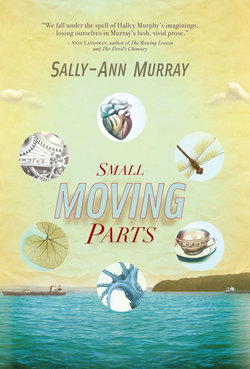

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Natural history

ОглавлениеAt the flats, Nature was almost the same as the ordinary outside, the fresh air where children were expected to play. So nature was what you were willing to make it.

Beneath the elm tree, out back in the dry soil, there were fierce little antlions that carved inverted cones in the sand; tiny, unstable pit wells to trap passing ants. If she got tired of waiting for nature to take its course, Halley dropped in an ant, then watched it struggle up the slope, its frenzy helping to shift the tide of grains towards the jaws of certain death. And all it took was a magnifying glass to work some kids up into a nervous anxiety: See the big pincers? Imagine that coming at you in the dark. You wouldn’t stand a chance.

And if anyone didn’t believe her, the intimations about what was possible, Halley magnified her tales with intimidating pictures from her nature-study picture books. She liked to point out the detailed scientific drawing of the enormous flea, monstrously enlarged. Close-up engravings of a tick and other creepy parasites. She’d even done some sketches of her own, inventing a whole hooked catalogue of cunning creatures with piercing, needle-sharp noses; with whiplash, tickle-tie electric antennae, and legs of brutal bolts and ginormous jaws waiting to bandersnatch. A ferocious collection.

Bugs like this, she’d say to her scabby little audience, They live on your body, yours especially, because you don’t bath so often. Sis. This one, see, soon as you fall asleep, it’s going to suck out your brain. If it can find any!

Halley was sometimes sorry when she managed to scare the other kids off, because it was much more satisfying to have them watching. Especially if she had some meths. She’d drip a little of the clear, purple liquid and carefully angle her lens, catching the sun tight and tilting tighter towards the burning point, waiting until exactly the white-hot moment when the antlion and the ant connected . . .

And then she’d zap them both.

Beyond the drip-line of the thorny elm, as the slope rolled sideways, the soil became more crumbly, and a downpour could wet the earth sodden. Puddles burped up and deepened to shallow ponds, belching out earthworms.

Not ordinary wrigglers, but nearly as long as Halley is tall. Examining a giant earthworm as it surfaces, she sees a fat blind tip, single pollex thumbing through drenched soil. It is a tunnel come alive, nudging the red-brown earth aside like a muscular liquid.

When you lie still, at night, waiting and waiting for sleep to come, you can hear the workings. The grunts and explosive squirting. Then it’s easy to believe that something’s in you, working overtime.

What’s got into you? her mother asks then, fed up with the child’s endless worries.

Outside, the tongueless, toothless worms swallow soil and vegetable matter, passing it backwards, over and out. But the castings seem much too neat to be droppings, and the little mounds she disturbs with her fingers look deliberately crafted.

Halley has paid attention in class; she understands that the earthworms help to pocket the soil with precious air, and she knows that the worms are nocturnal. But she never thinks that then she ought not to be seeing them. She completely misunderstands. Imagines that the giant worms, like Halley Murphy, have come out for the pleasure of the wet, to feel the moisture upon their thirsty skin, to shrug off the confines of familiar family and fusty indoors.

The worms cannot tell her how the rain floods their tunnels and cuts off their underground air supply; that unless they leave their homes, they will drown. That there is limited happiness for them in this saturation she loves, forced out into the light from the dark depths of which children, alone, are so fearful.

Though down there, too, the worms would report if they could, in the netherworld that brooks no refusal, are hidden engines working into the lightless earth, pipelines of gas, oil, sewage; barrelling cables with convoluted connection to the life that she’s learning to live on the surface.

It’s common knowledge that if you pick your nose, you get worms. A filthy habit. On that score, nobody seems to disagree. If grown-ups catch you picking, they get sarky. Had any luck there with the gold-digging, hm? Or, Care to share? Basically they make you appreciate how gross you’ve been, forcing other people to watch your revolting excavations.

So Halley is wise enough to pick secretly, though no one would take her for any kind of poekie-picker at all. And bingo, she gets worms. Which seems proof of the prevailing popular truth.

Out of the nose, into the mouth. Something like the predictable life-cycle of the bilharzia parasite.

