Читать книгу Conozcamos lo nuestro - The Gauchos's Heritage - Enrique Rapela - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe gaucho, archetype of the national being

I knew him, I saw him and there he was. Alone, like almost always. By my side, so close that I also believed I was like him. A lie, there was so much I had to learn. How was I to know that someday I could hardly resemble whom? And I was getting closer slowly, afraid of not being cautious. Because, sometimes, the boldness makes some mistakes, like someone who chews bitter grass without knowing that a Gaucho have already done that.

The gaucho is who did everything in this Argentine land. The gaucho, the only archetype of the national being. The gaucho, who left us the nouns gauchaje and gauchada, the first one denoting a group of people; the second one, the “help” coming from those who always give without worrying for anything else.

Sometimes I insist on the fact that being a gaucho is not only to know how to lasso an animal, wear boots, wear a rastra, wear everyday alpargatas and saddle a horse…, it is rather a feeling, that thing of substituting and not asking anything.

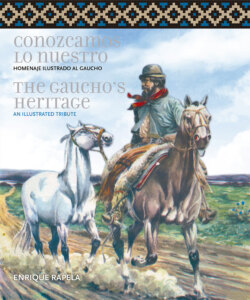

Before defining a gaucho, determining what are, for us, their luxuries, customs and habits, it is really important to talk about Enrique Rapela’s work. He goes from an estancia to an esquinero [corner post in a fence]. From a mill to a wagon. From an extended wire fence to the matera [gathering place for countrymen]. He paints for us the lasso on the left side of the rump, the hobble, the tack up to the encimera [piece of the tack that goes over the rest]. That is what he draws with passion, a style without another option.

ENRIQUE RAPELA, THE MAN WHO TAUGHT US ALL

Enrique was one of those guys who taught us how to draw our stuff. For people of my age, he was the nib, the draftsman, the painter, the scriptwriter and the impressionist of the school of the Argentine gaucho painting; he was one of those writers and illustrators we followed day after day in magazines like Tony and cartoons in newspapers (La Razón).

He was one of the creators of the gaucho’s cartoon; of course, he was a self-taught person because there was not a school for that, but he won, as other costumbrist painters, treating every day the gaucho topic with full knowledge of tradition and history. Aptitude, countryside education, accuracy and dedication turned him into a referent for “The Gaucho’s Heritage”.

His stories, cartoons —called comics today— show all these characteristics. For example, “Cirilo el Audaz”, “Cirilo el Argentino”, “El Huinca” and “Fabián Leyes”. He also had historical evocations of our songs, armies, battles, soldiers’ uniforms. The reason for this was that, since he was a child, in the estancia La Carolina (Roque Pérez), he grabbed the air, the history and its gauchos, always legendary.

He brought himself, as his Cirilo el Audaz, to the technics of watercolor with a strong masculine tone, without abandoning the colors of his homeland. “It will continue…” said Cirilo’s cartoon in La Razón and, in some way, he copied Hernández and the adventures of our main poem: El gaucho Martín Fierro.

Drawing and text. Text and drawing. The artist becomes a scriptwriter, a draftsman and almost a chronicler. In short, he narrates everything.

The synthesis, just one: the gaucho.

ALL THIS IS TRADITION

Tradition is not a melancholic memory of the past, it is a permanent, endless process… and that is the reason why human beings are building today tomorrow’s tradition. Our race was born from a very old race and very new land. So, when the Damascene floor (due to Damascene iron) was splashed with red, our original being —the gaucho— was born.

Maybe we still have to remember this, but our ancestors are none other than Spaniards and indigenous people. Thus, the Creole was born, that is, the gaucho: a man from the land and mainly a soldier in the Campaign of the Desert, with the Colorados del Monte, with the Infernales of Güemes and, essentially, the Grenadiers of San Martín.

And that’s true: the gaucho was our first soldier. There were no tough guys to accompany the militia, and Juan Manuel de Rosas took advantage of his gauchos to advance into the Southern frontier, as well as Julio Argentino Roca. Maybe, this happened after the great Martín Miguel de Güemes and, above all, the greatest among the great, the general who trained them in Plumerillo to cross over the Andes: the Great Captain, José de San Marín.

That’s the reason why we say that the gaucho is a fusion between land and man. The blood, always present. Spilled, erect, scarlet, dark, omnipresent. The land: recovering the end as so many times, raising its spike to harvest, the cattle to cut and the sheep to graze.

If you think that traditions or the gaucho are things from the past, we are going to explain that it is not true and why!: the gauchada is not forgotten. Our countrymen are still living with their luxuries, their customs and their habits.

THE GAUCHO, LUXURIES AND HABITS

The gaucho still has today his “luxuries and habits”. I am going to tell you about this misunderstanding, that thing about the gaucho being “vago y mal entretenido” (lazy and full of bad habits). The gauchos were never lazy, they were “vagos” just in the sense of roaming, wandering, being fee. The bad habits have to do with gaming, alcohol and some gambling for fun. They were the people for the war, the branding, the hard work, the forge, the land, the taming, the wife, the horse, the Pampas, the lagoon and the mountain. They are our countrymen, a scattering of different colors, tastes, and folklore. They are the good taste at the party, in the dance, in food and in life.

