Читать книгу Conozcamos lo nuestro - The Gauchos's Heritage - Enrique Rapela - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

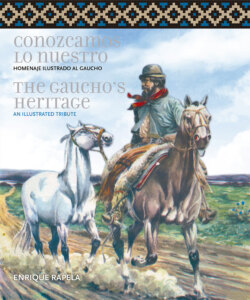

ОглавлениеPortrait

of a Pioneer

In the circulating biographies of Enrique José Rapela (1911- 1978), some precise strokes stand out. Even though he completed high school, he was a self-taught person regarding drawing and watercolor. Descendant from an immigrant family but seventh generation of Argentine people, he was a direct expert on gauchos’ topics because he administered La Carolina, his mother’s estancia, in Roque Pérez, close to Mercedes, in the province of Buenos Aires, where he was born. He was a passionate entrepreneur, scriptwriter, draftsman, editor, writer and historian, living in a golden age where great paradigms reunite: the historical revisionism of the 1960’s and 1970’s; the boom of graphic media —both magazines and newspapers were read by thousands of people all the time and the whole week—; and, finally, the profuse spreading of the national folklore with performers like Los Chalchaleros, Los Cantores de Quilla Huasi, Horacio Guarany, Eduardo Falú, and the boom of festivals and peñas [meetings where folk songs are played].

The native was consumed and spread in the city, but the morning graphic media were the place where the Creole cartoon was established as a genuine genre. In Cirilo el Audaz, published in the newspaper La Razón in 1939, Rapela narrates the adventures of Cirilo Cuevas, a gaucho who runs away from the law and seeks protection in the lines of Rosas’ army. The outline of that cartoon is repeated later with other characters and it becomes an archetype that perceives authority as aggressive and corrupt, and for that reason prefers to stay outside the law. There are historical-political references, like the Campaign of the Desert, the War of Paraguay; and personalities of our history, like Nicolás Avellaneda, Adolfo Alsina or Juan Manuel de Rosas are mentioned. The text was not in the typical speech balloons of the cartoons; it was located under the drawings. Regarding the speech, there is a nationalistic view that defends the countryside, through the archetype of a hero who can do everything with very few elements. In this way, in the whole cartoon, the gaucho, to a large extent alone with his strength, his ingenuity and some kind of luck in his favor, became a winner.

This didactic involvement with the diffusion of this environment could be placed after 1872, when, as the Argentine historian Bonifacio del Carril held, the gauchos were a true social class. Rapela himself said in a conference: “In this way we will understand that this wonderful country was not inhabited by useless barbarians, lazy people with bad habits, as a huge systematic and perfectly organized campaign, supported by people who only conceived as civilized what comes from overseas, rejecting the Latin Hispanic origin, repeated”. He was clearly opposed to a matrix that fostered the appearance of a new kind of citizenship that justified “domesticating the wild”. For that reason, the time chosen is the same of the conflict between Domingo Sarmiento and Juan Manuel de Rosas, an epic that turn into the book Civilización y barbarie. Vida de Juan Facundo Quiroga y aspectos físicos, costumbres y hábitos de la República Argentina (1845), where the gaucho was pointed out as the main responsible for the cultural backwardness that stopped the development of the country. It is an essential node of our history, but also the result of the imaginary of the time, where extending the limits was imperative to get access to the organization of the Nation State.

Due to this revisionist trend, the archetype of the gaucho outstands thanks to the features of an already obsolete orality in the countryside, such as “apestao” or black “virgüela”. Also the garments were recreated after having access to documents from historical museums, to the point that even the drawn weapons were trustworthy descriptions used in that time. That vocation for the graphic representation of the material culture —both in Rapela and in some of his peers— was increased by the degree of closeness to the countryside environment of the plains, but it was based on historical research and literature by authors who described the period, which configures a didactic value that provided certified information to generations.

THE GAUCHO IN PAPER

Carlos Gilberto Landa and Julio César Spota, from anthropology and historical archeology, went deep, in an article, about the relevance of Argentine cartoon, because some thematic relations, true critical revisions regarding the process that conformed the national past were developed there, emphasizing that “cartoon rose, through aesthetic means of massive diffusion, as an alternative approximation to that past”. The authors understand that the modern concept of frontier was anticipated in the gauchos’ cartoons by “elements of reflection related to processes of intercultural contact, dialog and conflict that were incorporated only in the 1980’s as a paradigm of common reference within the circles of anthropological-historical discussion”. The setting of works like Cabo Savino, by Carlos Casalla; Lanza Seca, by Guillermo Roux; El Huinca, by Enrique Rapela; Martín Toro, by Jorge Morhain and Bernoy in the drawings; Lindor Covas, el Cimarrón, created by Walter Ciocca; Capitán Camacho, with a script by Julio Álvarez Cao and drawings by Carlos Casalla –just to mention some titles of the extensive artistic production— showed, in their entire complexity, the different social links, the ways of cultural exchanges, and the case of the mutual economic dependencies existing among the white, the indigenous and the mestizo groups.