When Halley gets worms, or worms get her, she has what’s called suffering the consequences, by which time it’s too late to promise, to swear, that on my oath I won’t do it again.

They are fine threadworms that veer and swerve like millesimal cobras on the wadded toilet paper, and she’s petrified, fearing that she’s charmed them out of the darkness. The worms are so insubstantial that in order to see them properly she must bring the paper right up to her eyes, which makes the worms enormous. She stares at them closely, their tortuous writhings. She feels hypnotised. And then suddenly she’s terrified that she’s doing exactly what the wily wrigglers want, which is to get close enough to her face to worm their way inside her nostrils!

When she gets worms, she also gets ashamed, so tells her mother only when she can’t bear her bottom itching any longer, since having worms makes known your secret dirtiness. Worms and dirt go hand in hand.

The other reason she holds back is because the medicine for worms is possibly worse than having worms in the first place. In a mug of Five Roses, her mother dissolves the granular, sandy contents of a tiny metal phial, stirring until the blend resembles a strong brew of ordinary black tea. And then Halley must drink it, even though she knows it’s an awful compotion.

Swallow! her mother instructs. Just drink it!

For Halley, it’s the smell. Like the unflushed public toilets where she and Jen are forbidden to sit on the wooden seat; they must first put a layer of toilet paper, the long strip eased and neatly folded into an almost oval, and even then perch, tinkling quickly. It’s hard, that, letting go while you’re also holding your breath and balancing.

So as she raises the cup, in the worm mixture she smells the lavatories across from the main post office in town. Not even the Ladies Dames, but the men’s urinals. You can smell them coming a mile off.

Halley tastes the sourness in the reservoir of her nose and sobs, her shoulders hunched at the thought of what she must do. She tries to do it. Sips a little in slow motion while Nora looks on, increasingly testy.

The messy texture of the granules, the suggestion of dank soilings . . . Halley thinks of the medication as a nauseating kind of sympathetic magic. Could it be that the worms originate in the phial, meaning that it’s the medicine she gets the worms from? Kooky logic, perhaps, but there it is.

Defiantly, she bangs the mug on the table.

Which is when Nora loses her rag and grabs her daughter’s head and finally forces her. As she tries to crush the girl’s squirming, grim-lipped refusal – Yorrkilllllingmemommmmy! – Nora is conscious of this as one of the rare moments when she could swear it’s Jennie she’s dealing with, not Halley. But right now there’s No Damn Difference and the child is provoking her to violence! Aahgod for a capsule that could just be shoved between locked teeth, stuck wherever, and it would be done!

Halley will not easily open her mouth, and even then closes her throat, so that the brew rinses grittily against her teeth, puddling in the pockets of her cheeks. She gags and retches. Her mother squeezes her face, pinching her mouth shut. And eventually Halley can do nothing except swallow, because if she has to hold the taste any longer then she’ll kotch, and have to do it all over.

Both Halley and Nora hate it when the girl gets worms. So does Jen, because although she’s never seen a worm near her body, which maybe is because she’s not looking, she’s obliged to endure the same sick treatment.

With the first bout of Halley’s affliction, Nora consulted Mr Cordial, The Chemist, who maintained you could not do one, it had to be both. So both of them it was. And that was over and done with, till the next time. Which there always was, because Halley played in the sand and didn’t wash her hands and, secretly, picked her nose.

But then, oh Holy Mary Mother of God, broeks asunder over the toilet, Halley discovered she had another kind of worm, much much more terrible than the others.

Big. An awful monster which stuck there, even though she’d bent herself double trying to see, and when she saw, straightened up smartly, gasping. It seemed impossible.

Halley pushed and strained, which only sent the worm into a clenched paroxysm, flickering against her cheeks. She was trapped. She felt it licking her. She screamed for help.

Halley could see that while her mother came at once to offer comfort, she really wanted to get the hell out of there, she was that revolted. But Nora overcame her squeamishness because she had no choice, really. The girl couldn’t deal with this by herself. She needed her mother.

Pulling, looping the long worm into a few sheets of loo paper, Nora wrapped it loosely into several thicknesses and concealed the unpleasant little parcel in her purse, taking it with her when she went to the orifice. Office.

After work, she walked home via the pharmacy, where Mr Cordial informed her that this, clearly, was no mere threadworm or pinworm. An adult roundworm, he said. In italics for emphasis, Ascaris lumbricoides.

And where there was one . . .

