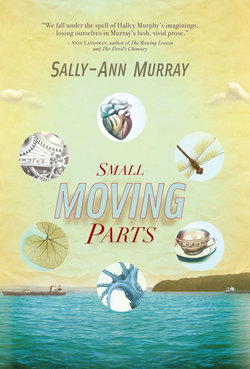

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Down below the Ridge

ОглавлениеThey don’t see many of their relatives, the Murphy girls, which may seem odd since their mother is from a family of thirteen. But they were all split up, so they don’t feel like family, and it’s only Aunty Agnes in Vanderbijl for the holidays sometimes, and Uncle Milton, who’s in Durban but all messed up because his wife ran off with his best friend, and then Granny, that time.

When it comes to the relatives on their father’s side, well, they do see some, mainly Nana, but their mother doesn’t like it. Doesn’t like them. Not his scheming brothers, always on the take, and not even nice Aunty Elda, who’s Nana’s much younger sister.

But Halley is fascinated by how sisters can be so different. Both women are smart and good-looking, so that’s a close match, although Elda has an exotic, sexy rumple. Louche, you could say, as Nora does when speaking of her, compared with the refined appearance and manners of Felicity. Olive-toned Brazil against rosy England. Worlds apart.

Elda isn’t even close to a granny, though of course nor is Felicity, because she’s Nana. Nana does the books in the back rooms for some business in Berea Road near the Tech College, but Elda is a saleslady at the Christian Dior counter in Stuttafords. Ah, non, vendeuse, she corrects, tweezered, pencilled eyebrows raised ironically. So Elda works in the store. For the fragrance house. Which ought to give you some idea of how glam she is. Stand-out stylish.

Elda and Byron (her good-for-nothing husband, quote) have a low house leafed into the bushy folds down back of the Berea ridge, the maze of lanes behind Entabeni Hospital. Always, though she doesn’t have the word, Halley pictures this space using hachures, the contour lines on a map showing the steepness of a hill. The closer together, the more intensely precipitous.

It is here that Halley and Jen’s father sometimes takes his daughters during his visits, since he has to take them somewhere for a couple of hours, and not too far, as there’s always somewhere else he has to be quite soon.

Gotta see a man about a dog, he said to Halley once, and she misunderstood, and got all excited, thinking about her dream puppy.

The girls love it off the Ridge, the kaleidoscope of house and garden and casual cousins, though Nora’s worried, and always asks dryly after Aunty Elda’s talons. Still so long, I presume? And what shade of scarlet this time? A tone of brutal amusement.

Nora knows about these people, make no mistake; she’s been trying to disentangle her life from theirs since the day, more fool her, that she agreed against her better judgement to go through with the marriage to Felicity’s middle son. Even now, unhitched, she’s battling with the ties that bind.

Halley is still too young, too in love with her father, to share her mother’s prejudice. But she is also unable to reconcile Nana’s elegance with the rougher, more working-class qualities of her sons. You never see a crumb on Nana’s tailored dresses, never mind a crease. Nana, everyone has to agree, has class.

About her husband, though, Halley didn’t know, since Grandpa Murphy was long dead.

What she’s picked up, little scavenged pieces, is that he had a wild temper and a liking for drink. Was a philanderer involved in whaling. Which seems far too little to make a person real.

Why does she remember some snippet about Grandfather Murphy sozzled and trying to row back to the whaling boat when it had left port without him? Never a clock-watcher at the best of times, he’d been particularly unmindful of the time that day, being otherwise engaged at an establishment in Point Road called Smugglers’ Inn. Which Halley thought would be an exciting Famous Five adventure at Pirate’s Cove, but really it was only a smelly men’s bar.

She knows places like that, because they’ve walked past on their way to the beachfront. A bar always had swing doors, split into two stiff, varnished wooden wings like a cockroach exoskeleton. Behind, you sensed a sharp clinking, softened by a darkened hum. If a man came out as you were passing, it was always the same white man, his face doughy, nose large and red. Then Nora pushed the children ahead on the pavement, hurrying along. But she couldn’t hide the smell, or the sign. It said Kroeg. Which was crook and spoeg, so you knew exactly what kind of man it was.

