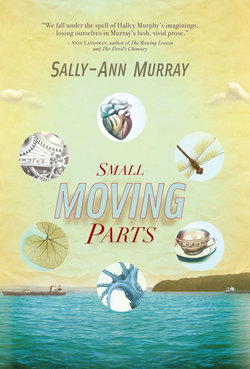

Читать книгу Small Moving Parts - Sally-Ann Murray - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Entrance

ОглавлениеUnder Nora’s skin a shape moves – heel, hand. She knows what is being formed, but even after all these months cannot accurately judge. The baby is yet a jut into the unknown.

Nora rests a palm upon her taut egg, incubating. It takes so long. For months you hardly show and then bam, you’re nothing but a belly. Sometimes, teetering towards the future, Nora wishes it would take longer, but knows she has no say and that she cannot procrastinate. It will come when it comes.

Beneath her hand she flinches as a limb shifts, stretching her already tight skin. The discomfort! She is being elbowed aside from within until surely this must burst. She must. She’s bursting to wee. Again.

And as she sits, releasing, she follows the outline of the hidden child, the skin losing the last of its elasticity, thinning to a substance like hard, sheer plastic.

A sharp knife held firmly against the dome, the slightest of pressure could cut it, this stretched material, without either much blood, or pain. Just slice and peel. This is what she thinks.

The foetus pivots again with a heavy, rolling pressure, so acute against her intestines that Nora winces. When she worries about how big she’s getting, the clinic sister shrugs. You girls . . . What did you think? It goes in, it comes out. And it’s got to come out the same way it went in.

Which wasn’t really an answer. Though it’s true Nora’s own questions had been implicit.

Young as it is, a foetus knows that life means more than itself. That making ready to be born entails links and ligatures and dependencies. That life depends, because the thread is thin.

It may be that the cord is tough as old boot leather, and would take some gnawing if a knife or scissors were not to hand. That it can strangle a baby, this slippery loop of flesh. Which only means, again, how fragile a thread it is. Think how often such a cord is severed, though the cutting release a child into god knows what.

For now, the mother eats, drinks, worries, reads, and all is food for thickening and thought, pumped and channelled and sifted, growing the new beginning that is starting to become a being to be born.

Inside her mother, the mind’s eye followed traces of worlds. Call them eidolons or phantoms, sensory flashes, maybe just the growing fruits of a wild imagination as the embryo grew into charmed and chary life . . .

The busy cells burgeoned forth to some lost port of call. Schooners, ruggedly rigged, fore and aft, and clinker-built clippers, clenched with copper nails, the air aclank with the rattling of rigging. Everywhere were loud male voices, carried on the wind with wooden crates and roped bales swinging from winches, a vessel about ready to sail. And, inside, a huddle of dark shapes that might be animals, or . . . people? The stench ballooned, but within earshot was only the lap and thump of fluid life, the harbour of a mother’s heart.

Sometimes, hosed out by coiled water, the stink of rotting flesh dispersed, the melancholy clamour abated. Then in the stillness the foetus felt itself a waxing moon, gathering amid the austere, intangible silence of stars. And suddenly an eruption and a rictus a black hole a meteor shower that seemed to ricochet from a sundered earth with all the force of a volcanic belch. The cramped body cringed, finger buds flexing, but no, it was nothing intended to cause distress. Merely the inner workings, an undigestible rocket uncoupling its supernumerary parts, debris jettisoned and harmlessly atomised in the hold of the astral atrium.

Occasionally, in the confined, overgrown intestinal tracts, there broke an erratic, veinous path which gave onto riddling vegetation, the forested tracks of men and animals. From the heights and depths of its short-lived experience, the baby saw elephants rolling like slow, unstoppable boulders, behind them hunters tusked with guns. Through the bush they tasked, big feet and small, over ridges and rimous rifts, down to a red-strewn lagoon in which another body already lay, the waters washing over the felled mounds of meaty rock. Slowly, logs loomed onto shore, dragging chunks of feast into the motherless murk.

This, the baby saw within, is what people did. Men took their spears of fire and went out hunting, carving graveyards of memory. Some disappeared, though there were always more that remained. A few, impressionable, made pens, flighted from dead wings, unfolded pieces of leafy parchment and nibbed the hunting into feathered homesteads. For this, women were gouged upon the ground into red furrows, and rows began to sprout, faces turned towards the sun, their endless needles piercing in, and under, and through, stitching it all together.