So both Halley and Jen should take double the quantities of the usual mix, and maybe, he advised, hands raised to entertain the possibility, could be Mrs Murphy ought to do herself too?

Nora takes her own measure in private, which is a good thing because my godfathers, she grimaces, it’s terrible. Why make such a foul medicine, she asks herself, and for children? You’d think the plan was to punish a child for falling sick.

To placate Halley, Nora said Well, at least it was only two measures. If it was one dose for the little worms, it could reasonably be ten for a worm big as hers.

Which freaked Halley out. Was her mother mad? What did her mother think? That she wanted to be a monster, some crazy female who squeezed worms like mutant babies from her bum?

But that’s what she did, after the treatment. All arsy-versy. A substantial bolus. They had to come out.

All the Kenneth Gardens children gravitate towards the park, which is what’s left of the gardens from once upon a time. Patches of worn grass tangled with clover and dubbeltjies, though even this green gives up near the seesaw and the swings, where it’s only red sand.

It’s shabby, all right, the park in Kenneth Gardens, but there’s no concrete, and nothing to mess up, so perfect for all the kids who run rough, rude and rowdy, who climb and corner and camp out; hordes of dirty savages who shriek through Kissing Catches and aggressive, thumping bouts of Red Rover Red Rover we call Marnus over!

Here, the children can happily play out the hierarchies they’ve learnt from their parents, though this place, this time, race isn’t the issue. It’s Europeans only, no question, but still there’re many lines along which to marshal cultural distinction.

The English-speaking kids curse all the time about Afrikaner vrot banana koeliesnot, and they know to avoid the dirty Dutchmen, damn rockspiders even if they’ve never seen the Transvaal. The Afrikaners steer clear of the rooinekke, because the Engels give themselves airs and graces, and seem to love everything about the Queen even if they’ve never set foot in England. Yirrah, don’t they know what country they living in?

With feelings like this, it’s necessary to have different schools for English and Afrikaans, which is a big help in the ongoing battle, though the same convenience does not apply to male and female.

Boys are expected to be loud and dirty; girls to be quiet, gentle and pretty.

Pole! graunches the woman in her nylon shortie nightie across the wash-lines. Pole! (And all those years, all that shouting, the boy growing from small to finished school, what Halley couldn’t believe most was why a mother would give her son such a stupid name.) But it’s long ten o’clock on Saturday morning already, and Paul’s got tired of waiting for his mother to sleep it off, so he’s ducked into the park. There’ll be trouble, later, because he’s forgot about watching the baby, but later’s not now, only thennn, which is when he’ll have to worry in case she tries to crack him.

Looking at the children’s mothers, many of whom are extraordinarily rough and ready, it’s clear that many lines have been crossed.

Tomboys such as Halley have also crossed the line. Busy with fires and dead things and making stuff, she hasn’t learnt the limits of what a girl’s allowed to do. And quiet, nervous Albie, another odd man out. His father is Uncle Zach upstairs, and he’s not pleased that his twin boys are so different. They look the same, those two, pale blue eyes, sandy hair and freckled as eggs you cannot tell apart. But Andre is always in trouble, which is right for a boy, while Albie keeps to himself. He’s clever, you’d think to look at him, sensitive, but proving very slow on the uptake. Even after many hidings, he won’t change from playing with dolls and teapots borrowed from the small ones who’re too little to say no.

All by himself, Albie sets up his blanket house in the shadows of the big trees, maybe imagining that no one can see. But his father . . . ? Uncle Zach is always watching.

At Kenneth Gardens, if your surname’s Murphy, the norm is that children from solid working-class families, families trying to make good, these children must not play, ought not to play, are strongly discouraged from playing, with kids whose parents are clearly lower class.

Which to Halley and Jen seems to be almost everyone.

From what they can gather, top of this category are people who at any time do bad swears (you must use your imagination, because Halley is not allowed to tell exactly what), and people who say kaffir, coon, munt, pekkie, or wog. Plus koelie, koelie mary, or sammy.

Be careful, also, of people who play loud music, and drink, either during the day or for most of the night. Men who hit the bottle, who can’t hold their drink like gentlemen, and hit their wives. Any men who chat up women on the off chance, hoping to score.

Chippies who smoke in public, appear in curlers outside, shout like fishwives, and swan around like floozies. Or strut. Any form of. Either braless, or wearing inappropriate clothing. Which includes any daywear which is black, gold, net or lace, and high-heeled, open-toed shoes. Particularly red. Oh, and leopard print is a dead give-away. These women may pretend to be housewives, but they are hussies and tarts. Strumpets.