Once they asked me if one is different from the other and I said without hesitation that they are. It is not the same a man from the plains, the steppe, the mountain, the hill, the puna, the river, the lagoon, etc. How are they going to eat the same food near the river or in the Pampas; to sing the same songs to the plains or to the mountains? It is not the same to quietly recite a poem or shout. How the man of the canoe, the man from the quebracho in Chaco or the man from the Southern cold weather is going to be dress? It is not the same to find meat of gray brocket, river tiger, yacaré’s tails, lizas, armadillos or any fish from Patagonia, salted and that is okay. Or raising lamb next to the best meat: beef. Hens, ducks and chickens, whatever is in the frying pan. Every animal that walks ends up cooked, and also the marinade vizcacha.

That’s why we keep talking about the countryside, that is, the only land of our countrymen. And, if we refer to their tradition, we come back to their customs and habits.

It is impossible that a gaucho from the mountain wears the same clothes as one from the Pampas. The colors are different, the weather too. They need to fight different troubles. And, in the North, they moved with the aplomb of the sun, with sandals and sweat. In the Mesopotamia, with leggings, and, in the Pampas, with leather boots. Lower neckerchief in Corrientes; higher, in the Pampas. Large brim hat in Cuyo, smaller brim in Buenos Aires and, very proudly, the chambergo, always prominent and quiet in San Antonio de Areco.

If they do not dress the same, it is because of the large country, and they do not saddle the same way either, in this remote land. How am I not going to put a tack with cushions in the plains of the Pampas, or a duck tail tack there where the cueca orders it? Saddle trees in the North or a malvinera saddle and those clear fields, where there is no music. An apron that does not exist anymore, luxury and perico ligero. A brown and neat sheep cushion, under the eaves shade. A Pampa poncho rolled up on the rump of the overo and the lasso, as always, on the left side.

MUSIC AND LYRICS

So, as we talk about the pot, the fire, the wind, the mud or the pan, we can also talk about the ways of saying, because we do not feel the same when there are lyrics, geography and a feeling. How is somebody from Misiones going to sing, modulate and compose verses? And someone from the mountains, or the steppe or the plains? If one looks at the river far away, the other at the blue sea, the forest in the next field, the endless plains, the mountains, which sometimes could be the Andes.

And there the poetry, the singing and the melody: cueca, ranchera, milonga, chamamé, polka, chacarera, tonada, chamarrita, cifra, a paso doble, a cielito, another infiernito, the gaucho sings another thing and slowly composes verses.

The Virgin Mother is a constant in the gaucho’s feeling. Also, his children, the Tata, the boliche, the “vidrio”, the tobacco, the lampost, the charqui, the brine, the mate, the galleta or the branding. Because the gaucho does not rest, he works even on Sundays in a branding, where the lamb rests in the cross shaped grill and the calf´s testicles on the embers, under the grill. Asado, jineteada, carrera cuadrera or any kind of entertainment. Also because he demands it and he knows all that better than anybody.

The animals eat the grass that, fortunately, sometimes grows and, if it is not taken care of, nothing prospers. The countryside is a factory without holidays. It always needs the daily work and a worker on duty.

Just some vices that absurd people ignore. But if we can? Why not a filet, some cards, a stew with rump steak, the loaded taba, plain and stripped bochas, and, if there were some doubts, aguardiente [moonshine] with ruda [ruta].

Anyways, there will always be a good “sayer”, some kind of shepherd who can say that, in any corner, my horse stumbled and fell, that the man who drinks wine cannot call another one a drunk.

So free is the gaucho that he is misunderstood. In some villages, “gauchos’ parades” are promised but the gauchos do not parade, the gauchos pass. Nobody gives them orders, they only respond to themselves with wellness, bonhomie, integrity, good taste, their luxuries and traditions. That is the reason why we talk about the archetype of the national being, of this fusion of land and man.

A SIMPLE GAUCHO’S DAY

In the early morning, a stake is burning at the matera, close to the tamarisks, before he saddles and adjusts the tack. After that, the day and the land, the stubbornness will come, things that, in the countryside, were known long time ago. And then, just a moment to take a nap. A little longer in the field; afternoon, mate and sereno, because, with the dew, it is necessary to start again…

That is the reason why I am telling you that, if the gaucho is neither a myth nor a legend, let us help banish the idea of his fantasy death.

“To the gaucho I carry inside myself, as the custode carries the communion wafer” (Ricardo Güiraldes, that is to say, Don Segundo Sombra).

MARIANO FRANCISCO WULLICH

A journalist for the newspaper La Nación, he toured Argentina for five years for “Chronicles of the Country”. Head of Readers Letters, author of Rincón Gaucho and editorial secretary. He covered the Lebanese war and Antarctic travels: he was on board when the icebreaker Almirante Irízar caught fire. He published the books Nuestra Argentina, El caballo, Don Emilio Solanet and the prologue to Martín Fierro (Sancor).