It was in the 1940’s when what can be called “golden age” of national cartoon starts, and its milestone is the appearance and consolidation of the cartoon considered serious and adult, with the magazine Intervalo of Editorial Columba in 1945. The magazine Billiken was already being published for children, and Patoruzito, the child version of the character Patoruzú, for young adults. In 1945 Patoruzito published Lanza Seca by Roux, who writes a series on the Conquest of the Desert and the war against indigenous people. We must remember that Patoruzú was published for the first time in the last page of the newspaper Crítica in October 1928, when its creator, Dante Quinterno, was 18 years old. The main character was the last offspring of the Tehuelche tribe, son of a rich cacique from Patagonia, a paradigm that also describes a cultural web full of nuances and history.

In 1950 the cartoon strip Hormiga Negra appeared in La Razón, created by Walter Ciocca; then there was a saga about a border fort and the men who inhabited it: Fuerte Argentino, also by Ciocca, was published in the magazine Misterix; for this work, he asked for the contribution of the historian Hugo Portas. Cabo Savino, by Carlos Casalla, was born in 1954 in the newspaper La Razón and it has a historical record, because it has six uninterrupted decades of gallops on a horse, fights with knives and raids of indigenous people, changing the media where it was published. In 1958, the first issue of the magazine Patrulla appeared, with characters such as Cirilo el Argentino, by Rapela. In 1967, Enrique initiates the publishing house Cielosur, with some partners, and his gauchos characters El Huinca and Fabián Leyes start to lead their respective publications, where there were other cartoon strips, but always with the same subject, like the already mentioned Lanza Seca by Roux and Mapuche by Almendro and Desilio.

RAPELA, THE EDITOR

The publishing house Cielosur gives rise to magazines of several sizes and regularity: some are monthly, others are albums or delivered by installments. In the cartoon strips, there was a segment to the origin of words like pulpería, sangría, ranqueles. Rapela’s passion for expanding the reader’s knowledge leads to the appearance of a special section called Conozcamos lo nuestro [The Gaucho’s Heritage], described as “a singular encyclopedia of rural terminology”, that, in 1977 and in successful subsequent editions, was published in three volumes. In the dialogs of booth cartoons, there is an intention of reflecting the gauchos’ talk, and a lot of their expressions are reproduced there. We could say that both heroes –El Huinca and Fabián Leyes that appeared in Patoruzito and the newspaper La Prensa respectively, during the 1970’s– are archetypical twins of an avenger that, together with their side parties, help others. The companion of the first one is Zenón, and of the second one, Amancio. “For them, that is their life, pampa and sky. Sandy bogs and scrublands. Free like the wind, happy like birds when the day is born”, this can be read in one of the strips. However, sometimes they were also hired as guides for exploration watches around the forts due to their knowledge of the plains and the surroundings.

This entrepreneurial and didactic value joins forces with the aesthetic value, since, if we focus on Rapela’s art, we have to highlight specially the images where he registered the landscape portraying a serene sky with subtle vertical strips; or when he describes the black silhouettes with light white touches that indicate the moonlighting in contrast with the figures. The clothes and the type of fabric are shown in their wrinkles that are represented with skill, as well as the ranchos, the roads, the trees and the stagecoaches are described. It is a restrained, composed, classical drawing, but with greys that not only enrich the composition, but work as ornament. They are fresh drawings, with vigorous strokes and great skill in the use of the brush and the pen. But he outstands specially in the drawing of horses, with excellent images detailing the anatomy of their heads or the gallop of their legs, as well as the saddle and the details of the tack. “He knew how to reflect graphically the immense plains that seems to project to the infinite”, says the writer Germán Cáceres, who was also an ideologist of the gaucho´s culture. He died in Buenos Aires when he was 67 years old, but his mark clearly transcends his short life.

PILAR ALTILIO

Graduated in Arts, UNLP, Posgrado Internacional Gestión y Política en Cultura y Comunicación FLACSO Argentina. Professor in charge of placement in graduate programs on Contemporary Artistic Practices, UNCuyo. Manager and independent curator since 1999. As independent researcher and art critic, she regularly publishes in Revista Ñ de Cultura, ArtNexus, a Colombian magazine, arte-online.net and El Gran Otro.

Sources: Judith Gociol and Diego Rosemberg, La historieta argentina. Una historia. Ed. De la Flor; Carlos G. Landa and Julio César Spota, Trazos fronterizos, at http://www.gazeta-antropologia.es/?p=1477.