearoom, where sometimes you have money for sweets. A sucker. Chappies. Nigger balls. Creamy toffees.

But money aside, for Halley and Jennie there are particular complications, as their mother has decided that her daughters’ singular directional arrow is up.

So they are the only children they know from the flats who are enrolled in a school called Convent High, on the prominent hill at the height of Queen Mary, the crown upon her majestic head. It’s a high school and primary school both, so the adjective ‘high’ means elevated, and perhaps refers also to the panoramic vista over Durban. Indeed, given that the institution is run by the Sisters of the Holy Family, it may also be intended as an invocation to raise the eyes upwards in spiritual aspiration, the dutiful desire of clumpy clay to be transformed into heavenly bliss.

This upwards distinction in the lives of the little Murphys continues an earlier precedent, when they were sent to Davaar Kindergarten, a progressive infant establishment run by two Swiss-German sisters, the Misses Zwinckel.

Kinder Garten: Kenneth Gardens. Perhaps Nora found the sounds pleasing, relished a certain balance in the euphony. Certainly, she knew from excellent repute that the school offered a caring home from home and a sound educational grounding. Both of which, of course, she’d already been working on herself.

People had snorted, called her a hard taskmaster for showing and sounding a boxed series of phonic flash cards to her first-born when she was but a speechless infant. But by the age of two, though still a spindling, Halley Murphy was able to read. The proof of the pudding, Nora knew, lay in the eating. Not that she had much taste for it herself.

In order to secure a place for Halley and then later Jennie at Davaar, their mother put her pride in her pocket and requested special fee arrangements, and having heard her account, the refined foreign ladies were happy to accommodate, given the woman’s evident respectability and her selfless efforts to rise above unfortunate circumstances. Thus are the little girls enrolled in their diurnal round.

There they are then, four, and three. Halley and Jennie in their vanilla pinafores buttoned at the shoulder, the scalloped skirts finished in royal blue satin stitch. The girls’ faces are shielded by broad white panamas, and each child clutches a blue cardboard suitcase stencilled in white with her name. Halley Murphy. Jeanné Murphy.

Nora puts the children on the corporation bus every morning, their season tickets looped in clear plastic luggage tags around the suitcase handles. Each time, she arranges with the driver about where to stop, although Halley knows perfectly well since she’s already been doing this for several months by herself. Like her mother, she has a good sense of direction.

When nursery school is over at midday, the sisters know to wait outside until the Umbilo Number 7 bus comes and then they get on and go all all all the way until the driver stops at the tearoom on Queen Mary, and then they get off together and walk home.

The slightly bigger girl, baby blonde hair turning to brown under her hat, she likes to hurry since there is always still so much to do. And she chides her slowpoke sister, who dawdles, swings her hat by its elastic like an Easter-egg basket, tries to twirl it on her finger, the sun glinting upon her dark, shiny curls.

For the rest of the afternoon, they play with their friends until their mother comes back from work. Which could be soon after two, if she can do half-day, or later, if not. All depending.

During which time, the girls shift for themselves, Halley keeping an eye on Jen.

The world just beyond Kenneth Gardens is very familiar. About midway along, for instance, Queen Mary Avenue is punctuated by a traffic circle. Not a full stop, but a poetic navel.

Halley loves the pleasing shape of the circle, and within it the bold black-on-yellow chevron that signals a sharp curve. She takes the circle as a centre from which her life, like that of others, has begun slowly to emerge. Along its axes there radiate a church, an Afrikaans school, a huddle of small, family-owned shops, the corporation flats and the intersecting roads. And don’t forget the bus stops, one opposite each of the circle’s grassy quadrants.

The bus routes are the lines which extend the world, promising ever greater distances. But in fact, buses aside, it is possible to walk miles and miles in any direction. The sky, as it still remains, is up, thinks Halley; the earth is down. Or on, in, under.

And walk they do, this female family. From Umbilo to what seems almost everywhere. Sometimes, the walking is leisurely, and there’s time to find small pleasures – pausing, picking up, pointing out. More often, they walk with determined purpose, because the mother has said they are going somewhere.

If you don’t walk, she says, With your own two feet, you aren’t going anywhere. That’s it. There’s not always money for the bus, so if feet are what you’ve got, feet are what you use.

Even when Nora’s flush, there are hard choices: the bus both ways, or just one trip and an ice cream? Which will it be, girls? You decide. And so their mouths are sticky with the short-lived memory, and their legs are very tired.

So they walk the streets. Pound the pavements. Discovering the city all the way, Halley thinks, from A to Z.

They walk in shine, and in wet, once even allowed to slosh barefoot in the raging gutters, just for fun. Singing in the rain.

What’s a gutter, girls, but the edge of the pavement, laughed their mother, twirling her umbrella.

On the way to Mitchell Park are houses like the town museum, with big grounds, and cars which live in garages. Closer this side, when they go to the Botanic Gardens, is Warwick Avenue, the houses stuck together half and half with people from different walks of life.

Some brown boys have got this kitten. Mushy grey, with blackish stripes. They’ve tied a tin can to its tail. The mewing is pitiful. The frail, gummy face and small jaws. The boys laugh.

You want? Have it!

You do want it. You really, really do.

But your mother says No, and drags you away.

Pets are not allowed in the flats, but you’d do anything to keep that kitten. Instead, the three of you must keep walking home, all three angry. You are full of hatred for your mean, heartless mother. And, for once, your horrible, stubborn sister is cried out with begging.

But your mother just carries on walking. She walks and walks, as though she is struggling to come free of an invisible cord.

Some days the walking is good, and you can feel it strongly, right in your body. Because while your feet are going, covering the ground at what feels like ten to the dozen, whatever that really is, you also set your shoulders straight and keep your head up and your arms stepping out briskly so that the oxygen can do its work, pumped from your lungs to all the far-flung corners of your body.

So you’re exhausted, but also filled with energy. You want to run, just for the hell of it, and sing out loud, even shout!

You do sing, all sorts. And you run, running ahead. Sometimes, your mother and your sister seem so very far behind.

And yes, you know you look ridiculous, perfecting a new run, jumping and knocking your heels together, and that all this racket is disturbing the peace. But you don’t care, you just don’t.

I don’t care! you scream at the passing cars, making faces, So, huh, you want to come stop me? And they don’t. Nobody does anything. Not even your mother, who’s now just a toy figure in the distance.

Which proves your point exactly.

So Halley knows that if the street is a line of civic discipline, sticking to the straight and narrow, it’s also a place of liberating irreverence outside home.

And that when you’re particularly happy there is walking on air, which nobody tells you how to do because it’s believed to be impossible.

Well, let me tell you, it’s not.