Spirals of time turned upon the balcony of this hiding place, the baby lying inside her mother as the woman lingered, sometimes facing seaward, determined to be pleased to have found her place.

Though under the sea lay lagan; a wreckage of goods and timbers awaiting retrieval, no easy foothold on the human world.

Nora’s first child is born at Mothers’ Hospital, with its curled foetal apostrophe. Mothers’ is run by the Salvation Army, and the winged badge which heads the birth register bears the motto Blood and Fire. Which seems about right.

The labour is as considerate as the current medical conventions allow. No superfluous extras in the theatre, which includes the father, and in the interests of hygiene would include the mother too, were this possible. Parents can look forward to a whole lifetime ahead of them with their child, so why they must be so watchfully present from the beginning it is difficult to understand.

The nearly new mother, never so naked again until the next time, is exhausted, her body at the mercy of senses which amp between numb obliteration and a fierce, sharp branding. She is held at the end of the waiting iron, and it does not withdraw until the burn between her lips reads ‘mother’. It is redder than a violent wound, heavier than a slaughtered ox, and bonds her to this child.

Aaaggggh! she mutes a blur of pain, Does it have to be so sore?

The doctor, though, tells her it cannot possibly hurt that much. It’s merely labour, Mrs Murphy, not much different from freight-forwarding. Around the world, across the face of the earth, there are women having babies every second, so she must stop making a fuss. Your baby will come, he says smiling, All in Mother Nature’s own good time.

Which will also teach her about being more careful, he is maybe thinking. And about her relative privilege. About what it means to be a woman.

When the baby eventually presents, the twisted purple cord a limb attached to her bloated belly, the deliverer slaps the slippery little body upside down into the world. Which would have been a useful lesson, if only she’d remembered.

The mother, though neither cut nor torn, lies like a carcass. The business done, the room buzzes, busy with this and that. It might be blowflies that surround her, though they are nurses. Steaming, swabbing, sips of water raised to a parched mouth, until she is wheeled away on a gurney to recover in her crust of leakage. She feels peculiarly limp. Hot and cold. And before Nora knows what’s what and what’s hers and where’s the nursery, the baby is swaddled in rows among other cribbed transparencies while she lies childless and alone in the general ward.

Having done its time, this particular baby is full term, and punctual, so in these respects it delivers, establishing the lifelong patterns from the outset. As it crowns, it is clear that the child will be born with a caul. The thin foetal sac continues its hold at birth, sticks to her scalp, giving her the animal newness of a drowned kitten.

The nurses whisper, exchange remarks about the psychic gifts and omens that a caul endues. Does the mother want to keep it, good luck against a sailor’s drowning?

Her No! is so firm, so forceful and abrupt, that they wonder for a second if she’d thought they were referring to the baby, but that’s a scrap of flesh she has to keep because it’s hers, and she no mere slip of an unmarried girl who might consider giving it away. Though by the looks of it, they agree among themselves, the baby might do it for her; it’s half gone, might not even be up to saving itself. The infant weighs in at a puny five pounds.

When the caul is lifted and thrown into the bin of medical waste, another striking mark is revealed. The infant has a marked double crown. Two crowns which oblige her scanty hair to perform extraordinary accomplishments, whirling in opposite directions upon her bony tortoise head, as if she is simultaneously being whipped this way and that by an imperceptible wind.

The newborn is noticeably underweight and restless, with surely the most wrinkled, angular, unprepossessing body ever seen. Has she, perhaps, been stretched on a rack, then abruptly released? Why is her body so insubstantial, a ghostly form lengthened into two dimensions?

And she has oddly light-coloured eyes, this child, faint green, with dark circles baggaging beneath. She looks too worn to be freshly arrived in the world, so that visitors who see her shake their heads and cluck.

She watches them, already a watcher who will not sleep, eyes zithering. She is sleepless and scrawny, which annoys the nurses, since all she’s had to do so far is spend nine months laying up stores of fat, relaxing on a comfy velvet sofa, so to speak.

What’s the story with this one?

Nora Murphy doesn’t know, and she is anyway heartily sick of stories, so she sleeps until such time as she is made to surface, hauled from the depths of exhaustion, given a child, that child, and told to feed. Thrown in again at the deep end.