Her unknown grandfather Halley tries to imagine as a man in a hurry launching a rowing boat out of his sloshing headache into the open sea. She can’t think from where, since every point along the wavering sand and stumbling, rocky shore seems as improbable as the next. She’s sure he tried hard, her grandfather, made a sterling effort as men were supposed to, but tugging at the awkward oars she sees him so poegaai he’s unable to scull, so he’s soon swamped and topsy-turvy under he goes to his watery grave.

Halley, her mother says, sick to death of questions she cannot answer, Give it up! Forget about him. He was nothing. Certainly nothing to you, my girl. Though she thought how Mark’s father was a sponge and an old soak.

Your grandfather, so-called, he doesn’t matter and I couldn’t care less. What difference could he make to anything?

Halley doesn’t know. Forgets if it was difference she was thinking about.

Some days, Halley feels she can only breathe under the sea, which is dangerous and polluted, but it’s a challenge that’s been set for her. It could be that someone’s held her head under water or something’s bearing down drowning she’s drowning though who and why makes no difference to the flailing in her lungs and so she makes herself unique, a creature unknown to biology or myth, neither denizen of the deep nor fabulous mermaid, able to survive because no one knows her like, not seasoned fisherman or mad scientist.

Beneath the sea, not everything’s the trap of the bathroom, where to stop the blood from messing where it can’t be cleaned, she must lean herself over the bath and close her eyes while the red gushes from her nose, splattering onto the white. Like headaches and bruises, nose bleeds are nothing, lovey, so she mustn’t worry. But for a child it’s too much as if she’s dying, and even later, when it’s over and she’s lying on her back in the darkened room, the wet cloth over her eyes and the cold key under her nose to stop the flow, she gags on the plug of mucus that’s congealed in the back of her throat. When she manages to snork it down, pulling silently against her mother’s disgust, there’s a thick gobby clot to spit onto the hanky. A red, frilled relation of the intertidal sea slug.

Under the oily harbour waters, nothing escapes her, though she is neither hunting nor hiding, only finding a shape for the things in life she cannot alter. When she is so low, down deep, having descended through all the unmarked levels, she can look up through the dirtied water glass, seeing keels like gulls cut a wake through waves, or bob about, toy tubs in the bath.

She flickers away. Down in this water, against concrete pilings, enormous hulls segue into a giant, blank-faced underwater city, all the characteristic signatures submerged, and scrawled about with painterly crabs, and schools of quick, stripy fish that swerve as one from her projected touch. They can’t know. Yet they want nothing to do with her.

Beneath the lapping meniscus, a curved caul which on calm days is stretched to near-linear precision but buckles and lurches with bad weather, beneath, as if fallen from the liquid sky, is the bilgewater life of settled garbage. Almost illegible among the particled silt, shapes becoming other than they were, are rusted cans bellied into mussel banks, hauls of slimy eelish rope. Sheer plastic bags, wavering like trapped jellyfish.

Swimming deeper down across the bar out of the mouth into the body of endless water, she tires, and rests a while upon a length that can only be pipeline, although its tubular surface has been claimed as much as all the other debris by a film of whatever life can manage to take hold. As she lies chest down, arms and legs hanging sideways in the drift like kelp, unwilling to embrace the pipe, the barnacles prickle her torso. The life of the pipeline thrums through her until she seems to be generating the close-mouthed noise from an internal engine, and her lungs threaten to explode.

The first time she sees a body it is eerily white. So terribly white. It’s only a decaying shark, cast back or dead in the wasting water. This is what she tells herself, yet still she is brought up sharply by the fact of it. Lifeless. Life minus. Life less.

Everywhere is evidence of who she is, an ever-ghostly merging with the water that filters through her girl’s gills. And then there’s the truly submerged tenth, that part of the surface which haunts the buried margins, swept away and cast out, over the hills and far away.