Slags who can’t be bothered to hold their stomachs in. They’ve let themselves go; they are so far gone they don’t even care.

However, Halley knows to be careful. You can think the words which describe these women, but you must never use them. Her mother says the words are coarse, like the women.

And then in the category of offspring: in addition to the many children whose legs weep with the stigmata of Natal sores, terribly contagious and slow to heal, Halley and Jennie are not to play with children who are dirty, and probably have lice; those who say snot, and who have it (wet or crusty) under their noses. Children who say they live ‘that side there by the shops’, or who indiscriminately call adults they do not know Aunty and Uncle, without polite first names, or – heaven forbid! – Tannie and Oom.

And they mustn’t touch the grubby babies who are left to stew in sodden or soiled nappies, a disgusting rash chafing their inner thighs. Toddlers who are still in daytime nappies after age two, or who are using a dummy or a bottle, the same. Especially if this comforter hangs from a tatty length of string around the neck. Oh, and kiddies who are allowed to go to the tearoom in vests and knickers.

Further, Halley and Jennie must steer clear of families where there’ve been brushes with the law. For this, they must stay especially alert. One clue will be if they hear the words chookie or clink, then they must come home straight away. And obviously they’re to avoid the flats which already have a bad reputation; the ones where the sons are skollies or ducktails, and where there’s the bad kind of cigarettes. And they mustn’t assume that only boys are bad news. Some girls shoplift, or they’re just loose, tanning topless on the balcony. The standard line here is like mother like daughter.

And yet most of these fine distinctions are not merely of Nora’s making; they’re run of the mill, for in keeping with the times, many tenants work hard to set up and maintain the complex minor machineries of human differentiation which correspond to the big engines that keep the country running, regardless of what unhappy life gets crunched in the works.

Though for Halley, there is such a contrivance of prohibitions and restrictions, proprieties and transgressions, that it’s impossible to distinguish the well founded from the merely groundless, the morally persuasive from flimsy platitudes of precious personal taste.

Plus there’s the question of her father, which complicates things.

What she knows of her father, he’s handy. Mechanically inclined, people say, as if he’s tilted towards a machine and is going going gone.

Yes, her mother says, he’s down the tubes, and for Nora, that’s that.

Though Halley knows. She’s found out a thing or two by nosing; knows her mother keeps her father still, those bits she can. Like the unframed black-and-white photograph, a print so big that Nora’s had to press it flat in the back of the only book where it fits. Which is the Reader’s Digest Marvels and Mysteries of the Animal World.

So it’s a proper, serious photo, like the portraits of Halley and Jen in their smocked baby dresses and matching bonnets, taken by Norman Partington Studios.

A young man squats to inspect a titanic machine. The curved flank, though a hulking tonnage, is calmed beneath his hand. It’s all colossal cylindrical drums, bulging boilers, giant gibs, menacing cogs with enormous teeth and a piston whose stilled shaft is larger and longer than can be possible. But also there are small pieces. Finicky.

Leaning gently on the beast, the man is peering inside, his eyes asking What ails?

Their combined energy is throttled, yet both man and machine are distinguished by a tense, kinetic apprehension. The man’s nostrils flare, his jaw not exactly clenched, but still a degree too tight. Both expressions imply that he is impatient to get on with things, or has been instructed to do something he considers a waste of time.

This, Halley knows, is a ship’s engine. And this is her own miraculous father, way down in the engine room, bolted below decks within the bowels of the ship. A man among many, men mere flukes in the gut of a whale yet party to a digestive tinkering that serves an obscure intestinal purpose, the black clouded diesel belching across the oceans of the world.

Her father is a marine fitter and turner, whatever that means, and he must concentrate as he checks a component. Perhaps he’s shrouding toothed wheels, aiming to increase tooth strength where the amount of the increase will depend on the form of the tooth to which it is applied, and by clothing the pinion up to its pitch line, the threat of shearing failure – should the wheel be subject to unavoidable shocks – may be averted?

