Читать книгу Conozcamos lo nuestro - The Gauchos's Heritage - Enrique Rapela - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

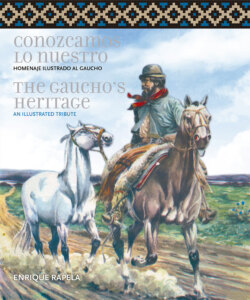

FIRST PART The gaucho

ОглавлениеThe gaucho, the man who inhabited our vast fields, was the day laborer of the large estancias, very skilled in the art of mastering and training the horse, that accompanied him in the jobs related to livestock and agriculture.

This character was extremely punished by those men of letters who only considered that something was good if it had French or Saxon roots. The origin of the so called “gaucho” is uncertain, and the essays to explain it are diverse. For instance, Paul Groussac considers plausible and logic that this word was never said, it was not known in the Iberian Peninsula, except for an American transfer. For him, this is one of the few words that did not pass by Spain before being implanted in the New World. Groussac thinks that it comes from the Incan word “guacho”, that means (in a quite derogatory sense) “abandoned, wandering, orphan”. This is a meaning that, in general, we reject.

Don Félix de Azara, wise man sent by the Spaniard government to implement the Treaty of San Ildefonso, marking the limits between Spain and Portugal in their South American possessions, remained from 1781 to 1801 in the different territories of the Río de la Plata, drawing maps, exploring and writing their later famous books. Great observer, he left concepts that we cannot ignore. Azara, referring to the inhabitant of the plains, expresses:

“It is no less admirable the good sense with which practical ‘baqueanos’ lead to the place they are asked to in horizontal fields, without roads, without trees, without any signal or compass, although they are fifty or more leagues away. Besides them, there are in those fields other lineages of people, called more properly GAUCHO or GAUDERIOS”.

The name “gauchos” or “gauderios”, designating, at the beginning, those adventurers of the plains, later on comprised all countrymen devoted, in general, to shepherding.

The gaucho had always a white complexion. His look was more Arabic than Indigenous, as some historians at the service of something that does nothing to do with our origin pretended to make us think. We cannot ignore that the blood of Spanish conquerors was a decisive factor in the ethnological constitution of each group, to deduce, with fixed bases of criteria, the ulterior importance, their activities and the influence they had in the individual and group character.

There are many authors that have wanted to see, in the origin of our gaucho, the Spanish Moor. They back this theory on the resemblance they see in their clothing and the similarity of the elements they used. They saw in the poncho the Berbers’ gown, and the chiripá reminded them the wide breeches of the natives of Mediterranean Spain. The wide belt decorated with coins, the colored and broad neckerchiefs and the weapons, as well as the sash that hold the chiripá seemed to them of Eastern origin; the long facones (both the tool and the weapon); the huge beards and the wide embroidered breeches led them to fall in that mistake.

Obviously all that has been mentioned gives our gaucho a great resemblance to the Mohammedam peoples of the East. The distinctive features of the clothes, the physical type, the way of riding, and many words of Arabic origin, commonly used in the Pampas, such as “jagüel” [well], for instance, have led to the mistake of taking as a possible origin a migration of Spanish Moors to this part of the world. This has to be dismissed because the Moors didn’t come to America at that time. But Moorish Spaniard did come, the Andalusian horsemen, those children of Moors that, when they saw themselves in these vast plains, felt a reawakening of the slept heritage of their grandparents, those bohemians dreamers that abandoned the huge Arabic deserts to conquer almost all Spain at spear point, under the fruitful reign of Isabella of Castile in that 1492, leaving with an indelible force, as their heritage, their ancient art and culture, that then began to decline.

The first generations born here preserved the bellicose nature of Juan de Garay and Pedro de Mendoza’s expeditionaries, who fought against the brave and fierce indigenous people when they knew how to master the horse. From this fight the “gaucho” was born: elegant and valiant horseman that maintained, within his intellectual rusticity, the integrity of his character and the nobility of his heart. The gaucho was an honest and brave up to recklessness horseman. His wild courage turn him into a great warrior, agent of the American emancipation. Hospitable, they give food and refuge to the traveler without asking who he is or where he goes.

The gaucho only got from the indigenous people his astuteness, his moderation when it was necessary, his knowledge of the land and his skills to use primitive weapons. The most common thing was that he led his horse to some rancho de cristianos when he needed a woman. The hazards of the war or his needs led him to join an indigenous woman. Through time, this lonely man from the pampas, who became isolated keeping himself between civilization and barbarism, refused to acknowledge the authority of the Municipal Council and even less that of the cacique of the toldería.

Reticent in general to any kind of organization, he was individualistic almost until the last consequences; we can say that he lived in a community and with other gauchos in festive days. He was used through centuries to isolation and he only counted with his own effort to cope with his then easy existence. His skills in hunting wild animals in the huge green deserts was enough to live and earn money. He was generous and disinterested, he did not care too much about money; he did not care a lot about the fact that “after a day of abundance, a week of scarcity” followed: “day of a lot, eve of nothing”.

The gauchos, because of some imported philosophical trends and extra national interests, were orphans of any society, some were abandoned by “civilization”; today, when we have more subtleties dictated by the experience, more or less the same is happening. But the gaucho that watered with his blood the long journey to the independence of many American nations, was abused by the “historians” when, after the independence, the civil confrontations started in the country and he took part in public life and received less than he deserved when he gave to history “tremendous [heroes] of a wild glory”, skilled way of reducing the value of his intervention.

The personality of this fabulous ancestor was so overwhelming that, even his biggest detractors, due to education or foreign influence, could not help feeling attracted to this “outcast of civilization”. Daireaux was one of the people who finally paid tribute to him. Domingo F. Sarmiento, who did not hesitate to advice “… and do not economize in gauchos’ blood”, also pays his tribute in Civilización y barbarie, when he recognizes in the baqueano (a gaucho like many) an extraordinary being with keen sense of observation and great intelligence to draw conclusions from details that went completely unnoticed to the “civilized and educated” man.

Another gaucho, the great Facundo Quiroga, target of the attack of all the thinkers influenced by the European culture of that time, and their followers today, could not be less than compared to a legendary hero when he was considered “the hairy Achilles of the gauchos’ Iliad”.

The influenced literature of the time exaggerated when it had to judge the gaucho; it labeled him as a “gaucho malo” [bad gaucho], an individualistic man who, with a great libertarian spirit, refused to serve the interests of the “educated people”. Frequently, he was forced to defend his freedom with weapons and became a fugitive; if he did not die in the endeavor, he ended up in the frontier serving under a very strict regime. There he fought in poverty to contain the indigenous people, taking care of, and defending the interests of his condemning judges, without any future but to die in misery.

In this essay, I will try to remember the afflicted gaucho, showing him in his environment, with the pressure of approaching the truth about the elements with which he developed his existence, his traditions, the superstitions and some “laws” that ruled his life and relationships.