When she’s up again on the surface, the house behind the Ridge is an imaginative extravaganza though it’s modest in size, not much more than a cottage which has grown to accommodate a growing family with self-built add-ons. Yet it seems to occupy the narrow quarter plot with all the faded, decadent sprawl and crumbling aplomb of a minor mansion.

The house has been made by Byron, is being made, under the influence of his off-the-wall inspirations, among which is tawny Aunty Elda. The feel is Spanish, although extremely loosely, as Nora likes to emphasise of the family as a whole.

Terracotta tiling and a square courtyard; fat pillars; flamboyant trelliswork that never crosses anybody’s mind as standing for burglar bars. And the walls! Uncle Byron splatters on a knobby plaster with a wonderful contraption. He pours the sloppy dagha inside and sets the dial, then points his workman’s weapon at the wall and cranks away. Instantly, a slight, slurried crunching as the two cylinders rotate against each other in opposite directions, and speckles of cement spray out under centrifugal force.

Eureka! Halley declared in amazement the first time she saw this happening. But was embarrassed when Uncle Byron winked at her. It’s called Spanish render, doll, he said, and then she thought he was correcting her because probably eureka’s not a Spanish word.

Since then she’s often toyed with the beautifully balanced idea of rendering a surface Spanish, and of rendering something Spanish by means of surfaces. And maybe – she can get herself quite excited – could be you could do other countries too, different nationalities. Though also she’s not sure about how she’d make the divisions, as down back of the Ridge, all is sinuous abstraction.

It’s the drink, Nora’s said. Thinking also of the constant loud music, of Elda’s draped, impromptu garments. The windows always without curtains, only gaudy, sequined saris wisped over poles.

Uncle Byron doesn’t do anything with regard for the regular, Halley knows; and her mother says he’s an out-and-out alcoholic who’s only ever succeeded in cutting corners.

But he’s an artist, Halley says defensively.

Indeed, replies Nora. He has an artistic bent. And Halley intimates that this is a statement about character.

For sure, Uncle Byron’s often more than mellow, ever a drink in hand. And when he’s had a few, he does get crude. Always telling one of his children to fetch him another pint, and when they’re too slow, he shouts jokingly they must hurry up, It’s like a drought in Zululand here, I’m pissing talcum powder.

Most vividly, Halley remembers the months of the perimeter wall. Each visit, however many weeks had passed, Mark and the children arrived to find Byron still shirtless, his shoulders oiled to teak, standing in his faded black boxers on the ladder, his monumentally slow progress strewn around him.

Her father went Howzit B and after Sokay boet he and Jen went inside, but Halley stayed to watch. Section by section, her uncle had been building the plywood formwork around reinforcing mesh, sipping from the beer bottle balanced on the painter’s step of the ladder. Now, he poured in a layer of slurry, packing it down but also leaving . . . why was he leaving those shoddy gaps? He saw her sharp face eyeing his work critically, and told her about expansion joints. So it won’t crack. She nodded, pretending indifference, as if she were actually worlds away, and this wasn’t the most interesting thing she’d seen in a long time.

On impulse, it seemed, he’d pull a bottle from his nearby sack and stick the empty in the mixture, neck towards the house, rounded base facing the road. Then he’d top this with more cement, hugging the glass in place. It was a long job. Slow. And it had to dry slowly, and be kept damp, curing into its best strength. And never mix more than you can use in an hour! That’s what he said.

When he’d done the basics on a section, he added shaped concrete flourishes, tapering cusps and towers which peaked and troughed at irregular intervals, the ridges stuck with shards of broken bottle glass – clear, green, a few brilliant blues she recognised from Vicks and milk of magnesia, and curved heels of hard brown.

If they stay late at the house, the girls, which isn’t usual, in the waning afternoon, before the sun sinks down completely into the Cato Manor bush, the rays rub the glass into a fireful flame of intense colour. For a few minutes, then, the reflective bottle bases pushed into the wall become shining animal eyes, but after, they turn back again, just into what they are.