Something like that. On the passage bookshelf in Ixia Court is a thick study text called Machine Design, Construction, and Technical Drawing for Young Engineers. Neither new nor recent. 1919. Filled long years ago by Henry J. Spooner, C.E., M.I.MECH.E., M.INST.A.E., A.M.INST.C.E., F.G.S., F.R.M.S., HON.M.J.INST.E., ETC., with intriguing shapes and lines, shaded areas and sectional views, all to enable a young man to piece and disassemble, refit and subsequently make things whole. And such words to work through! The language is an enticing machinery of Couplings and clutches; Engine eccentrics; Stepped, helical and screw gearing; Piston packings; Bullivant’s patent rope clips and clamps.

The young men. They must be old now, she thinks, holding the book, or gone, tracing how insects have made tiny, angled tunnels through the pages, random letters disappeared. Some she can figure out from their neighbours; others remain total guesswork. A maze of sinuous boreholes. Musing, she sections the uneven tubes by opening the book here, and half through, and there, place-marking the pages with her fingers. Then welds a long, continuous length by closing the book into a single, thick chunk.

The eaten volume is a repository much too large for her to handle. Most of it is so specialised she can no more process the details than say, even with a knowledge of mirrors and secret compartments, how the magician cuts the woman’s body in two and subsequently joins the halves together again.

She knows she’s in the way, reading, blocking the passage like an immobile steel truss. Her mother and Jen must continually step over her (forty-five degree angles, lanky leg joists, chunky knuckle joints . . . ) as they pass from one room to another.

She does mean to move, she will – I will! – but somehow always lands up settling where she is, on the floor, because the diagrams haul her in. Her attention is riveted before she’s properly had a chance to think through moving, and soon she’s much too busy to go anywhere.

Every time she slides the tome from among its neighbours, imagining a slight grating as cylindrical friction wheels engage, she means to take the book to her room or maybe out onto the balcony, to get more comfortable . . .

But still she sits in the passage next to the bookshelf, her back contentedly against the wall, the morning sun streaming through the small bathroom window in such a way that it draws a rhombus of light cut by the lines of the wooden planks. She extends her legs up against the adjacent doorframe of the toilet, and reads. Looks, mainly. At. What is left to her. Spends hours in this complex, characterful, masculine company, never bored, absorbed in the personalities of nuts and bolts.

In the big photograph of her father, he’s not really doing his job. He’s not being an artisan but a model, sort of, though that sounds like a girl thing to do. He is demonstrating the accomplished skills of his ship repair firm, making the pretend seem real. He must look away from the photographer and the camera equipment as if he’s not aware of anything except the need to focus intently on his task, very serious-minded.

There may be people who remember this photograph from a brochure for . . . was it James Brown & Hamer? Dorman Long? Dorbyl? Elgin? Mark Murphy has at some point been employed by each of these engineering firms, gone from one to another, and been fouled for some misdemeanour. And sometimes, as luck would have it, has been taken back again during a shortage. Because when he works, Mark works; that nobody can deny.

But the photograph shows none of this. Instead, it extols the collaborative virtues of industrious man and humanised hardware, the picture an implicit slogan: Your valuable marine machines. Safe in our expert hands.

The idea is emphasised by her father’s youth and handsome, swarthy muscularity, though he is more clean-cut than she has ever seen him. Clean as a whistle while you work, which is much too clean to be true. Even the engine oil staining his boiler suit resembles sculptural shadow rather than regular monkey grease.

The clean dirt is clearly an effect of some kind, Halley understands, enhanced by the invisible equipment used to light the scene. This is out of the picture she holds, though if she imagines the fullest possible image, she knows there will be a camera and another person in the missing space.

It is a lovely picture, at once solid and lit with the aerial substantiality of sunlight breaking through cloud. In his mechanic’s benediction, the rays gleam off her father’s cropped black curls, brilliantined with Brylcreem.

The photo is perfectly radiant, which must be why her mother keeps it closed up in the big book, for fear of being blinded. She’s surprised her mother hasn’t thought to offer it to the OMO people, for an advert, as they’re right here in Durban. They’re called Lever Brothers. The same people who make Sunlight, down in Maydon Wharf.

Halley imagines the ad. She would . . . okay, so there would be the beautiful photo with a box of OMO washing powder angled across the corner, this being the only blast of full, powerful colour. Though maybe they should also have the word OMO along the bottom, and dots . . . leading up to Out Machine Oil. Pretty clever, huh?

OMO! Women would know that the single word meant the spots and stains would be magically gone, and no one would have to wrestle for hours with the dirt.