But she quickly rises to, forced afloat by her newly inflated breasts. She is a buoyant body on a sea of white sheets. Nora doesn’t like it, being mammothly mastoid, but she must start to learn the little she will come to know about being a woman with noticeably big bosoms. And she’s a wreck, discovering their real purpose; didn’t even like the other fumbling that much, all Mark Murphy’s manhandling.

Again, there are hands all over her body, women’s this time, and voices instructing her No, no! Not like that. Here. And her engorged flesh is gripped and painfully flattened, directed towards the ugly gummy mouth which must be teased with the tit until it clamps over the nipple.

Which is a serious shock. For never, ever, has Nora thought of herself as a woman with anything as coarse as tits. The word itself has never touched her lips because it does not apply to her, and nor will she use such crudity to diminish other women.

Though it has surely tricked her all these years by hiding. In ordinary stitches and authoritative institutions, in irregular appetites and regular dentition.

Hell! Tits are everywhere for the looking, Nora thinks, mocking her own exhausted naïveté. All shapes and sizes. I was such a t- . . . an . . . idiot for not realising.

Come now, Mrs Murphy, the ward sister declares, Baby is hungry. Baby must latch and suck, so that she can eat and grow. Just keep trying.

Oh lord! Nora harries herself, Isn’t that always the damn case? Trying, trying! Why won’t some things come more easily? Doesn’t she deserve a little luck?

Otherwise, Sister says, stating the obvious, taking in the child’s puny body, This little girl will be in trouble. And then more sternly: Do you want your baby to be in trouble?

Why would I want trouble? Nora’s head silently countermands. As it is, you hardly have to look and trouble finds you.

Eventually, however, there’s a trickle, and the sister says Thaaat’s it, clever mommy, yes, and Nora feels a warm, prideful rush, induced against her will by the official praise. She feels herself glowing with simple achievement, though aware that it ought to be galling to be treated like a simpleton, or a child.

Still, however, it is the child which doesn’t seem to know what to do, when Nora had thought this whole breastfeeding business was plain instinct. Why is the baby such a slow learner? What’s wrong with her that she doesn’t suck? Christ, she’s fallen off again, the stupid tongue fat as a slow-witted slug.

Both Nora and her baby are ignoramuses, and the sisters of the secret knowledge systematically intervene and re-apply the leech each time it drops off the nipple into a fidgety pausing which isn’t sleep, wet tongue tipping in . . . out . . .

After much trying, she’s on fast and there comes a curious, vibrating release as the milk begins to pulse in sharp almost electrical spurts that induce a reciprocal yank deep between Nora’s legs, as if the fluid is coming from her uterus. The tugging is insistent and then gradually abates, until eventually, which does not take that long, Nora finds with surprise that the vat is dry.

She is empty. It is done.

Uh, not, actually, since a mother must always have extra reserves. So the procedure is repeated on the other side, the reluctant feeder chucked and tickled towards further attachment. Gradually, Nora’s other teat gives the infant a slow bloating, after which the baby gapes and wails, abdomen held in a tightened distension. There is probably something the mother must do, but Nora doesn’t know what, as she’s burped the infant already.

This feeding, feeding this thing, she is expected to do every three hours. Not quite demand feeding, since it is she, the mother, who must demand of this fussy child to feed, must make her want it until the child gains the desired weight.

Nora does not think she can bear to go through this whole palaver eight times around the clock. But it’s tough. She has to.

For now, it’s: And how is Mother doing? And is Baby full?

And in response to Nora’s question: No, you can’t. First, you must get up and come to the nursery to change Baby, because after the feed there will be a stool. Then go back to the ward, as Doctor will do his rounds later, in maybe half an hour. Then all of you new mothers – a hand indicating – must come for Baby’s first bath, to learn how. After that, you can have a little wash if you want, but if you’ve got stitches down there, careful, do not get them wet. And then the duty nurse will bring Baby again for its next feed.

And lastly, as a studied afterthought: Is your husband coming to see you properly at visiting time, Mrs Murphy? Doesn’t he want to hold the baby?

After this, Nora can hardly remember her question, but it’s in there somewhere, squashed very small. And as she watches the woman in the white uniform, insensible white lace-ups bustling beneath, a watch pinned upside down upon her chest, Nora thinks: Who is this baby you are talking about? Why do you make it sound as if there is only one baby for all of us? Do you want us to fight for it? Me, I’m not up to squabbling; if there is someone who wants the baby more than I do, she can take it.