Every weekend at Ixia Court, first thing on Saturday morning when Nora returns from market, the girls must tramp the washing in the bath with grated Sunlight while Nora bends and rubs with the green bar of soap uppppp and downnnn the ridged washboard for the tough stains. Then they do one rinse in clean cold water and after that it’s let’s go do the twist with the sheets, Halley holding one end of the wet, twisted rope and Jen the other until most of the water’s been squeezed out.

If there’s really a lot of heavy washing, Nora pays Mrs Volans next door one rand and they borrow her freestanding mangle, which gets the wringing job done more quickly but you have to be careful about crunching the buttons, and anyway Halley gets queasy when the washing comes out stiff and flattened, the people completely wrung out of the clothes.

At Kenneth Gardens, some of the women pretend Nora doesn’t exist. Others make their bodies very flash when she’s nearby, hoping to provoke. Some look at Nora skeef, only their faces goading.

Bladdy Nora Murphy, who walks around with a ruler up her backside and her nose in the air. Mrs High and Mighty. Lady Muck. The hoity-toity walking dictionary! Who the hell is she to talk? A backvelder from Bloemfontein who dirties her gundies just like everyone else. There’s her washing there by everyone else.

A number of the men have made overtures to this remote, attractive divorcée, but she’s spurned them, every one, so she’s obviously a frigid bitch.

Though that hasn’t stopped them from trying. They agree that Nora Murphy must be getting it somewhere, hey, a woman who looks like that. Lucky bastard playing hide the sausage. Two small kids must be a bit of a handful though, don’t you think? When would she get the time? But she must, surely; no way such a hottie could do without.

Nora’s good friends with Aunty Beulah upstairs, and the woman next door. They admire her, what with Mark, who’s done his damndest to drag her down. Maybe she’s hardly got two brass farthings to rub together, like everyone, but Nora’s got good manners, self-reliance, determination. And she’s so good with children, her own and all the others who hang around at 4 Ixia on weekends because there’s sure to be plenty on the go. To top it all, she’s chic. And my, doesn’t she dress her little ones beautifully?

So in this place where people live hard to make up for hardly living, Nora does everything she can to look after her children like a good mother. She loves them. People say she adores them.

But look, if she wants them to be good, she also wishes for them to be happy. Which means between this and that and here and there, all the do’s and don’ts, they make some friends. Which is what they need, being children. And it comes in handy for their working mother too, because she can’t always be watching over them.

Going places. All of them together, their mother and lots of kids. Sheila, Deon, Marnus, Wendy . . . all the way down Francois and far along through to Bayhead, where they spent the day at the mangroves. At low water, the tidal flats emerged in wind-pecked pockets and patches, sand suddenly more extensive than water. A mass of forested shoots fingering up from a glutinous, tarry silt.

The children’s bare, panicked legs were sucked in and stockinged black. Crab colonies, each crab with a carapace daubed a different shade of blue – turquoise, indigo, jacaranda purple – and many wielding one enormous red pincer, either horrible handicap or helpful come-hither. As the children approached, the crabs were pulled in unison into the thousands of puckered holes. And then, after some immobilised minutes in the dappled mangrove shade, they peeked up one two tens hundreds, and the skittish messaging began again.

So many birds. Spoonbills delicately dibbling and dabbling. A peck of mohawked pelicans chuntering down towards the water.

Halley watched her mother’s patient happiness, and thought of her as a grey heron, poised, but with a yarn of hidden gut tangling its toes. She seemed a woman held by a wary caution come too late, yet still spiked with the longing to gulp things whole.

Once, they even spotted an actual flamingo. Just the one, so extraordinarily solitary, although Nora spent long minutes staring into the sky and scanning the scrubby shore.

Ask your father about them, she said sadly to Halley, All the flamingos in the bay when he was small. This is nothing compared to what they were. You didn’t need to know a hawk from a handsaw to realise that.

Which made the other children glance up momentarily from their digging and splashing. At Aunty Nora, and her riddles.

And then she recovered her motherly centre, and pointed very slowly to a tiny wader tipping along the shore. Shhhh. See that one? A little stint. Come all the way from overseas.

Halley could hear that the children were meant to be amazed. By migration and endurance. The incredible distances and accumulated knowledge. But they said nothing, only Marnus, who said Oh.

She herself thought little stint big stunt rig splint wrong shunt, wandering off through the bottomless sound of her mother’s words, hieroglyphic as bird prints upon the sand.