Though there is nothing to say but Yes, as she looks at the other mothers who lie among their florists’ shops and flowered gardens, the air abloom with delicate scented notelets.

She sniffs. Wonders if they’re trying not to look as if they are watching her. She can’t tell, finds it hard to see them properly behind their bouffant bouquets, though she is choked by the beautiful aroma of love which drifts, wafts, circulates in this clinical air.

He has his faults, make no mistake, but the new father has already dropped in, though wearing overalls and empty-handed – the quickest of Hi’s and Cheerio’s. He’d stood outside the nursery, his nose almost against the glass, the new oddity indecipherable, although he tried to follow the clues. Frowning.

Until he came to know what he was looking for, it was only the label that was supposed to provide the proof, though he couldn’t be expected to read from such a distance, identifying his personal belongings like a standard uniform boxed among the rest.

’Scuse lady, he stopped the duty nurse, I’m here for my son? Murphy’s the name. Where’s the little toughie?

But something had happened to the boy, and there was a girl, instead, which left Mark flustered. Speechless, to tell the truth. And not even chubby or winsome, his daughter, but skinnnnny. A horrible thing, was all he felt, hardly endearing.

Which is not a promising start. Sure, so she’s not born in China, and no one sticks needles into her body because she’s a girl, twenty-nine thin teeth floating in her fluids and piercing her organs, discovered years later when she’s X-rayed for aspecific pains. And her mother is not a young woman in India, risking an illegal foetal screening, her femicide unwittingly feeding the demand for child brides.

Nothing this big, the Murphy baby. She is just a girl, and all that followed was a father’s disappointment. After that let-down he’d put his head into Nora’s ward to say cheers, but the wife was sleeping, so he didn’t have to say anything. He definitely didn’t stay. Couldn’t. He was working a major repair in the floating dock.

For some reason, however, in the short visit he’d become fleetingly aware that his wife and daughter were coupled. Female. And that he was the only one in the new family with no tag on his arm, that paper bracelet thing.

Hm. He shook his head, not vigorously, just the shudder of a dog, dreaming of shaking dry. Quashing his thoughts, Mark Murphy headed back to work. The foreman had cut him a little slack that day, kid being born, but he couldn’t afford to screw this up.

After more than a week Nora leaves hospital, and now the baby is stronger; she’s a stayer after all. But so small. Needs custom cloth nappies cut from flannelette, and she’s still far too tiny for the cot. She’d slip through the bars like a jumper from a high-rise window and break onto the floor.

She would. She could die. Could be left for dead. Which is something to think about, and the weary mother does. Sometimes.

But instead she puts the newborn in a shoebox, her mattress a small hot-water bottle wrapped in a receiving blanket. It’s done with something resembling care, carefully, because Nora is not one to be careless, but still the baby looks like an abandoned kitty, rejected by its mother and being raised by hand-held titty bottle.

None of which interests the child when she is told the anecdote, so many years later. Instead, she thinks of the fascinating system at Cuthberts shoe shop for giving and receiving change. How the saleslady puts the customer’s money in a brass cylinder which is inserted into a tube and shot, via air, along a system of aerial tunnels to the next storey of the building. It’s called pneumatic, this magic. Then a clerk in the Accounts Department works out the change, writes up the receipt and puts both in the cylinder, which is dramatically returned to its place of origin. The Accounts must always be up, Halley thinks, and down there, where the customer waits, the receipt, the change, appear in a whoosh of arrival. As close to a gift from God as you’re likely to get.

Halley imagines the customer’s shock at finding a tiny baby curled in the cylinder. She imagines it really happening, without courier or covenant. What a surprise! She thinks that getting a baby might actually not be that different, even if you’re the mother.

Did you feel that the baby being inside was like that? Halley asks her mother, And did you like to think about what I would be like? And Mommy . . . Mom, when you saw me, she persists, Did I look like you? And did you like me?

Nora glances at this strange child stranded there with her. She says What do you mean, Halley? Can’t you say clearly what you mean?

And when the girl looks offended her mother says to Slow down. That she must talk more slowly if she wants people to understand what she’s trying to say.