Far worse than Kenneth Gardens, even lower down the scale, was Flamingo Court, the cheap flats on Umbilo Road near the beginning of Bayhead, where the flocks of flamingos were long gone.

The Murphys always hurried past Flamingo Court when they walked that way with their mother, though they had once been inside, past the dank inner well and rubbish-strewn stairs, up into the sour stink of the clunking lift. Because their gran had lived in Flamingo Court for a time. Granny Margery.

With Milton, her youngest son, Granny Margery had been staying in a low, quaint block off the Embankment. Small, but a nice place; a breezy balcony curved over the busy street. But then Uncle Milton got married and moved out and the rent was too much for just one.

So Nora got involved. She didn’t know her mother, or not well; but she couldn’t have her on the streets. Understood that anyone had to live with some decency if she were to think of herself as a person.

And the only solution was a bachelor flat in Flamingo Court. Sight unseen, Nora arranged the move with the council and paid for the truck. And once her mother was in, she and the girls walked down from Kenneth Gardens. But just that once. Because they were so stunned that after they’d spent enough time to be polite they turned around and never went back.

Claustrophobic at the smallness of the flat, the stale smell. Shocked at the state of the lift; the incarcerating steepness of the brick tower built around a stagnant central well that was cut across by bowed, dripping wash-lines.

And horrified by the story. Granny could not keep from crying as she told them of the small child who’d been snatched from the stairs where she played while nanny, stripped to her bra and petticoat, washed herself top-and-tail with lye soap at the servants’ coldwater concrete wash trough.

The barbarism, Granny cried, How could you explain it?

But their mother only said in a choking voice that explanations weren’t necessary when savagery was everywhere.

Turned out the girl had been taken by a neighbour, and after a few days, at a time when he was done and sleeping, his girlfriend had unlocked the door and told the little one to run, fast, find someone at the wash-lines.

And they call themselves white people, Marge cried in disgust as her daughter tried to soothe, though not knowing where and how to touch the other woman’s raw distress.

For her mother, Nora saw, this wasn’t a story but a measure of her own helpless despair. Living was so hard! Could it not be lived in some life better than this?

Even before, Granny’s life had been hard, Halley knew, though she didn’t know all the details. Only that her mother’s father, who would have been her grandfather if she’d ever known him, had been a mean, tight-fisted Irishman. Which wasn’t how she’d imagined the Irish at all. Not with all the saints and four-leafed clovers and leprechauns, all that beautiful green.

Story had it that Joseph Alexander Hoare was a dour, miserly government storeman. Each skinflint morning before work, he instructed his wife to furnish him his fill from the food in the kitchen, then he keyed the cupboards against the growing horde of canny, hollow-eyed thieves. They weren’t all his, and that was explanation enough.

Nothing was apportioned children, not even words. Not: No food until dinner. Or: There is not enough.

Just a wordless, methodical slicing, issued to himself, followed by spread, eat, lock, pack and leave, jangling his way to work past the tight clutch of children’s faces.

Every day.

Every day he left his wife with the surd of hunger somehow to appease, though her options were so limited.

And never any privacy for what she had to do either; always the waiting, watching children, their thin-chinned faces shaped like hers and, like hers, begging for some small remit.

So Granny Margery’d had more than a tough time of it, and nothing was about to change with Flamingo Court. She’d just got there, those flats, but she had to get away. A person could not live like that, she cried. Everything about Flamingo Court was wrong. It was depressing.

And much of it was true, for Margery, who was trapped there for a long time, however much she loathed the place.

It was too isolated! Granny hurled the angry accusation at Nora. The dark passages were unsafe. The whole block was a haven for the poor-white criminal element. She’d been accosted in the lift by skollies with knives. The lift was always out of order, her legs couldn’t manage all those steps. Even, it was too far from town.

And didn’t Nora appreciate, she accused indignantly, that a month’s return bus fare into the city cost more than she was saving by living there?

For Nora, her mother’s relentless jeremiad cast her own scorched daughterly love out of the frying pan, and she had to suppress the truth of Flamingo Court in order to think better of herself and her well-intentioned efforts.

And as for Halley and Jen. Their relief at walking away from inside that terrible block was vertiginous: momentarily, they saw themselves as occupying the heights of glowing good fortune, and the brute fact of Flamingo Court became spliced into their sistered silence, part of the splitpole belief that the worst, at least, had not happened to them.